Presidential Elections in Mongolia, 2017: Old Stereotypes or Democratic Transit in Action?

Abstract

The article is devoted to the Presidential elections in Mongolia, which took place in 2017. These were the first two-round elections in its history. The election campaign was held with scandals, withdrawals of one of the candidates and led to an unexpected result. The author revealed the role of Mongolian CEC and public opinion, and also analyzed the election campaigning of candidates and observation at precincts. In addition, some conclusions are drawn on the way a change of power can affect the state’s foreign policy and relations with neighboring countries.

On July 7, 2017 a candidate from the Democratic Party Khaltmaagiin Battulga was elected Mongolian President in the second round of the elections. These were the first two-round presidential elections in the country’s history. Presidential elections of our eastern neighbor arouse interest because they are intertwined with several concerns, including foreign policy. Having lost all its influence in Mongolia in the 1990s, Russia is trying to find its own thread of a new relationship with the young democracy, but does not succeed completely.

Besides, for many decades, Mongolia, along with the countries of Eastern Europe, was in the sphere of the Soviet Union’s interests, participated in many projects of the socialist bloc and eventually felt all the hardships of the collapse of the USSR and the end of financial support.

After that, from the beginning of 1990, Mongolia quickly abandoned communism and socialism, without any problems and serious political cataclysms. Political experts and scholars, as a rule, call the country an “anomalous zone” that sometimes deviates from the democratic path of development, so there is little surprise that 15 governments have changed in the country during 26 democratic years. For more than a decade, Mongolia has been also called “the second Saudi Arabia”, because the country is rich in non-ferrous metals, coal, uranium and oil. All the major countries have started a struggle to access them; American political analyst Ariel Cohen called the response of the Mongolian authorities “resource nationalism”. Local scholars call the geopolitical position of Mongolia “a sandwich”, as the country is squeezed between its two largest neighbors, Russia and China [1]. At the same time, Mongolia’s political elites have been trying to pursue an equilibrium policy without giving preference to any of the parties, although the Asian vector seemed to be more conspicuous, and political scholars often refer to Mongolia as the “first third country”, “second third country” etc. [5].

This created the ground for the emergence of a leader to the protest moods that manifested themselves in 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2011. There were a lot of questions to the former governments, starting from an increase in “resource rent” from the major deposits of natural resources (which, incidentally, are being developed by international companies).

According to the 1992 Constitution of Mongolia, a citizen of the country over 45, who was born there and who has a five-year residency requirement, can become the president of Mongolia. The president is elected for four years; he can be re-elected, but only once. This is stated in Clause 6, Article 31. Besides, the Constitution provides for two rounds of elections, if, according to the results of the first, no candidate gets 50% plus one vote. Then the two candidates with the most votes proceed to the second round, which is held two weeks after the first. If in the second round the turnout does not exceed 50%, the law provides for holding new elections with new presidential candidates.

In general, the president’s powers differ from the traditional Russian model. It is closer to the European one, since the president nominates the leader (representative) of the winning political party for the office of Prime Minister, but the president’s powers are broader, although Mongolia is a presidential-parliamentary republic.

The President of Mongolia, according to the law, is the embodiment of the national unity. The President is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces; he has the right to veto the Great State Khural’s legislation, to participate in lawmaking, to represent the country abroad, to appoint judges and ambassadors. The President also nominates the head of the Independent Authority Against Corruption and the General Intelligence Agency, the two most influential institutions in Mongolia.

Political parties with representation in the State Great Khural can nominate presidential candidates.

Other political forces have the right only to support those nominated candidates. In its report on the results of the previous presidential elections in Mongolia in 2013, the OSCE mission mentioned this as a negative fact, because “the OSCE allows nominating independent presidential candidates”.

There were also questions about electoral legislation as it was adopted without public discussion. In early 2017 a number of political figures raised the issue of amending the Constitution and proposed the expansion of the rights of non-parliamentary parties, but the process did not go beyond the proposals.

Since the first 1992 parliamentary elections in Mongolia, there has been a struggle between the two major political parties – the Mongolian People’s Party and the Democratic Party. Much depends on the outcome of this struggle: representatives of which party will occupy the most influential government offices and take over the major state-owned enterprises.

