Changes in Federal Electoral Legislation in 2003-2024: Expert Assessment

Abstract

The paper presents the results of assessment of the modifications introduced to the electoral legislation since 2003, which was carried out by corresponding experts. The full list contained 170 novelties and was assessed by 42 experts. Another 15 experts assessed an abridged list of 45 novelties. The most unanimously assessed novelties related to the transparency (or lack thereof) of voting, exaggerated thresholds on the way of candidates to get on the ballot and on the way of parties to get into parliament. On many of the other novellas, opinions were quite varied. Nevertheless, the average assessments show that most of the novelties are evaluated negatively by experts. However, there were two short periods (2010-2012 and 2017-2018) when, according to experts, most of the novelties were aimed at improving the quality of elections.

Introduction

Since the adoption of the Federal Law "On Basic Guarantees of Electoral Rights and the Right to Participate in Referendums of Citizens of Russian Federation" No. 67-FZ of June 12, 2002, it has been amended 117 times (as of September 2024). Moreover, during this period, a new federal law on the election of deputies to the State Duma was adopted three times (in 2002, 2005 and 2014), while a law on the election of the President of the Russian Federation was adopted once (in 2003). These laws were also amended several dozen times (a chronology of changes in electoral legislation is available in [6]). In terms of the number of changes made, we counted the number of federal laws passed to amend the basic laws.

However, these figures still tell us little about actual changes in the electoral legislation. First, one law could contain a large number of amendments (examples are Federal Law No. 93-FZ of 21 June 2005 "On Amending Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation on Elections and Referendums and Other Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation", Federal Law No. 154-FZ of 23 May 2020 No. 154-FZ "On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation", Federal Law of 14 March 2022 No. 60-FZ "On Amending Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation"; Federal Law of 29 May 2023 No. 184-FZ "On Amending Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation"), while some laws contained only one amendment each. Second, the changes could be substantial, technical or terminological, and have no effect on the essential provisions and on citizens exercising their electoral rights. Third, the statistical data says nothing about what the modifications were directed at — whether they helped citizens to exercise electoral rights and contributed to democratic development of the country or, on the contrary, hindered it.

There are some published works that give assessments to the number of changes and modifications. For example, in [4] it is noted that "a total of 2,630 amendments have been made to Russia's electoral legislation over the last twenty-five years". However, we do not know how the authors of the paper considered the amendments, especially when it comes to the adoption of a new law (and the period specified by the authors of the paper includes the adoption of several new laws, including Federal Law No. 67-FZ of 12 June 2002). We believe that if we ignore technical and terminological changes and consider a set of amendments as a single amendment, the number of amendments would be an order of magnitude smaller.

Having analyzed the amendments introduced to the electoral legislation in 2003-2024, i.e. to the federal laws "On Basic Guarantees of Electoral Rights..." (without amendments that refer exclusively to the referendum), on the elections of deputies to the State Duma and the President of the Russian Federation, we counted 170 substantial amendments (all are listed in Table 1). Next, we set an objective: to determine and assess the focus of these changes with the help of election and electoral legislation experts.

Although existing works offer assertions that the entire period after 2000 (or after 2002) saw a decline in the democratic potential of the Russian electoral legislation (it is indirectly mentioned in the work cited above [4]), we believe that this is not quite true. In particular, it was noted [5] that during this long period of time there were many amendments focused on the opposite, that is, when a new amendment repealed the previous one and reinstated (at least partially) the one that was in force before the latter. Accordingly, while some of these amendments should be assessed negatively, amendments of the opposite nature should be assessed positively. A detailed analysis of many amendments can be found in [2; 3]. An attempt to quantify the evolution of Russian electoral legislation is made in [1].

In this paper, in order to assess the direction of changes in the electoral legislation and their effect on citizens exercising their electoral rights, we have presented a selection of 170 substantial amendments (full list) for expert judgment. Since this type of work requires much effort, we also gave the experts the opportunity to assess a smaller range of 50 amendments that are particularly significant (abridged list). Of these, 45 amendments correspond exactly to one of the amendments on the full list, and five combine two or three amendments each from the full list.

We proposed to assess the amendments on a five-point scale: -2 (significant deterioration of election quality), -1 (slight deterioration), 0 (neutral modification), +1 (slight improvement of election quality), +2 (significant improvement).

Experts

We reached out to 205 individuals we consider to be experts in elections and electoral legislation. We received responses from 57 experts, of which 42 responded to the full list and 15 responded to the abridged list.

