Candidate and party list registration through voter signature collection

Balabanova O.V., Bolshakov I.V., Buzin A.Yu., Vorobyov N.I., Grezev A.V., Evstifeev R.V., Kiselyov K.V., Klyga A.A., Kovin V.S., Kryzhov S.B., Molchanov O.A., Nesterov D.V., Pokrovskaya O.L., Raczynski S.Z., Rybin A.V., Titov M.V., Fedin Ye.V., Khudolei D.M.

Abstract

Election and electoral law experts discuss the issues of candidate and party list registration through voter signature collection. The discussion focuses on the rules for collecting signatures and the verification procedure (including procedures involving handwriting experts), the required number of collected signatures, and the allowed percentage of rejected signatures. Opinions include the need to “change the philosophy” of candidate and candidate list registration based on voter signatures in such a way that it prioritizes ensuring citizens' electoral rights over bureaucratic procedures. Discussion proceedings come to the conclusion that reform in this area can only be effective if it is done in a comprehensive manner.

Editor's note

Voter signature-based registration was introduced in Russia in 1991 for the Russian presidential and Moscow mayoral elections. From 1993 to 1999, voter signatures were the only grounds for the candidate and party list registration [13: 257-258, 316]. Issues revealed themselves even at that time. For example, this is what A.A. Veshnyakov, then Secretary of the CEC of Russia, noted in 1997: "Practice has shown that such an approach without due responsibility of persons collecting voters' signatures, without an effective mechanism of verification of signature sheets submitted to election commissions has led to criminalization of this process, mass falsification of signature sheets" [34: 72]. On the other hand, there was arbitrariness in the verification of signature lists, which led to many popular candidates being denied registration [28: 67, 265-266, 275, 278].

These issues led to the introduction of election deposit-based registration of candidates and candidate lists in 1999, which was abolished in 2009. Since 2004, candidates and lists of the strongest parties have been registered without signatures and deposit [4: 123-125; 13: 340-341, 534, 564].

Nevertheless, voter signature collection remains in place. It is required for self-nominees and representatives of "small" parties. At the same time, we often see representatives of the "party of power" running as self-nominees when they wish to distance themselves from United Russia. For example, such was the case in the 2019 Moscow City Duma election. United Russia did not nominate any candidates, and all candidates affiliated with this party ran as self-nominees. In total, 103 candidates (out of 292) who needed to collect signatures were registered in those elections through voter signatures [35]. Self-nomination has been used repeatedly (in 2004, 2018, and 2024) in presidential election by Vladimir Putin, and in Moscow mayoral election by Sergei Sobyanin (in 2013 and 2018). In the 2018 presidential election, six candidates out of eight were registered through voter signatures. However, in the 2024 presidential election, Vladimir Putin was the only one to get registered using voter signatures. In the 2016 and 2021 State Duma elections, no party list was registered using voter signatures, and the number of single-seat candidates registered on this basis was extremely small (23 and 11, respectively) [12: 254, 383].

At the same time, there is a certain paradox that emerges quite often. On the one hand, little-known candidates quite easily get registered using voter signatures to receive fewer votes than the number of signatures they collect. On the other hand, candidates whose significant voter support is evidenced either by the results of other elections or by sociological surveys fail to pass the signature filter. The same applies to parties [3: 706-707; 15; 17: 490-491; 16; 28: 66-67, 265; 35].

As early as in 1998, the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation made a legal statement, according to which “in the interests of voters, the legislator has the right to provide special preconditions in order to exclude from the electoral process those participants who do not have sufficient support of voters" [27]. It was later reiterated numerous times in other Court documents. As a result, the meaning of the signature filter as interpreted by the Constitutional Court is to exclude weak candidates from the electoral process. Therefore, the aforementioned paradox indicates that the signature filter does not (or does not always) fulfill this constitutionally significant function.

The reasons for this phenomenon seem to lie in the unsuccessful provisions of the law that regulate both the procedure for collecting voter signatures and the rules for their verification. These norms have long been criticized [4: 137-138; 15; 17: 490-491; 16; 28: 265-266; 32: 109-113], and the critics include members of election commissions [6; 8; 22]. Moreover, there is a certain practice of verifying signature sheets that does not fully comply with the law. In particular, the practice of recognizing signatures as inauthentic or invalid on the basis of handwriting examination raises serious doubts [3: 332-333, 487-489, 699-708; 8; 17: 491; 16; 28: 275; 35].

There were several occasions when various measures to remedy the situation were suggested as well. One of such suggestions has to do with the restoration of election deposit [4: 141; 7; 10: 97; 18: 132-135; 22; 25]. There is also a radical idea of a complete elimination of signature collection as a practice [32: 113]. Other suggestions include changing the way signatures are collected and verified. For example, A.A.Veshnyakov proposed to switch to collecting signatures in specially designated locations [34: 72]. This idea was sufficiently elaborated in the draft Electoral Code of 2011 [10: 98-99], but not all experts support it [18: 150-153]. Later, the idea of collecting signatures through electronic services (e.g., through the Gosuslugi portal) emerged [18: 150-153; 19; 25]. This idea was partially implemented in the Federal Law of 23 May 2020 No. 154-FZ, but experts say the implementation was not quite successful [12: 370]. There were quite a few suggestions to change the rules for verifying signature lists [10: 99-100; 18: 154-159; 25]. There was also a suggestion to reduce the number of signatures to be collected [18: 154-159; 22; 25].

However, the legislators not only rejected most of the suggestions, but decided to further complicate the procedure for collecting signatures and toughen the rules for verifying signature sheets in Federal Law No. 154-FZ of 23 May 2020 [12: 370-371]. Consequently, the discussion of the issues of candidate and party list registration through voter signatures remains relevant.

The editorial board invited experts to answer 11 questions related to the collection and verification of voter signatures. Eighteen experts offered their responses. These experts include four candidates of legal sciences, two former chairpersons of election commissions of constituent entities of the Russian Federation and three former members of such commissions, four former members of the Scientific and Expert Council of the CEC of Russia.

Question 1. What is the purpose of collecting voter signatures from the point of view of the realization of citizens' electoral rights, and is it being achieved?

Yevgeny V. Fedin

In my opinion, the purpose of collecting signatures from the point of view of the realization of citizens' electoral rights is to identify candidates with the maximum level of voter support, so that the set of candidates on the ballot does not create difficulties for voters to examine, determine and declare their preference by expressing their will.

Andrei Yu. Buzin

This is a perfectly acceptable and common way of supporting the nomination of candidates around the world. It can serve as an indicator of support and to some extent replaces the nomination of a candidate by a group of voters. In small local elections, nomination by an assembly of voters may replace signature collection.

Mikhail V. Titov

It seems that signature collection and its effectiveness may serve as some indicator of voter support for a candidate. However, this purpose can only be achieved if the implementation procedure is organized and controlled properly.

Olga V. Balabanova

The purpose is to prove support for a candidate/party among a significant part of the population. This was originally an added guarantee of nomination for candidates with limited budgets who were unable or unwilling to run from a parliamentary party and did not have the funds to pay the deposit. The procedure turned into a roadblock after the deposit was abolished and due to certain "peculiarities" of law enforcement. The purpose of realization of citizens' electoral rights is not achieved.