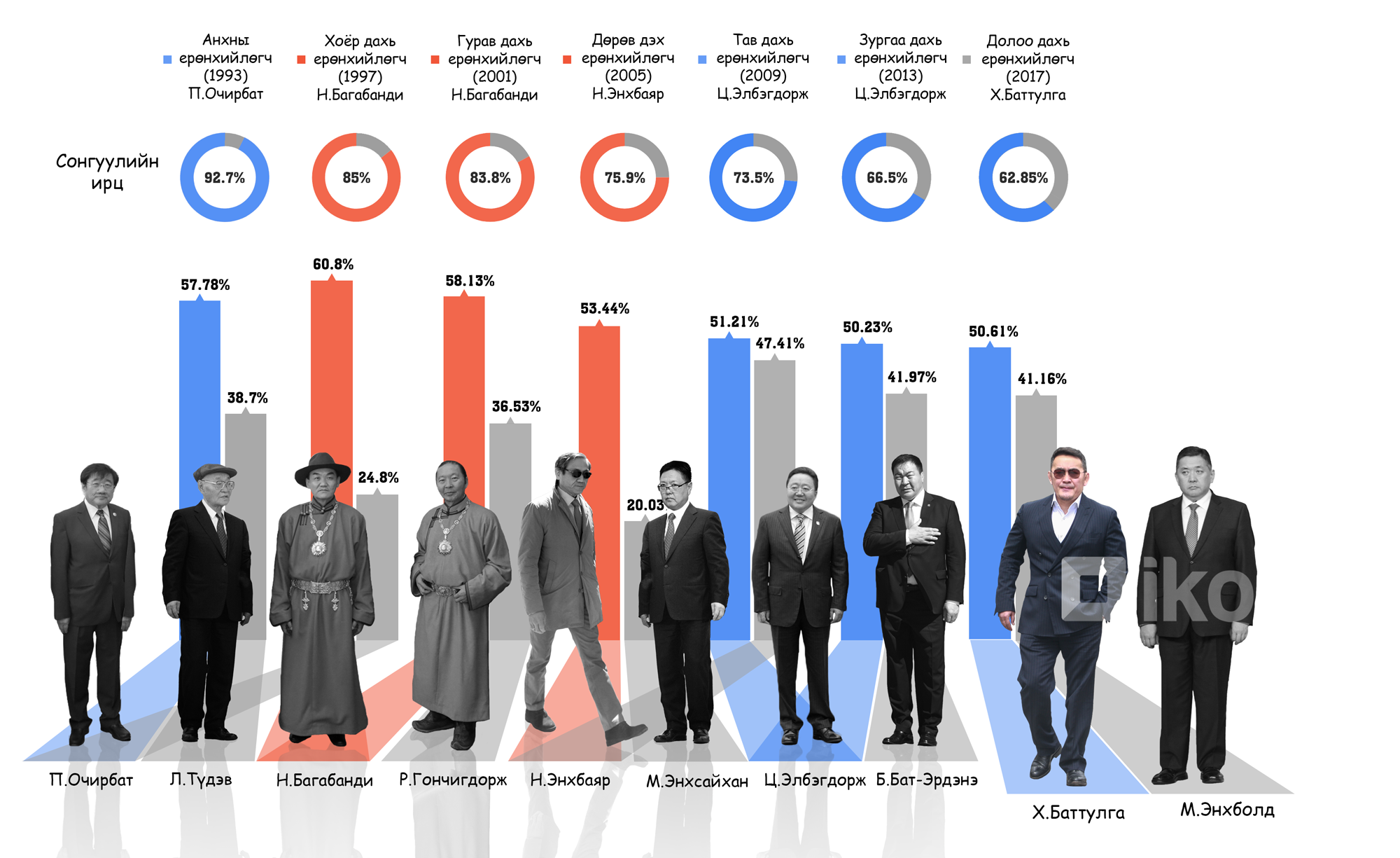

Previously, Mongolia’s presidential office was occupied by the winners of elections: in 1990 (the President was elected by the Parliament) and 1993 – the representative of the Mongolian People’s Party Punsalmaagiin Ochirbat (92.7%), in 1997 and 2001 – the representative of the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party Natsagiin Bagabandi (85% and 83, 8%), in 2005 – a member of the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party Enkhbayar (75.9%), in 2009 and 2013 – a member of the Mongolian Democratic Party Nambaryn Elbegdorj (73.5% and 66.5%). All four presidents were educated in the USSR: Ochirbat graduated from Leningrad Mining Institute, Bagabandi – from Leningrad Refrigeration Technology College and Odessa Technological Institute of Food Industry, Enkhbayar – from Moscow Literary Institute, Elbegdorzh – from Lviv Higher Military-Political School. Since President Elbegdorj did not have the right to run for elections, Mongolia was anticipating a new, fifth in its history, president of the country.