Of these experts, there are 2 doctors of legal sciences, 9 candidates of legal sciences (one of these is also a doctor of historical sciences), 11 law graduates without a law degree (three of these are candidates of historical, philosophical or political sciences), one with incomplete higher education in law, 7 doctors of political sciences, 3 candidates of political sciences, one doctor of historical sciences, 3 candidates of historical sciences, one candidate of sociological sciences, and the other four experts have degrees in other fields of science.

In 2018, 31 experts addressed issues about desirable modifications to electoral legislation [7]. 29 experts write for the Electoral Politics journal. The experts include a current and two former deputies of the State Duma, two former chairs of election commissions of the constituent entities of the Russian Federation. Nine experts were members of the Scientific Expert Council of the CEC of Russia (SEC) in 2018-2020. Eight experts are included in the register of foreign agents.

Stanislav V. Andreichuk (Candidate of Historical Sciences), Maria S. Bainova (Candidate of Sociological Sciences), Grigory V. Belonuchkin, Ivan V. Bolshakov, Andrei Yu. Buzin (Candidate of legal sciences, member of the SEC), Nikolai I. Vorobyev (Candidate of Legal Sciences, chairof the Tambov Oblast Election Commission 1993-2003, SEC member), Vladimir Ya. Gelman (Candidate of Political Sciences), Irina M. Gertsik (lawyer), Georgy M. Globin (Candidate of Technical Sciences), Aleksandr V. Grezev, Pavel V. Dubravskiy (incomplete higher education in law), Roman V. Evstifeev (Doctor of Political Sciences), Sergei V. Zhavoronkov, Sofiya Yu. Ivanova (foreign agent), David N. Kankiya (foreign agent), Konstantin V. Kiselev (lawyer, Candidate of Philosophical Sciences), Artem A. Klyga (lawyer), Vitalii S. Kovin (Candidate of Historical Sciences, SEC member, foreign agent), Yurii G. Korgunyuk (Doctor of Political Sciences), Irina Kh. Kusova (Candidate of Historical Sciences), Yelena A. Lukyanova (Doctor of Legal Sciences, NEC member, foreign agent), Viktor I. Lysov, Arkadii E. Lyubarev (Candidate of Legal Sciences, SEC member), Aleksei V. Mazur, Mikhail Yu. Martynov (Doctor of Political Sciences), Valentin V. Mikhailov (Doctor of Historical Sciences, deputy to the State Duma in 1994-1995), Galina M. Michaleva (Doctor of Political Sciences), Oksana S. Morozova (Candidate of Political Sciences), Aleksander A. Pozhalov (SEC member), Andrei E. Pomazansky (Candidate of Legal Sciences), Yevgeny N. Poroshin (lawyer), Yelena L. Rusakova, Aleksei V. Rybin (lawyer), Yekaterina Ye. Skosarenko (Candidate of Legal Sciences), Andrei D. Suvorov (lawyer), Mikhail V. Titov (lawyer, chair of the Tver Oblast Election Commission in 1997-2007), Yevgeny V. Fedin, Dmitry M. Khudoley (Candidate of Legal Sciences), Ilya G. Shablinsky (Doctor of Legal Sciences, SEC member, foreign agent), Lyudmila V. Shapiro (Candidate of Chemical Sciences), Lev M. Shlosberg (foreign agent), Ivan A. Shukshin.

The experts who assessed the abridged list are Mikhail I. Amosov (Candidate of Geographical Sciences), Leonid G. Berlyavsky (Candidate of Legal Sciences, Doctor of Historical Sciences), Grigory V. Golosov (Doctor of Political Sciences, SEC member), Aleksei S. Kassian (Doctor of Phylological Sciences), Yelena V. Makei (lawyer), Ekaterina P. Marmilova (lawyer, Candidate of Historical Sciences), Yuli A. Nisnevich (Doctor of Political Sciences, deputy to the State Duma in 1993-1995), Igor Yu. Okunev (Candidate of Political Sciences), Aleksei V. Petrov (lawyer, Candidate of Political Sciences, foreign agents), Stanislaw Z. Raczynski (lawyer, SEC member), Pavel B. Salin (Candidate of Legal Sciences), Yuri P. Sinelshchikov (Candidate of Legal Sciences, deputy to the State Duma), Mikhail S. Tikhonov (foreign agent), Anton V. Sheinin, Stanislav N. Shkel (Doctor of Political Sciences).

Results

Table 1 shows the minimum, average, and maximum scores for each modification from the full list, as well as the number of positive, zero, and negative scores. This table also includes responses to the 45 questions from the abridged list (i.e., without the five rows that combined several modifications). The table also shows the number of responses (not all experts assessed all modifications).