Aleksandr V. Grezev

Signature collection, in the broad sense of the term, is quite a routine condition for registration of a candidate or party in elections at various levels. Purposes may vary depending on the level. In local elections, this is evidence of minimum support for a candidate to get on the ballot. In federal campaigns, a certain threshold can be used to filter out outright hollow participants with no endorsements, spoiler candidates, etc.

Dmitry M. Khudolei

The sole purpose of signature collection should be to identify candidates who could potentially represent citizens in a specific (sole or collegial) public government body. Consequently, hollow candidates and those candidates who abuse their rights (technical, fake, etc.) should not be allowed to run. That is, in theory. In practice, this purpose is unlikely to be achieved. Parties with privileges often nominate technical and shill candidates. On the opposite end of things, certain earnest candidates fail to pass the signature collection procedure in elections at both federal, regional and local levels of public government.

Oleg A. Molchanov

Can voter signature collection serve as an indicator of voter support for a candidate? Yes, but the will of a verified voter can be confirmed in other ways. For example, at the moment there exists an established interaction between the Gosuslugi system and systemically important banks (it is banks that collect biometric data of citizens, which then become the basis for identity verification by various public and private bodies). That is, signature collection in support of nomination can also be carried out with the help of voter identification by a large bank, if the voter is a client of this bank and the bank is responsible for verifying the voter's identity (including with the help of biometric data).

Stanislaw Z. Raczynski

Collecting signatures in support of candidate nomination is theoretically a type of barrier designed to prevent needless ballot bloating. Among the many options, this is the worst, as its quality administration by the electoral system is orders of magnitude more costly than other known barriers, not to mention the fact that the administrative procedure itself is not resistant to abuse by both candidates and bodies of state power.

I would like to emphasize that the above applies to traditional signature collection; electronic signature collection is devoid of these disadvantages (although it has its own, quite different ones). It seems that the difference between these two types of signature collection is so great that it makes no sense to consider them together at all.

Sergei B. Kryzhov

The purpose of collecting signatures is to make it difficult to realize the right to candidate nomination or self-nomination by filtering through the institution of signature collection. On the one hand, signatures act as a simplified equivalent of recommending this particular candidate and nominating him/her by a meeting of citizens. On the other hand, signatures act as a simple expression of consent by voters to the participation of a candidate in the election campaign among others, with the right of a voter to sign for two or more candidates. The difficulty has to be high enough to ensure that every worthy candidate is able to overcome it, but not excessively so that some worthy candidates are unable to register. This, in fact, is a matter of skill for the legislator who wishes to maximize the exercise of citizens' electoral rights.

This purpose is achieved in the lowest level election, that is, to the local government, when voters presumably know each other and the candidate. At a scale of over 2,000-5,000 voters in a constituency, modern technology makes it possible to collect signatures for any candidate.

Artyom A. Klyga

For all its shortcomings, signature collection may serve as an indicator of voter support for a candidate. But this is an exception rather than a general rule (e.g., Boris Nadezhdin's campaign in the 2024 presidential election).

Most often, the required number of signatures on signature lists is collected through the competent work of the election headquarters or candidates themselves. A nominated candidate collecting signatures may not have any recognizability at the nomination stage, but thanks to his or her headquarters or personal activism, he or she can reach voters who may have had no idea that there was an election in their constituency.

This can often be seen in municipal or regional campaigns of self-nominated candidates. Although there is an example of successful signature collection at the federal level as well (the campaign of Anastasiya A. Bryukhanova in the 2021 State Duma election).

Nikolai I. Vorobyov

The current legislative regulation of the procedure for collecting and verifying signatures and making a subsequent decision on the registration (or rejection of registration) of a candidate (or candidate list) actually does not meet the constitutional standard of "free democratic elections" (Article 3 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation). In fact, what we have in the current legislation is a permit-based rather than a free notice-based procedure for election admission (like the legislation on assemblies).

A free election implies free nomination and running of candidates and parties. So what do we have instead? Our legislation allows absolutely arbitrary bureaucratic filtering of candidates, denying registration to those who are undesirable to the current government. All while elections are inherently supposed to express a real choice between competing candidates and political parties. Candidates and political parties should be freely admitted to elections and freely participate in election campaigns.

The discriminatory procedure established by the current legislation for admission to elections through signature collection(not for all candidates and not for all parties, mind you) is only a minor, private indicator of support for a candidate during the election preparation. And nothing else! It's not indicative of anything else.

Konstantin V. Kiselyov

The purposes of signature collection in hypothetical ideal circumstances and the current circumstances in Russia are two absolute opposites. In ideal circumstances, collecting signatures has implications for the entire political body politic on the one hand, while on the other hand it can be beneficial for candidates themselves.

First, collecting signatures is a way to filter out the "crazies," spoilers, etc., i.e., those who, by getting on the ballot, will not contribute to the realization of electoral rights, but, on the contrary, will hinder such realization. A list of a hundred candidates, where 80+ percent are ballast, is always worse than a list of 5, 10 or 20 who will actually compete for votes, present their programs, etc. Second, collecting signatures is a way for candidates to clarify for themselves whether voters are ready to support them, as well as a way to clarify their stances on extremely specific issues of a specific territory. Third, collecting signatures has technological implications for candidates themselves. For example, it can be one way to build a support group for a candidate.

In this respect, signature collection may certainly be an indicator of voter support for a candidate. Yet we need to keep in mind that collecting signatures is not the only, much less the best, indicator of this kind.

In Russia's current circumstances, the collection of signatures serves as an administrative barrier first, and as a mechanism for practicing the methods of administrative coercion second.

Olga L. Pokrovskaya

In my opinion, voter signature collection in support of the nomination of a candidate (candidate list) should confirm the organizational capacity of the candidate (electoral association). A correct understanding of the legal acts regulating the signature collection procedure and the ability to properly interpret them in the process of filling out signature sheets and executing the necessary documents for submitting the collected signatures to election commissions requires certain qualities and skills necessary to exercise the powers of deputies and elected officials of state and local government bodies.

However, even a significant number of signatures collected in support of the nomination of a candidate or an electoral association is hardly an indicator of the level of public support. Especially since the degree of public support for a candidate or an electoral association may change significantly during the election campaign.

For example, in the 2021 St. Petersburg Legislative Assembly election, The Russian Party of Freedom and Justice submitted 20,497 signatures of voters to the St. Petersburg Election Commission in support of the nomination of the candidate list, which was subsequently registered. On election day, however, this party received only a little over than that — 33,452 electoral votes (out of the possible 3,871,548).

Ivan V. Bolshakov

The only purpose of collecting voter signatures is to filter out random people (regular people, dilettantes) and not to turn the electoral process and the institution of representation into a Hyde Park or an over-exaggerated Agora. Signature collection does not measure a candidate's support per se, but serves as an indicator that the candidate represents the voters, not just himself or herself. However, signature collection rules should not lead to inequality or become a means of limiting competition between real actors in the political process, as is the case in authoritarian countries like Russia and Belarus.

Reasonable restrictions on passive suffrage are necessary to avoid breeding a multitude of electoral participants who receive a negligible number of votes by taking them away from others. At the same time, not only signature collection, but also the nomination procedure from political parties or registered associations of voters can fulfill this function. The complete absence of entry barriers, however, generates unfair voting outcomes, distorts voters' true preferences, and reduces the effectiveness of representation: the more participants in an election, the fewer voters the winners ultimately represent.