After agreeing the date with the standing committee on state building of the Great State Khural of Mongolia, the elections were to be held on June 26 according to the chair of the Central Election Committee Choinzon Sodnomceren’s announcement made on January 26, 2017. In Mongolia, elections are not held on a day off, because it is considered wrong to be busy with public matters on the day off.

The election campaign began long before the announcement date, because in the summer of 2016 parliamentary elections took place, in which the Mongolian People’s Party won, receiving many more mandates in comparison with the previous elections. The Democratic Party, despite the support of the president, faced a crushing defeat in the elections, having received only 9 out of 76 seats. On the eve of the elections, a thorough reform of the electoral legislation had been carried out, and instead of a mixed system (previously 48 out of 76 deputies were elected in single-mandate constituencies and 28 were on party lists), the State Great Khural was elected only in single-mandate constituencies, which aroused criticism from smaller parties. In addition, the mandatory 50% voter turnout was returned, and voters residing outside the country that constitute one tenth of all voters were to vote only in their precincts, which was completely impossible [16].

After the defeat of the Democrats, the party started the discussion of a presidential candidate nomination. Ex-prime-ministers Norovin Altankhuyag and Rinchinnyamyn Amarjargal, the former mayor of Ulaanbaatar Erdeniyn Bat-Uul and the former Minister of Transport Khaltmaagiin Battulga in turns announced their intent to run for president. On May 3, 2017, as a result of inner-party voting, Battulga was nominated a party candidate.

was born in 1963 in Ulaanbaatar. He graduated from a secondary school and then an arts school, becoming a professional artist in 1982, but having no university degree. In 1979-1990 he was a member of the Mongolian National wrestling team and won the world cup championship. Since 1990, he was engaged in business, being the head of the companies “Zhenko”, “Makh Impex” and the owner of the hotel “Bayangol”. In 2004 he was elected to the Great State Khural. In 2008-2012 he was Minister of Roads, Transportation, Construction and Urban Development. In 2012 he was re-elected to parliament, then for two years was a Minister of Industry and Agriculture. According to the media, he ranks third on the list of the top richest people in the country. Married to his second wife Angelica Davain, who is Russian. Father to four children.

Image 1. Campaign banner of the future President Kh.Battulga

Several scandals have been associated with the name of Battulga in Mongolian politics. In 1997, he was involved with the “case of 17 containers of alcohol” (illegal imports of alcohol), but the case fell apart and was never taken to trial. In 2016, he was suspected of abuse of power. However, he is better known for his philanthropy, since his company created the world’s largest Genghis Khan statue and the 13th Century Theme Park which are currently the most popular sightseeing attractions of Ulaanbaatar [4].

However, the first party to nominate its candidate was the Mongolian People’s Party. The results of the popular vote in which almost 50,000 people took part were presented at the party conference on May 3. Five candidates were nominated by voters, but three of them (the minister of defense Badmaanyambugiain Bat-Erdene, the vice-minister Ukhnaagiin Khuralskh and deputy Enkhtyushin) immediately withdrew. Of the two remaining candidates, chairman of the State Great Khural Miyegombyn Enkhbold and vice-speaker Tsendiin Nyamdorj, the former won the open vote.

was born in 1964 in Ulaanbaatar. In 1982 he graduated from secondary school, in 1987 from the Mongolian State University. Received a master’s degree in economics. He is full member of the International Informatization Academy, Honorary Doctor of the Orkhon University (Mongolia) and Kwangwoon University (South Korea). Since 1987 he worked in the economic sphere. He started his career in politics in 1996, becoming the Chairman of the Presidium of the Chingeltei Districts Khural of Citizens Representatives. In 1999-2005 he served as mayor of Ulaanbaatar. In 2005 he was elected a deputy of the Great State Khural. In 2006-2007 he served as Prime Minister of Mongolia, in 2007-2012 – as Deputy Prime Minister. In 2012, having won parliamentary elections, he was elected deputy chairman, and after the parliamentary elections on June 29, 2016 – chairman of the Great State Khural. Married father of two daughters.