Table 1. Analyzed changes in the electoral legislation and their assessment

| Law | Modification | Number of assessments | Analysis of assessments | |||||||

| total | pos | zeros | neg | min | avg | max | polarization | |||

| No. 19-FZ of 10 Jan 2003 | In the presidential election, the size of the action group is increased from 100 to 500 people | 56* | 2 | 13 | 41 | -2 | -0.95 | 2 | 0.04 | |

| No. 19-FZ of 10 Jan 2003 | In the presidential election, the number of required signatures in support of nomination is increased from one million to two million | 57* | 2 | 2 | 53 | -2 | -1.65 | 2 | 0.04 | |

| No. 19-FZ of 10 Jan 2003 | In the presidential election, political parties and electoral blocs that nominated candidates are provided with free airtime and free print space in addition to the free airtime and free print space provided to the candidates themselves | 42 | 25 | 8 | 9 | -2 | 0.52 | 2 | 0.29 | |

| No. 97-FZ of 04 Jul 2003 | Public associations are prohibited from joining electoral blocs | 42 | 1 | 3 | 38 | -2 | -1.33 | 1 | 0.02 | |

| No. 102-FZ of 04 Jul 2003 | More possibilities for forming constituencies with large deviations in the number of voters from the average representation norm | 40 | 0 | 11 | 29 | -2 | -1.03 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| No. 99-FZ of 12 Aug 2004 | The option to change the terms of office of elected bodies in order to combine elections is introduced | 42 | 3 | 20 | 19 | -2 | -0.55 | 1 | 0.08 | |

| No. 122-FZ of 22 Aug 2004 | Election commissions are banned from taking loans for holding elections | 41 | 8 | 27 | 6 | -2 | 0.07 | 2 | 0.26 | |

| No. 159-FZ of 11 Dec 2004 | The practice of electing heads of administrations of federal subjects is overturned | 57* | 0 | 1 | 56 | -2 | -1.95 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| No. 51-FZ of 18 May 2005 | A fully proportional representation system is introduced for the State Duma election | 57* | 8 | 9 | 40 | -2 | -0.88 | 2 | 0.17 | |

| No. 51-FZ of 18 May 2005 | The threshold for the State Duma election is increased to 7% | 57* | 1 | 2 | 54 | -2 | -1.74 | 1 | 0.02 | |

| No. 51-FZ of 18 May 2005 | Minimum number of regional groups in State Duma election is increased from 7 to 100 | 42 | 1 | 6 | 35 | -2 | -1.36 | 1 | 0.02 | |

| No. 51-FZ of 18 May 2005 | The maximum size of the core part of the candidate list for State Duma election is reduced from 18 to 3. | 42 | 13 | 15 | 14 | -2 | -0.12 | 2 | 0.60 | |

| No. 51-FZ of 18 May 2005 | Sanctions for refusing a seat in the State Duma election are abolished | 55* | 4 | 14 | 37 | -2 | -0.91 | 2 | 0.08 | |

| No. 51-FZ of 18 May 2005 | The State Duma election provide for the possibility for regional branches of political parties to create their own election funds; taking this into account, the total maximum amount of funds to be spent by a party is increased by about 9 times. | 41 | 24 | 11 | 6 | -2 | 0.56 | 2 | 0.18 | |

| No. 51-FZ of 18 May 2005 | If a party refuses to participate in a debate, the total debate time is reduced and the party gets its share of time for individual campaigning | 42 | 4 | 16 | 22 | -2 | -0.48 | 2 | 0.11 | |

| No. 93-FZ of 21 Jun 2005 | Electoral blocs are abolished | 57* | 2 | 5 | 50 | -2 | -1.56 | 1 | 0.04 | |

| No. 93-FZ of 21 Jun 2005 | Two single annual voting days (second Sunday in March and second Sunday in October) are introduced | 57* | 17 | 11 | 29 | -2 | -0.35 | 2 | 0.47 | |

| No. 93-FZ of 21 Jun 2005 | The maximum possible barrier to the election of deputies to the legislative bodies of the federal subjects is set to 7% | 42 | 4 | 6 | 32 | -2 | -1.21 | 2 | 0.11 | |

The table is not fully displayed Show table

* Asterisk indicates modifications included not only in the full list but also in the abridged one.