Of course, random candidates overestimating their capabilities can be found in any country, but the fact that this is a blooming phenomenon is rather a characteristic of the "growth disease" of democratic institutions. Under stable rules of the electoral game and consolidation of the party system (the system of moderate pluralism seems to be the most favorable in this case — see the classification of G. Sartori [29]), the need for specially established entry barriers will be reduced, and the number of candidates will be determined not by election commissions, but by competitive positions and agreements between election participants.

Roman V. Evstifeev

Voter signatures collected in support of the nomination of a candidate may be an indicator of support for the nomination of a candidate. But one should be aware that there can be many such forms of support (only in theory in some countries). From mass and non-mass rallies, assemblies and marches to one-person protests; from various kinds of public street representations to public political statements (again, in some countries this is possible only in theory). And also various forms of expressing support using information technology, on the Internet, in messengers, etc.

The main advantage of collecting signatures in support of candidate nomination is the convenient control state bodies can exercise over the process and the result (opportunities to influence the process and the result), convenience of counting, accounting, evaluation and rejection of signatures (recognizing them as inauthentic, invalid, etc.).

In essence, a signature is an expression of the will of a person, that is, the shape that the will takes and which is recognized as such under the law of the land; that is, the will is primary and must be considered as such when questions and issues arise with its tangible expression in the form of a signature.

However, this is by no means always the case. Russian legislation and law enforcement make it possible to recognize the expression of will in the form of a signature as more important evidence than the will itself. This approach prioritizes form over substance, i.e., the fact of expressed will. This could be called formalism, but in fact it often devolves into political tomfoolery.

Vitalii S. Kovin

From the perspective of the political system, signature collection is a way of filtering candidates, weeding out the "weak" and/or "unacceptable" and letting in the "strong" and "acceptable". What separates "weak" from "strong," "acceptable" from "unacceptable" depends on the characteristics of the system even more than on the candidates themselves. The more competitive and democratic the system is, the more significant for overcoming the signature filter are the electorable "strength" and "weakness" of a candidate; the more rigid it is, the more important is the "acceptability" or "unacceptability" of a candidate. For "weak" candidates who, within the rigid system, fulfill the role of covering the main candidates ("technicians", "spoilers", "sparring partners", etc.), there will be no problem in passing this threshold, regardless of how it will be organized: through the collection of signatures on paper or in some other way.

From a candidate's perspective, signature collection is just a way to get on the ballot. The purposes of getting on the ballot do not always imply the desire to get elected, it may be a technical cover for the primary candidate, and the desire to earn political and material capital, to get fame and so on.

From the voter's perspective, signature collection is a way to show approval of a politician who has expressed a desire to compete for elected office. It is also a way to publicly demonstrate their desire to see the candidate on the list, as well as to confirm that this is not only a personal desire of the politician himself, but also of a certain significant set of voters (ideological, value, ethnic, situational, etc.) united by ideas about a desirable and worthy candidate for power. In other words, to create a condition for themselves to campaign and vote for the candidate the voter "prefers". The existing format of signature collection does not meet this purpose.

In the case of opposition politicians, signature collection has turned into a political campaign to overcome the political and bureaucratic barrier set up by the authorities. For candidates whose participation in the elections is considered useful by the authorities, it has become a strictly procedural preparation of signature sheets. In the current format, collected signatures, like many other tools, may either serve as an indicator of electoral support or mean nothing.

Aleksei V. Rybin

There are two approaches to understanding the procedure of collecting signatures in support of candidate nomination: 1) liberal: signatures are an indicator of the minimum necessary support for a candidate to be allowed on the ballot; 2) restrictive: signatures are a tool to keep candidates off the ballot in order to reduce their number and simplify the choice among the remaining candidates.

The U.S. example shows both restrictive and liberal approaches. In Georgia, an independent candidate has to collect 5% of the signatures from the number of voters in the state's last gubernatorial election to get on the ballot for the U.S. House of Representatives — it amounts to 72,336 signatures in 2024. In North Carolina — 10,000 signatures. These are examples of a restrictive approach. Tennessee and Hawaii are extremely liberal requiring 25 signatures, California is similarly liberal at 40 to 60, and Rhode Island is moderately liberal at 500 [30].

The authors of the American textbook of election law refer to signature collection as a process characterized by the U.S. Supreme Court as a "many-fewer-few" process, i.e. reducing the list of candidates to a reasonable number [9]. In the case of López Torres [24], the U.S. Supreme Court found the requirements of the Law of New York (a petition with 500 signatures collected within 37 days before the primary in order to be placed on the ballot for the primary) to be reasonable, and added that states can require people to demonstrate "a significant amount of support" before giving them access to the general election ballot, lest they become ungovernable. In Jenness v. Fortson [11] the Court upheld the requirement of petition signatures for inclusion on the general election ballot of 5% of eligible voters, and in Munro v. Socialist Workers Party [23] the Court supported 1% signature petition requirement in the state primary. As a result, the U.S. Supreme Court finds it unnecessary to distinguish between the restrictive and liberal approaches and believes that either approach is one that a state may choose at the will of the legislature.

In Russia, we also see two approaches to signature collection: liberal in municipal elections (see Clauses 1, 2 of Article 37 of Federal Law No. 67-FZ of 12 June 2002 "On Basic Guarantees of Electoral Rights and the Right to Participate in Referendums of Citizens of Russian Federation" dated 12.06.2002); restrictive in sub-federal and federal elections (see paras. 1.1, 1.2 of Article 37 of the said law). However, in Russia's current political circumstances, the collection of signatures at all levels should be seen as an instrument of administrative screening of candidates who, for one reason or another, the concerned administration does not want to see elected.

Question 2. Should the signature collection procedure be subjected to substantial changes?

Andrei Yu. Buzin

The signature collection procedure does not require substantial changes. What should be retained are bans on collecting signatures at places of work and study. However, improvements are possible, such as collection via Gosuslugi or at supermarkets.

Olga V. Balabanova

No, the procedure is fine. It is the law is poorly enforced. Signature collection using digital platforms is provided for, but is limited by the desire of the election commission and the 50% threshold (there is no logic to this). I believe digital signature collection is a good idea. Signature collection is designated locations, not so much.

Mikhail V. Titov

It is certainly more appropriate for voters to come to the collectors rather than the collectors to the voters. Signature collection should be conducted in designated locations under the supervision of election commissions.

Nikolai I. Vorobyov

I believe signature collection procedure is in need of legal changes. The number of signatures required should be reduced dramatically. And the signatures themselves should be collected in specially designated locations (premises) and under the control of election commissions that will register candidates.

Aleksandr V. Grezev

In elections at any level and in all regions, candidates and parties should be allowed to collect up to 100% of digital signatures, i.e. to completely abandon the usual signature sheets. Traditional collection should be allowed only if the candidates themselves, for various reasons, are unable or unwilling to collect digital signatures. In this case signatures will be added to digital ones or be on paper only. At the same time, candidates should determine the format of signature collection themselves.

Konstantin V. Kiselyov

Substantial changes in procedure are long overdue. Up to and including abolishing and replacing signature collection with election deposit, for instance. The ideology of the changes is also clear: 1) reducing the number of required signatures; 2) expanding the voter's choices when signing (in person at home or in any other arbitrary or specially designated location, in election commissions, at a notary, via Gosuslugi, etc.). Establishing only one/two possible choices (e.g., in or under the supervision of election commissions) would clearly become nothing more than an added administrative filter.