Image 2. Campaign banner of the presidential candidate Enkhbold

In public opinion, Enkhbold had a reputation as an experienced politician. Occupying high positions in the government, he initiated the construction of the new international airport in Hushigiyn Hondiy, as well as launching Mongolian satellite MONGOLSAT into orbit. However, he was allegedly involved with the land distribution scandal when he was the mayor of Ulaanbaatar, but then the matter was not taken to court [4].

The Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party, at a closed meeting on May 5, nominated its chairman and former president Nambar Enkhbayar [4].

was born in 1958. He graduated from the Moscow Literary Institute (1980) and the University of Leeds (Great Britain). In the 1980-1990's he worked as an interpreter from the Russian language, served as the secretary-general and vice-president of the Union of Mongolian Writers. In 1985 he joined the MPRP. In 1992 he was elected to parliament and was appointed Minister of Culture of Mongolia. He won four times in the parliamentary elections. In 2005, the MPRP nominated him for the presidency. He won the first round of elections with 54.2% of the votes. In 2009 he was nominated again, but lost the election. In the spring of 2012 he was arrested, charged with corruption and illegal sale of state-owned property, and sentenced to four years in prison. In August 2013 he was pardoned by President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj and released from the rest of his jail term.

However, the Central Election Committee of Mongolia refused to register Enkhbayar at its May 14 meeting. The first reason was that his conviction would end on August 2, 2017. The second reason was that according to the law the candidate does not have the right to stay out of the country for more than one year during the last five years, and the CEC was able to prove that Enkhbayar had been treated for thirteen months in the Republic of Korea (from August 13, 2013 to October 9, 2014).

The candidate himself and the party activists protested against the decision. Enkhbayar said at the meeting of the CEC that “you, as well as scammers, cannot eat Mongolia,” and the candidate’s fans made riots and promised to start a hunger strike, but later abandoned the idea.

The MPRP considered several candidates to replace Enkhbayar. Among them were ex-deputies of the State Great Khural Tserendashin Oyunbaatar, Tserenkhiygiiin Sharavdorj, academician-lawyer Sodovsarangin Narangarel, trade union leader Sainhugiin Ganbaatar. When the academician learned that the candidate should pay 10 billion tugriks (about $ 4 million) to the party for the elections, he immediately withdrew. On May 16, Ganbaatar was nominated as a candidate from the MPRP.

The decision-making process was not easy. Baasankhuu, the only party member in the parliament, opposed the nomination of Ganbaatar saying, “The MPRP has 114 thousand members. Such a large party cannot be represented by a person about whom it is not even clear whether he has a higher education. I am the only party member who represents the MPRP in the Great State Khural. I will send an official letter to the Mongolian Election Comittee stating that I am against the candidacy of Ganbaatar. Such decisions of the MPRP’s leaders make me cancel my membership in the party.” But the party members did not support Baasankhuu [11].

was born in 1970 in the Bayankhongor aimak. In 1997-2000 he served as a bank manager in the bank “Sala General” in the UK, in 2001-2002 – as Special Assets Director at KhAAN Bank. In 2002-2003 – as a lecturer at the Institute of Finance and Economics, in 2003-2005 – at the Academy of Management. In 2005-2007 he was the head of the Movement for Urgent Renovation, in 2006-2008 he was the leader of the movement “National Soembo”. In 2007-2011 he was the leader the Education, Culture, and Science Workers’ Trade Union Association. In 2007-2012 – President of Mongolian Trade Unions Association. Since 2012 he has been a member of the Great State Khural. Speaks English and Russian.

Image 3. Campaign banner of the presidential candidate S.Ganbaatar

During the election campaign, Ganbaatar concluded a “Liability Agreement” with the Mongolian people. The document, in addition to promises to increase salaries, pensions and support for the poor, states the importance of combating corruption.