Sergei B. Kryzhov

I consider the collection of signatures through digital services just as promising as remote electronic voting (REV), but on the condition that the voter is left with a legally valid digitally certified result of his/her signature for a candidate or ballot, which can later be used for a parallel count or recount. Until this is ensured, digital services are not to be trusted.

I agree with the idea of collecting signatures in election commissions under the control of the candidate (party), with the responsibility for the validity and reliability of signatures placed on the commissions, with a multiple reduction in the number of signatures required.

Ivan V. Bolshakov

The rules for collecting signatures should be as simple and convenient as possible, so the first thing that should be done is to abolish redundant requirements for signature sheets, their completion and certification. The payment for the production of signature sheets from the campaign depository should no longer be required, which would allow signature collection to begin immediately after the election commission is informed of the nomination, without waiting for the opening of a special campaign depository. It is also necessary to abolish the notarization of information about the persons who collected signatures. Voters should be given back the right to handwrite only the signature itself and the date of the signature; collectors may fill in the rest of the voter information.

Roman V. Evstifeev

In my opinion, the signature collection procedure in Russia should either be abandoned altogether or seriously modified by enclosing, for example, the transfer of an insignificant amount of money (say, 10 to 50 rubles) from the voter's personal account or bank card to the signature (this is a fairly common practice when using some commercial services, which refund the amount to the client after verification). If the candidate is registered, the amount may be refunded.

Since bank data is dispersed and government agencies have very limited access to it, it seems to be a much more reliable evidence of the will of citizens than physical signatures or even data from the Gosuslugi.

Stanislaw Z. Raczynski

As I wrote in my response to the previous question, digital signature collection is, in my opinion, a different form of electoral threshold; it should be discussed as an alternative to traditional colelction, on par with election deposit, etc.

Collecting signatures through election commissions reduces the risks of abuse (but you still cannot verify signatures for an administrative candidate), but it makes the work of candidates much more difficult: it is much harder to convince a voter to visit the commission's premises than to collect signatures on the street. We should also take into account the fact that we're not talking about election day, and no one is going to ask the commissions to report the turnout. As a result, voters will receive the full range of "low-pressure service", so to speak: the doors might be locked, work might be slow and the members might even be downright rude, which will make it even more difficult to collect votes.

Vitalii S. Kovin

There should be a shift from "signature collection" to a public "show of support". This show of support can be expressed in a variety of forms: from the traditional paper or digital signing of some documents (signature sheets, petitions of support, nomination applications) to support expressed in cash (bank transfer to the candidate's fund) or any publicly verifiable form (a statement of support announced in the media and/or sent to the election commission, becoming a member of trusted agents, even a post on a social network with a certain number of followers). The manner and place of showing support should be varied and equitable. These can include candidates' headquarters, election commissions, state services (such as Gosuslugi, MPSC), state banks (Sberbank, VTB), specially created Internet resources such as fundraising and petition platforms, and even state media. Signatures (more precisely, data about the voter) left on different resources are accumulated in the candidate's personal account on the election commission's website.

At the same time, I believe that all lists of signatories should be public so that every citizen could become informed about them (full name, date of birth, place of residence).

Moreover, collecting signature or raising support should be cumulative in nature, meaning it stops when a certain minimum threshold of verified signatures is reached.

Yevgeny V. Fedin

Based on the need to preserve signature collection (which to me is not obvious), it seems appropriate to address the problem of candidates being denied passive suffrage due to mistakes or malevolent actions of others: mistakes by collectors and voters should not lead to a decision to deny registration of a candidate if invalid/inauthentic signatures could not be detected by the candidate when certifying the signatures and if it there is no proof that these mistakes were made at the candidate's instruction.

In view of the decision of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation of December 28, 2021, No. 2962-O [5], the introduction of the need to notarize the information about the persons who collected signatures should be recognized as an unsuccessful innovation, since notarization of this information unduly leads to a candidate being denied passive suffrage.

Signature collection in designated locations under the supervision of election commissions can be a significant change in the procedure only if the signatures collected under the supervision of election commissions are not invalidated due to voter mistakes after the signature collection stops.

Dmitry M. Khudolei

At present, only a few of the nominated candidates who have no party privilege manage to collect signatures without violations. There's no doubt the procedure needs changes. I consider signature collection via Gosuslugi as having the most advantages. Naturally, the voter's account will have to be verified. Generally, I would not rule out the need to require the voter to take a photo (selfie) when engaging in such activity via Gosuslugi.

Overall, signature collection in specially designated locations also seems like an option. But, in my opinion, in this case the signature collector should be a member of the election commission (TEC, for example), which is explicitly prohibited by the current legislation. A number of other issues arise in this case: the TEC premises are unlikely to be the place for signature collection due to legal restriction, and TECs obviously don't have enough personnel to perform such an amount of work (assuming the existing required number of signatures is maintained, of course). Other variants of this new procedure would again result in the signature collector being an outsider (non-professional) with no access to voters' personal information. Therefore, it will also be possible for collected signatures not to be counted for some (often purely formal) reason.

Artyom A. Klyga

Being an opponent of signature collection, I believe that this procedure should either be completely abolished or other procedures should be created along with it to allow a candidate to be registered for the election.

In the context of making signature collection easier and minimizing the errors that can be made during collection, the proposal to collect signatures through online services has merit. Without elaborating on the fact that this system can be used by executive authorities to create obstacles for certain candidates, it is worth noting that it is much easier to convince voters to sign via online services. This helps to avoid a great number of errors that result in invalidation of signatures.

Collecting signatures in specially designated locations, for example, in the premises of election commissions, in my opinion, will only complicate the procedure. It is possible to consider it in a situation if, say, a part of signatures (1/2) will be collected online, and the candidate will have guarantees that the signatures collected in specially designated locations cannot later be recognized as invalid on certain grounds (for example, claims from a handwriting expert).

Oleg A. Molchanov

I support both options (collection of signatures through electronic services and collection of signatures in designated locations under the supervision of election commissions). There are countries that also have a procedure for election commissions to verify the authenticity of support for a particular candidate. The voter must be able to personally report to the permanent election commission, which must verify his/her identity and accept the voter's vote in support of a particular candidate or electoral association. The election commission should issue a document to the voter stating that his/her vote in support of the nomination has been accepted and inform the respective candidate and/or electoral association of this fact. For the purpose of deciding whether to register the candidate, such a vote must be deemed to be pre-verified and may not be deemed inauthentic or invalid. There should be no way for a third party (even with a notarized power of attorney) to perform such an act on behalf of a voter. When the election commission is informed that a citizen with limited mobility wishes to sign in support of nomination at home, members of the election commission will be required to visit him/her (the procedure is similar to voting on election day).

Olga L. Pokrovskaya

The signature collection procedure in support of nomination of a candidate (candidate list) requires significant changes.

First, the number of required voter signatures should be significantly reduced. For instance, a self-nominated candidate for the office of the Governor of St. Petersburg has to collect 2% of voter signatures (as of 1 January 2024 this percentage amounts to 76,339 signatures). This number of signatures along with the proverbial "municipal filter" acts as a barrier. Only "administrative" candidates are able to reach it, which ultimately has a negative impact on voter trust in the elections. Voter signatures collection as a condition for registration of candidates and candidate lists is found in the legislation of many European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Lithuania, etc.), but in most cases the number of required signatures is limited to several hundred [14].

Second, the requirements for completing the signature sheet should be made simple. As of today, the requirements imposed by federal law are redundant. The requirement for voters to handwrite their last, first and patronymic name on the signature sheet is definitely redundant. Not all individuals are capable of writing them neatly and without marks in a small box on the signature sheet.

The elections of the President of the Russian Federation, the Governor of St. Petersburg and deputies to the Legislative Assembly of St. Petersburg require notarization of information on signature collectors and their signatures. As of 1 January 2024, in order to register a candidate list nominated by an electoral association for the elections to the Legislative Assembly of St. Petersburg, it is required to submit to the election commission at least 19,984 signatures of voters, while the required number of signatures for the registration of a self-nominated candidate for Governor of St. Petersburg amounts to 76,339. In order to collect that many signatures, it is necessary to involve hundreds of collectors whose signatures and data must be notarized. Moreover, this procedure actually excludes the participation of proactive supporters of candidates and political parties, who are ready to collect and submit to the election headquarters only a few signatures, usually their own and family members'. Such citizens often refuse to go to a notary public. And not every notary public provides such services.

The collection of signatures through digital services should be more widely used in elections. It is very important to bring back the election deposit as an alternative to signature collection into the law and electoral practice.

Aleksei V. Rybin

I believe that the issue of collecting signatures is not the complexity of the procedure or exaggerated requirements on the number of signatures, but the so-called administrative resource, i.e. the will of the administration dominating over the will of the voters as to which candidates it wants to see elected to the corresponding public elected bodies. In light of this, I see no need to change anything about the signature collection procedure at this time.

However, in future, when and if the "election administration" issue is resolved, I would lean towards choosing a liberal or restrictive approach when constructing a signature collection model. Both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. The liberal one makes it easier to get a citizen running for elected office on the ballot, but the ballot runs the risk of becoming "bloated." In the words of the U.S. Supreme Court, access to ballots in elections should not be too easy lest they become unmanageable. So what seems reasonable to me is a moderately restrictive approach, where a candidate is subject to reasonably feasible signature collection requirements, but not overly relaxed in the number of signatures and the signature collection procedure.

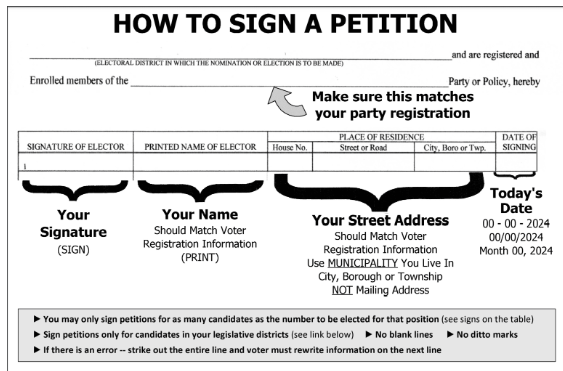

Considering this I would make the signature sheet somewhat simpler by excluding the date (year) of birth and the voter's passport number, as well as shortening the "header" and the certification part. For example, the signature sheet form for Pennsylvania elections [33] could be used as an example.

The form of the subscription list in Pennsylvania

I would suggest abandoning the notarization of the list of collectors, as practice shows that engaging a notary public makes the candidate's task more difficult rather than easier (the candidate actually has to control the notary public and be held liable for their mistakes, which is absurd).

I would introduce a longer collection period and eliminate the restriction on follow-up signatures after they have been submitted to the commission. Such a procedure is in place, for example, in U.S. presidential elections (see, case in the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Nader v. Keith 385 F.3D 729 [9: 499–506]).

Question 3. What is your opinion on the practice of collecting voter signatures via Gosuslugi?

Mikhail V. Titov

I believe that this question can only be answered after a careful professional analysis of the existing practice.

Aleksandr V. Grezev

The practice is extremely limited and has been deliberately neglected in terms of development. I have never encountered it in my personal practice or in my region.

Nikolai I. Vorobyov

The option to collect signatures through Gosuslugi was introduced in 2020. Since then, although there has emerged a certain amount of experience, none of it has been seriously and substantively analyzed. Therefore, its assessment would clearly be premature and unproductive.

Sergei B. Kryzhov

The practice of collecting signatures via Gosuslugi without providing the voter with an EDS-certified confirmation of the performed action is flawed and promotes fraud.

Vitalii S. Kovin

Collecting signatures via Gosuslugi is one of the possible options for demonstrating support for a candidate. Like any other method, it shouldn't be the only one available, but there should be no limit on the number or percentage of signatures collected in this way.

Stanislaw Z. Raczynski

All I have in this case are theoretical speculations. Digital signature is less time-consuming for the voter, but the motivational component is qualitatively reduced: "spontaneous purchases" vanish completely. Therefore, the number of digital signatures required should be substantially less than the number of paper signatures (although it may make sense to abandon both).

Dmitry M. Khudolei

Overall, my opinion is positive. There is a de facto presumption of authenticity and validity for such signatures. Consequently, the possibility for abuse by election commissions is eliminated.

Andrei Yu. Buzin

Positive. The share of signatures collected through Gosuslugi could be increased. I suppose there could also be an opportunity to give one's signature at MPSCs and banks.

Oleg A. Molchanov

It is quite a useful innovation that is in keeping with the very spirit of digitalization of the relationship between the citizen and government bodies. I experienced it during the election of deputies to one of the regional legislative assemblies. The percentage of such signatures was higher for the independent candidate than for the self-nominated technical candidate and government representative.

Roman V. Evstifeev

Collecting signatures through government Internet services might be regarded as an interesting and useful method. However, I don't have anything to say about its safety and security, as well as about possible claims from regulatory authorities concerning techniques and methods of verification and rejection of votes cast through government Internet services.

Ivan V. Bolshakov

This is one of the few positive innovations aimed at liberalizing the signature collection procedure. Even now this practice allows independent election participants to collect quite a lot of signatures without the risk that the signatures will be recognized as invalid or inauthentic. The possibility of collecting signatures via Gosuslugi should be extended to all levels of elections, removing the limit on the number of signatures that can be collected through this system (currently they cannot exceed half of the total number of signatures collected).

Olga V. Balabanova

The procedure implies that a candidate has an enhanced EDS and the voter has a regular ESIA. The technical issues are all the same as in case of REV. From a practical point of view, self-nominated candidates supported by United Russia prefer to collect signatures the traditional way. This suggests that this mechanism makes it easier for opposition candidates to collect signatures and harder to forge them. That is, easier physically (in the most recent presidential election, a collector and a voter on Sakhalin met each other using skis) and financially.

Dmitry V. Nesterov

I don't have first-hand knowledge of this technology, although I remember complaints from Moscow candidates in 2021 that it was (at the very least) glitchy and inconvenient to work with. In the present circumstances, the concept itself is dangerous for nearly the same reasons as REV. Neither the voter (Gosuslugi user) nor the candidate has the means to check and control the work of the system. Nor should we expect any precedents for meaningful resolution of problematic situations in the courts on electoral issues in the coming years. Introducing collection practices through publicly unmonitored systems will only increase centralized administrative control and possibly influence the process even at the signature collection stage.

Artyom A. Klyga

My opinion is positive. The only time I came across it was in Vladimir Ryzhkov's campaign for the Moscow City Duma by-election in 2021. There is an important point to be made here that in his campaign, Vladimir Ryzhkov did not experience serious opposition from the administrative resource. Consequently, he had no particular trouble collecting half of the signatures in support of his nomination via Gosuslugi, which inspires little confidence due to its direct connection to the federal executive branch.