He announced his intention to attract Russian investors to the country in case of a victory, since he had worked for some time in Russia, but, in his opinion, Mongolia needs to maintain a balance in relations with China as well.

On May 17, all the three candidates were registered; many Mongolian and international newspapers wrote that Enkhbold would win, because he had ample starting opportunities and experience, he had participated in negotiations with the IMF to allocate a tranche of 5.5 billion dollars. The remarkable thing is that he could have been prime minister after the victory of the Mongolian People’s Party in the summer of 2016, but, unexpectedly for many, he refused, becoming the speaker of the parliament instead. The Western press claimed that this was an intentional step, since already then Enkhbold was going to become president. The media also called him “man-fog” because some of his actions seemed ambiguous.

The name of the candidate from the MPRP is associated with the loudest scandal in this election campaign. An anonymous source uploaded a video recorded on May 23, 2017 to social media. The video was recorded in the home of the candidate from the MPRP Sainkhuugiin Ganbaatar; he is seen receiving illegal donations of 50 million won (2.62 million rubles) from a citizen of the Republic of Korea, and promising to help foreign citizens in response to their financial assistance.

On June 22, the head of the third criminal police department said that the Central Election Committee of the country received official letters from political parties with a request to verify the video. The candidate himself declined to comment. The police sent the case to the criminal court of first instance in Bayanzurkh district of Ulaanbaatar for a decision, but the court refused to consider the case, citing lack of verification, and returned all the materials to the police.

On June 23, police said that the record was genuine, no signs of video editing were found, and again sent all the documents to court. If the court had found a violation of the electoral legislation, the candidate from the MPRP could have been denied the right to run for the presidency. But the court did not have enough time to consider the case, since the documents had arrived on June 23, Friday afternoon, the last working day before the elections. Thus, candidate Ganbaatar remained on the ballot [15].

On the evening of June 24, the Mongolian National Public Television broadcasted a debate of all candidates, where the domestic and foreign policy issues were discussed. Among the most urgent tasks the fight against corruption, the solution of economic issues, the problems of food security, and the change of mining industry legislation were mentioned. However, the Mongolian voters were extremely dissatisfied with the debate, believing that the national television obviously supported candidate Enkhbold as he was not asked a single serious question [15].

The first round of presidential elections was held on June 26. The polling stations were open from 7.00 a.m. to 10.00 p.m. According to the national legislation, voting day is a non-working day. On this day all shopping centers and markets are closed for the citizens not to be distracted from voting.

A total of 1,983 polling stations were open in the country. According to the General Authority for Intellectual Property and State Registration, 2,002,301 citizens of Mongolia had voting rights. However, only 1,978,294 of them were included in the voter list. Another 44,274 people were listed as “temporarily excluded” (citizens who were in temporary confinement cells, or those on business trips). Such voters can come to their polling stations and vote after the identification procedure, including fingerprint verification.

The day before the voting day, on June 25, those who are involved in extinguishing fires, kept in detention centers, unable to come to the polling stations due to health issues, members of election commissions and those sent to forced labor can vote using portable ballot boxes.

Image 4. Polling station for presidential elections in rural areas

On the days of voting and vote counting, June 26-27, the mayor of Ulaanbaatar decided to ban public meetings, cultural and sports events in the city, as well as the sale of alcohol [12].

Surveillance cameras were installed at all polling stations and it was stated that in order to prevent falsifications, all ballots would be recalculated by the CEC the next day; and one or two police officers were sent to each polling station.

17,000 observers from political parties and 123 observers from 37 countries representing the PACE, the OSCE and foreign media were accredited to the elections. The OSCE / ODIHR carried out long-term observation of the elections, saying that this would increase public and foreign confidence in electoral activities in Mongolia, and the OSCE / ODIHR assessments and recommendations would contribute to further improving the electoral process in Mongolia.

Citizens of Mongolia living abroad could vote on June 10 and 11 at 45 polling stations in 33 countries. Out of seven thousand such voters, 66.8% voted. The votes were counted only after the end of the official voting on June 26 [7]. The Electoral Code of Mongolia prohibits the exit polls on voting day, therefore official information is provided only by the CEC.

A live broadcast of the votes counting was on all Mongolian TV channels. Traditionally, preliminary results are announced within an hour after the closure of the polling stations. 1, 318, 511 voters voted on June 26. The turnout was 66.5%. The first results were sensational: Battulga was the winner with 517,478 votes, Ganbaatar, who had been left on the ballot despite the scandal, was the second, while the incumbent Speaker of Parliament and the leader of the ruling party Enkhbold took the last place [8]. However, after summarizing the official results, Enkhbold returned to the second place with 411,748 votes, and the the MPRP candidate was the third with 409,899 votes. 1.3% votes were against all candidates, which was the highest level in the history of the presidential elections. In Mongolia there is no column “Against all”, and blank ballots in the urns mean voting against all candidates. As it turned out later, according to official results, the number of votes given for Enkhbold increased by 35,000, due to the increase in the number of voters. Ganbaatar himself stated that he did not recognize the election results, and declared these 35,000 “dead souls” [10]. The leaders of the MPRP claimed that the CEC of Mongolia had smeared the country’s reputation and denigrated the Mongolian democracy. However, the Central Election Committee left Ganbaatar’s statement without attention and serious analysis.

In the evening of June 26, the second round of elections was scheduled for July 9. According to the CEC, 5 billion tugriks (125,341,274 rubles) were needed to conduct it [13]. According to the law on the state budget of Mongolia for 2017, the total cost of holding presidential elections in Mongolia was 14.9 billion tugriks. This was less than in 2013 (15.8 billion tugriks). The total expenses for each candidate’s campaign was 3.9 billion tugriks, and for one political party or coalition they amounted to 6.8 billion tugriks. The total cost of the entire presidential campaign, including state and non-state expenditures, amounted to 47 billion tugriks.

Moreover, the CEC leaders announced that it would take some time to print new ballots, to bring voting machines and install new program for counting votes in aimaks and somons, and to deliver updated equipment to polling stations.

According to the national law, only 4,816 Mongolian citizens registered to vote in the presidential election abroad would have the right to vote in the second round. Under the pressure of the political parties, the Central Election Committee postponed the elections until July 7, as July 9 was one of the days when many Mongols celebrate the national holiday of Nadom (Naadam) and go out of town, which could seriously affect the turnout.

Those dissatisfied with the results of the first round launched a social media campaign “Protest Voice”. Its essence was explained in an interview to IA REGNUM by one of its activists, the Mongolian State University professor Damdinsuren Oyunsuren: “It is not a second round, but repeat elections that we have to hold. For that, on July 7 voters must vote against all. I hope, during the repeat elections our political parties will give voters the opportunity to vote for a candidate with a good education and high ethics. The elections held showed that “mafia” parties should not be underestimated. About 1.3% voted against all; this is an important signal of a demand for more active intra-party reforms” [14].

In the second round, Battulga consolidated his success. 610,382 voters (50.6%) voted for him. 496,593 voters (41.16%) voted for the second candidate Ganbaatar. 99, 425 ballots (8.24%), were declared invalid, which became a kind of record in the political history of modern Mongolia. The turnout for the elections was 60.9%, which also became a national anti-record. The turnout for the previous elections had ranged from 66.5% to 92.7%.

Image 5. Table "All presidents of Mongolia and their election results"

The Central Election Committee of Mongolia received 15 complaints, appeals and petitions, including those for the postponement of the second round of voting, for the re-counting of votes, for admitting the campaign calling to cast a blank vote illegal. All complaints, appeals and petitions were rejected. The OSCE observers assessed the Mongolian CEC’s organizing the presidential elections and issued a positive report.

Summing up the political results of the elections, we can note that the Mongolian voters followed a “fashion for realism”, implying an emphasis on national interests, bordering on nationalism. This is the expert explanation for the victory of Haltmaagiin Battulgi – an athlete, artist and entrepreneur in one person. On the streets of Ulaanbaatar, Battulga was called “a real man” [6]. On one of Battulga’s banners carried the image of the president of the Russian Federation V.V. Putin, and the candidate himself met some members of the party “United Russia” during the election campaign. It is difficult to judge to what extent it helped him, but, according to Russian experts, “the vector for building partnership relations with Russia was drawn correctly”.