I suspect that in the case of any other candidate, who could be described as an "opposition" candidate, some malfunction may occur the Gosuslugi platform that will prevent him or her from submitting the required number of signatures by a specific deadline. Therefore, if we consider any electronic service for such a purpose, it should be at least formally developed without the participation of the executive branch. Alternatively, the election commission could be the main administrator of such a service.

Olga L. Pokrovskaya

The option of collecting signatures via Gosuslugi has never been used in St. Petersburg, so I have no first-hand experience of observing this process and its results. However, I know from feedback from party colleagues who had such experience that it was viewed positively by those directly involved in signature collection. In particular, they reported that none of the signatures collected via Gosuslugi were found to be inauthentic and/or invalid.

According to P.A.Melnikov, 37,838 digital signatures were collected in 12 regions during the 2021 election campaigns. There is no information about said signatures being recognized as inauthentic and (or) invalid [20].

The anticipated level of digital literacy of the Russian population makes it possible to use this method in all regions in election campaigns at any level. According to the Russian CEC, 90% of the number of voters in the voter register had verified accounts on the Gosuslugi portal [20].

Konstantin V. Kiselyov

This kind of practice is not very common, but all the cases I know of involve technological considerations. And this goes for both administrative and opposition candidates. Is there a need to collect signatures? We use state-funded employees or other administratively dependent people and have them "sign" under the control of their superiors. On other occasions, a tablet with a network connection is used to go door-to-door. In this sense, signature gathering is technologically exactly the same as REV.

I'd like to emphasize that REV is not the only electronic voting exercise where mechanisms for obtaining voter signatures are being tested. In Yekaterinburg, for example, signatures in support of certain areas for improvement were collected using such technology. Both the administrative method of collection and the alternative through collectors with tablets proved to be effective. Not even thousands or tens of thousands of signatures were collected in this way, but several hundred thousand signatures in total.

That said, collecting signatures via Gosuslugi is certainly convenient for substantial groups of voters. It also allows signatures to be "protected" from graphological and other examinations, signature collector errors, and other situations.

Aleksei V. Rybin

My opinion of signature collection via Gosuslugi (Unified Portal of State and Municipal Services, UPSMS) is neutral or moderately negative. I advised two candidates in the by-election in Constinuency 37 for the vacant Moscow City Duma seat in 2021, and they collected signatures via the UPSMS, among other things. From experience, these two candidates, who have broad support in the constituency, collected more signatures via the UPSMS than any other candidate in the constituency. However, they were denied registration because they failed to collect the required number of "paper" signatures in the face of yet another wave of the pandemic. "Administrative" candidates collected the minimum number of signatures via the UPSMS (from a few dozen to a few hundred, like V.A.Ryzhkov); the "paper" signatures based on which they were registered amounted to 99 to 80% of their total number.

That said, I would not fetishize signature collection via the UPSMS. It's quite difficult to get a citizen to sign in support of someone. It is easier to do it outdoors and in person than in virtual space. That's why I believe that collecting signatures via the UPSMS is orders of magnitude more difficult than collecting traditional "paper" signatures. For an unknown rookie candidate, I would rate signature gathering via the UPSMS as devastatingly challenging.

Yevgeny V. Fedin

From what I know, so far no signatures collected via Gosuslugi were recognized as invalid/inauthentic, and in this respect my opinion is positive. However, I can't ignore the risks.

1. The data regarding which candidate a Gosuslugi user left a signature in favor of may be stored for a long time and may be taken into account when providing other services or when making decisions regarding the corresponding Gosuslugi user.

2. The limitation on the number of signatures submitted to the election commission, together with the fact that the number of signatures collected via Gosuslugi is established by regional law and cannot exceed half the number of voter signatures, creates a risk that a candidate may submit signatures in support of his/her nomination from the same voters via Gosuslugi and on the signature sheet without even knowing it: FZ-67 provides no insurance against this.

3. The uncontrollable nature of the hardware and software system used for collection via Gosuslugi may result in loss or corruption of signatures collected this way; there is no guarantee that the service will be available during the signature collection period for all those entitled to leave signatures, just as there is no guarantee that the service will be operational.

Question 4. Should the required number of signatures be reduced?

Olga V. Balabanova

Yes. Infrastructure, population density (they are different in Moscow and in the regions), turnout at the last election of a similar level should be taken into account.

Stanislaw Z. Raczynski

Yes, of course it should be. Some freak won't pass even a threshold of 10,000 signatures. There is, of course, the case of Mavrodi, but for him even the current numbers would pose no issue.

Andrei Yu. Buzin

The share of signatures for nomination at the regional and federal level should be significantly reduced. This share should be no more than 0.5% for elections of all levels. On top of that, it is necessary to bring back the election deposit in local elections.

Sergei B. Kryzhov

In my opinion, the existing number is at least twice as high then it should be. In some cases, the cost of collecting signatures is a major expense for the candidate. Let the candidate collect as many signatures as he/she wants, because collecting signatures is part of the campaign, but the number of signatures required for registration should be reduced.

Olga L. Pokrovskaya

As was stated earlier, it is necessary to make the procedure simpler, bring back the election deposit as a possible condition for candidate registration, and significantly reduce the required number of voter signatures in support of nomination of a candidate (list of candidates).

Mikhail V. Titov

A significant change in procedure may also require a significant reduction in the number of signatures. However, this does not exclude the possibility of a reducing the number if the procedure is maintained.

Dmitry M. Khudolei

It should be reduced in any case, whether or not a procedure for collecting signatures in designated locations is introduced. As a reference point, I consider the provision in Article 1.3 of the Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters 2002 [21: 333] (not more than 1% of the number of registered voters in the constituency).

Konstantin V. Kiselyov

Naturally, the number of signatures needs to be reduced. The quantitative criterion should be a reasonable understanding of the threshold that would keep "political lunatics" and freaks from participating in elections. At the same time, reinstating the regulations related to the election deposit could be an appropriate substitute for the signature collection.

Nikolai I. Vorobyov

I am convinced that it is necessary to legally reduce the required number of signatures in support of candidates (from 0.1% to 0.5%). In any case, the upper limit should not exceed 0.5%. Alternatively, it shouldn't exceed 1%, which is what the Venice Commission recommends. At the same time, the allowable surplus (stock) of collected signatures submitted to the election commission for registration should be increased to 20-25%.

Artyom A. Klyga

If the option of completely abolishing the signature collection procedure is not considered, then the required number of signatures for regional and federal elections should definitely be reduced by a factor of three or even four. However, it should be noted that such a measure will not help if there are all available grounds for recognizing a signature (signature sheet) as invalid or inauthentic.

Yevgeny V. Fedin

Absolutely. The need to organize election headquarters structures to collect and verify signatures or to engage external organizations with such structures is flawed, given that errors in signature collection result in the candidate losing his or her status. There shouldn't be such a scenario that a candidate's rights are affected because of the fault or mistakes of others when he or she doesn't even have the opportunity to ensure that there are no such mistakes.

Roman V. Evstifeev

If the practice of signature collection cannot be abandoned for the time being, then surely the number of signatures ought to be reduced substantially.

There is likely to be some correlation between the effectiveness of signature collection and the number of voters and therefore the number of signatures collected. Perhaps there is some limit to the number of voters, after which signature collection becomes an ineffective tool for recording the will of citizens.