Image 6. In the election campaign, the future winner of the election Kh. Battulga used, among other things, the image of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Photo of one of the banners in Ulaanbaatar

The solemn inaugural ceremony was held on July 10, 2017 in the building of the State residence in the presence of deputies, the head of the Constitutional Court, other candidates and foreign diplomats. The official delegation of Russia was headed by presidential aide Igor Levitin. Official delegations from Japan and Singapore also arrived in Ulaanbaatar. The inauguration time was set at “the hour of the Horse” (a time interval from 11:40 to 13:40), which according to local belief is considered favourable.

After the Great State Khural approved the law on recognizing the elections valid, the new president Battulga, dressed in Daly (the national costume), uttered the words of the oath, placing his hand on the Constitution of the country: “I swear to respect and protect the sovereignty and the Constitution of Mongolia and faithfully execute the duties of the president.”

Image 7. Inauguration of President of Mongolia Kh.Battulga. In the photo: elected President Kh.Battulga and former President T.S.Elbegdorj after the ceremony of transfer of the state press

The first initiatives of the new president were accepted with some ambiguity. Thus, two weeks after the elections, Battulga appealed to civil servants and politicians, calling for the return of money from the offshore zone to the Mongolian bank “MongolBank”. However, no one responded, and the Mongolian state bank did not receive a single dollar. In addition, Battulga refused from the state residence and stayed in his house 400 meters from the administration to go to work on foot, but opposition politicians said that this was just a PR move [2]. In November 2017, President Battulga initiated the return of the death penalty, abolished in Mongolia in 2012.

But the most important decisions were to be taken later. Members of the Great State Khural discussed amendments to the Constitution concerning the powers of the president in wartime and his right to legislative initiative. On January 31, 2018, the Constitutional Court of Mongolia confirmed that the supreme state authority of Mongolia, which has the exclusive right to pass laws, is the Great State Khural, and the president’s power to approve legislation during wartime contradicts the Constitution.

In conclusion, I would like to note that electoral procedures in Mongolia do not have a sustainable development yet.

The political parties of Mongolia were created in different conditions. While the MPRP has a rich almost century-long history, other parties have formed only during the last decades. Moreover, the tradition of choosing a president from several candidates has not become customary in Mongolian society.

However, it should be pointed out that the replacement of political actors, political parties winning elections, contribute to the creation of a competitive political atmosphere. Therefore, Mongolia is now called a vivid example of political democratic transit [3; 9]. Despite the flaws this could be seen during the 2017 national elections.

Moreover, experts already agree that in general the elections in Mongolia are held in an atmosphere of openness and transparency, and the parliament serves as a filter against the concentration of influence in the hands of one person – the prime minister or president. As for the electoral system, the participation of only parliamentary parties’ nominees obviously puts them in unequal conditions. The legislation of Mongolia does not presuppose an opportunity for self-nomination or non-party candidates nomination, which adversely affects its political diversity.

Received 07.05.2018, revision received 14.07.2018.

References

- Batbayar Ts. Mongolia is New Identity and Security Dilemmas. – The Mongolian Journal of International Affairs. 2002. No. 8–9. P. 8.

- Fedorov P. Novyi prezident Mongolii dal 49 sutok vladel'tsam ofshornykh schetov, chtoby te vernuli den'gi na rodinu [The new President of Mongolia gave 49 days to the owners of offshore accounts to return the money home]. – Aartyk.ru. 14.08.2017. (In Russ.) URL: http://aartyk.ru/obshhestvo/novyj-prezident-mongolii-dal-49-sutok-vladelcam-ofshornyh-schetov-chtoby-te-vernuli-dengi-na-rodinu/ (accessed 12.02.2019). - http://aartyk.ru/obshhestvo/novyj-prezident-mongolii-dal-49-sutok-vladelcam-ofshornyh-schetov-chtoby-te-vernuli-dengi-na-rodinu/

- Golman M.I. Mongoliya. Demokraty snova u vlasti [Mongolia. Democrats in power again]. – Aziya i Afrika segodnya. 2013. No. 3. P. 11–16. (In Russ.)

- Kandidaty na post prezidenta Mongolii: skandaly i dostizheniya [Candidates for the post of the President of Mongolia: the scandals and achievements]. – REGNUM.RU. 05.05.2017. (In Russ.) URL: https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2272018.html (accessed 12.02.2019). - https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2272018.html

- Lishtovannyi E.I. Sovremennye geopoliticheskie tententsii i Mongoliya [Current geopolitical trends and Mongolia]. – Baikal'skii region i geopolitika Tsentral'noi Azii: Istoriya, sovremennost', perspektivy (materialy mezhdunarodnogo nauchnogo seminara-soveshchaniya) [Baikal region and geopolitics of Central Asia: history, modernity, prospects (materials of the international scientific seminar-meeting)]. Irkutsk: Ottisk. 2004. P. 48–50. (In Russ.)

- Mikhalev: Mongoliya. Pochemu imenno Battulga? [Mikhalev: Mongolia. Why precisely Battulga?] – Poveska dnya. 16.07.2017. (In Russ.) URL: http://agenda-u.org/news/mihalev-mongoliya-pochemu-imenno-battulga (accessed 12.02.2019). - http://agenda-u.org/news/mihalev-mongoliya-pochemu-imenno-battulga

- Mongoly, zhivushchie za rubezhom, progolosovali na vyborakh prezidenta [Mongols living abroad voted in presidential elections]. – REGNUM.RU. 13.06.2017. (In Russ.) URL: https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2287394.html (accessed 12.02.2019). - https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2287394.html

- Prezidentskie vybory v Mongolii: neozhidannyi itog predvaritel'nykh podschetov [Presidential elections in Mongolia: an unexpected result of preliminary calculations]. – REGNUM.RU. 26.06.2017. (In Russ.) URL: https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2293028.html (accessed 12.02.2019). - https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2293028.html

- Rodionov V. Politicheskii protsess v postsotsialisticheskoi Mongolii: formal'nye instituty i nefirmal'nye praktiki [Political process in post-socialist Mongolia: formal institutions and informal practices]. – Vlast. 2015. No. 2. P. 76–81. (In Russ.)

- Sosorbaram M. Nachalos'. Ganbaatar: my ne priznaem soobshcheniya TsIK [Begun. Ganbaatar: we do not accept the message of the CEC]. – Asiarussia. 27.06.2017. (In Russ.) URL: http://asiarussia.ru/news/16777/ (accessed 12.02.2019). - http://asiarussia.ru/news/16777/

- Sosorbaram M. U MNRP smenilsya kandiddat v prezidenty: vmesto N.Enkhbayara budet S.Ganbaatar [Have changed the MPRP presidential candidate: instead of N. Enkhbayar will S. Ganbaatar]. – Asiarussia. 17.05.2017. (In Russ.) URL: http://asiarussia.ru/news/16295/ (accessed 12.02.2019). - http://asiarussia.ru/news/16295/

- V Mongolii na vremya vyborov zapretili mitingi i prodazhu alkogolya [In Mongolia during the elections banned rallies and the sale of alcohol]. – REGNUM.RU. 23.06.2017. (In Russ.) URL: https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2292065.html (accessed 12.02.2019). - https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2292065.html

- V Mongolii naznachen vtoroi tur vyborov prezidenta [In Mongolia the second round of presidential elections is scheduled]. – REGNUM.RU. 26.06.2017. (In Russ.) URL: https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2293228.html (accessed 12.02.2019). - https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2293228.html

- V Mongolii pomenyali datu vtorogo tura prezidentskikh vyborov [Mongolia changed the date of the second round of presidential elections]. – REGNUM.RU. 28.06.2017. (In Russ.) URL: https://regnum.ru/news/2294019.html (accessed 12.02.2019). - https://regnum.ru/news/2294019.html

- Vybory prezidenta Mongolii: finishnaya pryamaya [Election of the President of Mongolia: finish line]. – REGNUM.RU. 26.06.2017. (In Russ.) URL: https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2292692.html (accessed 12.02.2019). - https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2292692.html

- Zheltov M. Mongoliya: sensatsionnaya pobeda oppozitsii ili rozhdenie dvukhpartiinoi sistemy? [Mongolia: sensational victory of the opposition or the birth of a two-party system?] – InterIzbirkom. 17.07.2016. (In Russ.) URL: http://izbircom.com/2016/07/17/монголия-сенсационная-победа-оппози/ (accessed 12.02.2019). - http://izbircom.com/2016/07/17/монголия-сенсационная-победа-оппози/