Aleksei V. Rybin

It depends on the overall approach to getting candidates on the ballot. In municicpal elections in Russia, there is no need to reduce the quota since it is sufficiently generous as it is. In sub-federal and federal elections (assuming administrative pressure is ruled out), I wouldn't change a thing either. With proper organization and sufficient popularity of an independent candidate, he or she will be able to meet the current legal requirements for the number of signatures to be collected. Even if the collection procedure is not made more flexible, which I suggested above (response to question 2).

Oleg A. Molchanov

Currently, the required percentage of voter signatures for different elections varies by a factor of 6 (from 0.5% for municipal elections to 3% for regional elections), even with a comparable number of voters in specific constituencies. Since we are talking about the constitutional active suffrage of the citizens of the Russian Federation, it seems appropriate to introduce a unified scale of the number of percentages of the total number of voters in a given constituency, which would depend only on the number of voters in a particular constituency and not on the election level. The greater the total number of voters in the constituency, the smaller the percentage should be. I think 0.5 to 1% of the overall population of voters is sufficient.

Aleksandr V. Grezev

Yes, the number of signatures to be collected in constituencies in regional and federal elections should be significantly reduced. Quite a reasonable threshold is 0.5% of the voters in the constituency, as intended for local elections. For party lists for the State Duma and presidential elections, the first thing to do is to remove the restriction on the maximum number of signatures to be submitted from one region. It would also make a lot of sense to significantly increase the number of signatures that can be submitted to the commission rather than limiting it to a 5% or 10% surplus. Meanwhile, the commission's task should be to recognize as valid the number of signatures required for registration out of the total number of signatures. Alternatively, signatures could be submitted in two stages. If a candidate is short of valid signatures after the first submission, he or she may be allowed to submit the missing number of signatures.

Ivan V. Bolshakov

We should strive for standardized conditions for the registration of candidates and candidate lists from parliamentary and non-parliamentary parties. Therefore, the first thing to do is to exempt candidates from parties that received the support of at least 0.5% of voters in the last State Duma election from collecting signatures for any type of election. The existing requirements for non-parliamentary parties to collect 200,000 signatures for parliamentary election or 100,000 signatures for presidential election lose their point, as said parties have recently secured the support of at least a comparable (and in reality larger) number of voters, and no additional confirmation of their legitimacy is required. For new parties and parties that gained less than 0.5% in parliamentary elections, as well as self-nominated candidates, the number of voter signatures should not exceed 0.05% of the number of voters in any election (for municipal elections, a minimum number of signatures is allowed).

Vitalii S. Kovin

If the procedure is substantially changed from "signature collection" to "public show of support," the number of notional "signatures" should be substantially reduced. The specific number is a matter of debate. Moreover, public support from elected politicians (deputies of different levels, local self-government and regional heads), who themselves have previously received support from voters, should also reduce the established number (tentatively, a vote of support from a State Duma deputy and a legislative assembly deputy is equal to 500 and 100 regular votes, respectively). In a similar fashion, party support (a public decision made at a congress or conference to join in supporting a self-nominated candidate or a candidate nominated by another party) should reduce the number of signatures required, for example, by a fraction of the percentages obtained by the party in the last election at the corresponding level.

If the existing procedure remains in place, the required number of signatures for federal elections for self-nominated and party candidates should be reduced to 50,000.

Question 5. What are the methods for tackling the issue of voter signature forgery?

Dmitry M. Khudolei

If we're talking about using the signature collection procedure in specially designated locations with the participation of members of election commissions or via Gosuslugi (taking into account the suggestions made above), then forgery will no longer be an issue.

Ivan V. Bolshakov

Signature forgery is facilitated by the unreasonable number of signatures required for registration, as well as the complexity of the procedure. Therefore, the primary method of dealiing with forgery is to reduce the number of signatures required, simplify procedures and partially outsource signature collection to the Internet, MPSCs and election commissions.

Nikolai I. Vorobyov

First, the number of voter signatures required for registration should be significantly reduced. Second, the very procedure of verifying collected signatures should be made simpler. Third, if such cases arise, law enforcement agencies should be involved in the verification and investigation.

Olga L. Pokrovskaya

As was stated above, signatures should be collected digitally. The procedure for collecting signatures via Gosuslugi eliminates forgery as a possibility.

One more thing: the fewer signatures required, the less forgery there will be. And having the option of making an election deposit instead of collecting signatures will minimize the volume of forgery.

Dmitry V. Nesterov

Open lists (of both voters and signers), for example. However, in an unhealthy political climate, this might pose other risks for the signing voters.

Trying to answer such questions is like trying to mend a very old shirt. With each new patch, there are new spots where the fabric splits. And one immediately starts to consider buying a new one.

Mikhail V. Titov

First, by ensuring thorough monitoring of the organization and implementation of signature collection. Monitoring should be carried out by professionals with specialized training and coordinated with election commissions.

Stanislaw Z. Raczynski

Notary public is the only reliable way to prevent forging of signatures (notary fraud, as it seems to me, is not to be feared, as the cost is clearly less than the cost of a notary license). But this is a purely theoretical option due to apparent technical difficulties (even if we leave aside the cost of notary services, even Moscow doesn't have enough notary publics).

Aleksei V. Rybin

The answer to this question depends on an extra question: who should bear the burden of this struggle? I would get rid the signature verification process at the election commission altogether. Challenging a signatures and providing proof that it's inauthentic should have been left to the competitors in the constituency and to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts. If such a struggle is waged by the commission, the downside is the risk of administrative discretion and the resulting administrative arbitrariness. These risks are mitigated if the signature dispute is moved to court and entirely driven by an opponent in the same constituency.

Andrei Yu. Buzin

This is quite difficult to do when there are no conditions for free and fair elections. The very reduction in the number of signatures required, as well as the use of identifying signature collection methods (see answers to the previous questions), may reduce the share of forgery dramatically.

Cosmetic measures may include confirming one's signature via MPSC or bank, attaching a copy (or photo) of one's passport to one's signature, the possibility of verifying one's signature via polling.

Konstantin V. Kiselyov

The simplest and most obvious way to tackle the issue is to reduce the number of signatures required and to reduce the list of grounds for invalidating a voter's signature. The signature collection process itself should become more substantial than procedural. However, if collection and verification procedures are made simpler and quantitative indicators are reduced, the penalties for falsification (forgery) of signatures should be made more severe.

It could also be possible, when clear signature analysis software becomes available, to use machine verification methods followed by manual double-checking.

Aleksandr V. Grezev

The best way is to move as far away from signature sheets as possible and encourage a switch to digital signatures, which will be many times more genuine than manufactured and doctored ones. A significant reduction in the number of signatures will also help to avoid forgery. I've seen decent democracy-oriented candidates (who would have likely won the election) who had to submit partially doctored signatures, because the signature barrier, paperwork and costs were too high to collect them honestly. That said, I find it interesting that signature verification by artificial intelligence systems can detect doctored signatures more honestly and efficiently than handwriting experts. With objective commission work without administrative pressure, this could be a benefit.

Yevgeny V. Fedin

To require election commissions to respond to statements on offenses under Article 5.47 of the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses, request information from election commissions and make public the statistics on the number of protocols drawn up by authorized members of election commissions with a deciding vote on administrative offenses under Article 5.47 of the Сode, as well as on refusals to initiate cases on administrative offenses.

To require election commissions, in accordance with Clause 5 of Article 20 of the Federal Law No. FZ-67, to submit to law enforcement agencies with requests to conduct checks of suspicious signatures for the presence of an administrative offense under Article 5.46 of the Code, as well as crimes under Part 2 of Article 142 of Russia's Criminal Code, to request information and make public statistics on the number of administrative and criminal cases initiated, as well as on refusals to initiate such cases.

Artyom A. Klyga

If we presume that signature collection system is preserved, we may consider the following method to combat fraud: selective survey of voters using an electronic system operated by the election commission. The election commission would selectively send out notifications to voters, for example, to their Gosuslugi accounts, that they had left their signature in support of the nomination of a certain candidate. If the voter does not take any action after receiving the notification, the signature shall be recognized as valid in the absence of any other claims against it. If there are available resources, such a survey can be conducted using the Russian Post's electronic system for mailing registered letters in bulk.

In municipal elections where a candidate needs to collect a small number of signatures, for anti-fraud purposes, signature collection can be organized at a specific location, for example, in the premises of the election commission, where the identity of the person signing for the candidate can be confirmed once more by an election commission member. Under such circumstances, most grounds for recognizing signatures as invalid or inauthentic should not apply.

Vitalii S. Kovin

It is practically impossible to deal with technical fraud (forging of signatures in signature sheets) in the existing format by other means than those already employed by election commissions (databases, handwriting experts). However, the imperfection and selective application of these anti-fraud instruments only further aggravate the situation. I believe that the only way to remedy the situation is to make the list of signees public.

Actually, there are two main reasons for fraud: 1) the inability or unwillingness of the candidate and his/her headquarters to collect the required number of signatures, in which case the headquarters arranges to "doctor" them en masse; 2) the desire of the collector(s) to make money by minimizing their efforts, or competitors hiring stooges to intentionally forge signatures while posing as collectors. In such a case, as a safeguard against "freeloaders" and "stooges", the headquarters should set up an internal quality control of signatures. In the first case, the headquarters is deliberately forging signatures, while in the second case it becomes a victim of the persons involved in the collection, and since the falsification (forgery) of signatures constitutes the body of administrative or criminal offenses, the detection of their signs should automatically be accompanied by investigative actions (verification) in respect of suspicious signatures and their collectors. With all output data available (names, addresses, dates of birth of signatories and collectors recorded), verification can be done in a matter of a few days.

As for the period of verification by the election commission, it should be extended. A confirmation based on the results of the verification (with appropriate conclusions) that certain signatures (for deceased persons, for relatives, etc.) were indeed forged should result in cases being initiated and brought to court before the end of the election campaign. In other words, it is necessary to make this legal mechanism so clear that, when falsifying, the collectors or headquarters should understand that in fact they themselves admit to the offense by providing evidence and their personal data. The risks become too great.

Olga V. Balabanova

Going digital is the ideal way to do this. Secrecy of the ballot does not mean secrecy of the nomination. I think it would be possible to use Gosuslugi to notify voters whose signatures are affixed or found to be disputed of these facts. And, if they disagree, they may file a complaint.

As to whether we need to combat it directly, we need to learn to identify it first. Say, here's a certificate issued by the Ministry of Internal Affairs: the voter is deceased. All it takes is a couple of administrative or criminal cases and people will stop doing it. So far, these certificates are nothing more than grounds for rejection without consequences.

There is also the issue of verifying other people's signatures. Apart from the members of the working group, a candidate who has submitted a sufficient number of signatures may participate in the verification (those who did not collect do not participate in the verification and do not see the signatures). The only way for them to look at such sheets is to go to court. However, in the fall I was banned from examining them, both as a lawyer and as a candidate in court, and only after an appeal in cassation was I granted permission to look at them for a limited amount of time, without the right to take photocopies and take notes. As recently as 6 years ago, the courts allowed photocopies. Now they don't, and they won't allow to take notes either. Six years ago, as a member of the working group, I managed to identify forged signatures and find this voter. But there were no legal repercussions. I then filed a special opinion as a member of the TEC and voted against registration.

Roman V. Evstifeev

I suggest we don't combat signature fraud in any way. The very concept of "fraud" and its attributes can be easily manipulated, depending on the formal and informal requirements for the signature collection process, the signature sheets, and the signatures themselves.

I can't help but cite a historical example to divert a bit from the political relevance of the issue. One of the recognized foundations of Russian feudal law was the so-called Sobornoye Ulozheniye of 1649, a code of laws that was in force in Russia for almost 200 years. The form in which this Ulozheniye was adopted or approved was the signatures of the participants of the Zemsky Sobor, a total of 315 signatures ("manuscription", as it was then described) of electors from 116 cities. However, if one looks at these "manuscriptions" from a formal point of view, one can easily find grounds for serious arguments in favor of many of such manuscriptions being invalid or even forged. In this way, one can easily cast doubt on the entire legal foundation of both feudal Russia and the Russian Empire and all subsequent forms of statehood in Russia.

According to historians, "manuscriptions" on the reverse side of the scroll of the Sobornoye Ulozheniye of 1649 are extremely difficult to decipher, in some parts it is difficult to vouch for the correct reading, the signatures are located irregularly, some columns are signed by two or more persons, in some cases the signature of one person is stretched over several columns, there are cases when there are no signatures at all in the required spaces [31: 10]. In general, there is every reason to recognize some of the signatures as forged.

It should be noted that this was a case when signatures were made by a relatively small number of specially assembled people, specially prepared for this very endeavor, who carried out the procedure under the direction of the managers — the dyaks. The absence at that historical moment of election commissions or other bodies authorized to verify and establish the authenticity of signatures saved Russia from further existence without a basic law document.

Question 6. How to prevent arbitrariness in the verification of voter signatures?

Konstantin V. Kiselyov

We'll have to wait for the political and judicial systems to change.

Roman V. Evstifeev

It is impossible to prevent arbitrariness in the verification of voter signatures until the will of the voter expressed in the signature is considered more important than the will of the verifiers.

Sergei B. Kryzhov

I'm having trouble answering this question. Only by proper recruitment of election commissioners.

Dmitry M. Khudolei

Changing the signature collection procedure, as I wrote earlier. Only then can the concept of "invalid signature" be removed from the legislation altogether.

Stanislaw Z. Raczynski

I could repeat my answer to the previous question. Requiring notarization of signatures would make signature verification unnecessary and qualitatively reduce the administrative procedure for their acceptance, but it is impossible to ensure this; and any verification of signatures already affixed will inevitably be accompanied by arbitrariness on the part of the verifier.

Olga V. Balabanova

A poll is a good format. All interested parties should be allowed to participate in the verification, not only those who submitted signatures and not only during the period of verification by the working group. The handwriting expert should be warned of criminal liability. Candidates should have the right to bring their own handwriting experts with proof of education and also warned of criminal charges. The handwriting expert should come from outside the public government system to comply with the principle of non-interference.

Yevgeny V. Fedin

By making it easier for independent persons to become part of election commissions, by attracting mass media attention to the procedure—having the outlets send their representatives to cover what is happening during signature verification. As for municipal elections: by abolishing the change in the law that led to the fact that elected candidates and electoral associations admitted to seat allocation lost the opportunity to appoint members of territorial election commissions with consultative capacity.

Aleksandr V. Grezev