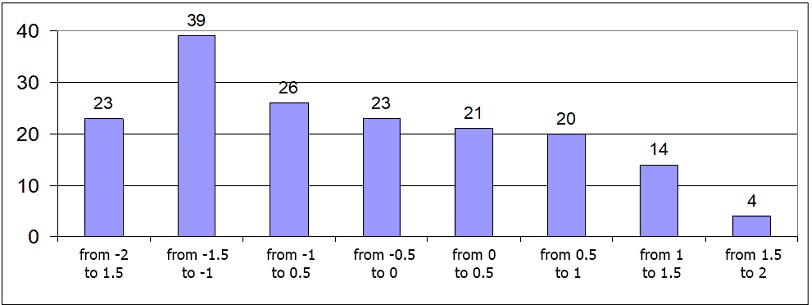

The table demonstrates that the assessments are quite varied. Mean scores ranged from ‑1.95 to 1.67. 59 amendments received a positive average rating, 110 received a negative average rating, and one amendment ("The law of federal subject may provide for the appointment of observers by the public chamber") had an average rating of 0. The distribution of scores over half-unit intervals is demonstrated in Figure 1. Most assessments fell between -1.5 and -1 (39) and between -1 and -0.5 (26). As a result, we can see that the prevalent assessments are negative.

Figure 1. Histogram of average scores by value intervals

The lowest score (-1.95) was given to the abolition of gubernatorial elections (2004). The three modifications with the lowest scores were also the abolition of the right of public associations to send observers (2005, -1.82) and the abolition of the option to appoint members with consultative capacity to CoECs, TECs and PECs (2022, -1.80).

It is also worth noting seven modifications that received a negative assessment from all experts. These include, besides the abolition of gubernatorial elections and commission members with consultative capacity: expanded options of forming constituencies with large deviations (2003); the abolition of the obligation for public office candidates to go on vacation (2005); expanded options for voting outside the voting premises (May 2020) and, two months later, a similar provision on voting in places "suitable for voting equipment" (July 2020); the authorization not to include candidate information on the ballot, and last names of candidates when voting for lists (2021).

The highest score (1.67) was given to the option of installing video surveillance cameras in polling stations (2016). The removal of observers only by court (2016; 1.59) and the reduction of the required number of signatures in presidential elections (2012; 1.56) were also among the three modifications with the highest scores.

Ten modifications were received positive assessments from all the experts. In addition to the novelty of removing observers by court: the 2010 novelty on the mandatory seat allocation by the list that passed the threshold; additional measures against abuse of absentee ballots (2010); reduced number of regional groups in Duma elections from 80 to 70 (2011); additional guarantees for suffrage of persons with disabilities (2011); reduced threshold of 5% to the Duma elections (2011) and similar reductions for the rest of the elections (2014); permission not to open a special account for elections in rural settlements (2014) and expansion of such options (2018); and installation of video surveillance cameras in TECs (2017).

In general, the focus of the expert assessments is clear. To the greatest extent, experts support the novelties that expand election control and reduce thresholds to electoral rights being exercized, and to the greatest extent condemn the novelties that promote the opposite.

At the same time, quite a few novelties were rated close to neutral: 44 averaged between -0.5 and 0.5 in rating. There are two possible reasons here: the polarity of assessments, giving an average neutral score, and the opinion of the majority of experts about the low impact of the novelty on the circumstances. To determine the second reason, we checked what proportion of experts gave some or other of the novelties the rating of zero.

It turned out that only 14 novelties had a proportion of zero ratings greater than half. Moving the presidential election to the third Sunday in March (2016) received the most zero ratings (79%). Second place (66%) went to the ban on taking loans for election commissions (2004), and third place (64%) to the right to appoint observers by public chambers in regional (2018) elections.

At the same time, six novelties received no zero ratings at all, being assessed as either positive or negative. These include: abolishing the right of public associations to send observers (2005); the right to cancel direct gubernatorial elections (2013); making it more difficult to challenge vote returns in court (2014); reducing the allowed share of defective voter signatures in regional and municipal elections from 10 to 5% (2020); allowing three-day voting (2020); prohibiting citizens included in the register of foreign agents and/or in the unified register of information on persons involved in the activities of extremist or terrorist organizations from being observers, authorized representatives of candidates and electoral associations, and proxies (2024).

We tried to estimate the degree of polarization of evaluations using the following formula: the ratio of of positive ratings to the number of negative ratings or vice versa (the smaller number was divided by the larger one) multiplied by the total share of positive and negative ratings. The resulting coefficient can have values from 0 to 1 (the indicator is also included in Table 1). If all experts give only positive ratings, or only negative ratings, or only 0, the coefficient will take the value 0. If there are no zero ratings and the number of positive and negative ratings is equal, the coefficient will take the value 1. The fewer zero ratings there are, the more polarization there will be. The closer the number of positive ratings is to the number of negative ratings, the greater the polarization will also be.

The maximum value (60%) was obtained by reducing the maximum of the core part of the list at the State Duma elections from 18 to 3 (2005; 13 positive ratings, 15 zero, 14 negative). In second place (57%) is the option to replace a member of an election commission with a deciding vote by the party that nominated him/her (2020). In third place (52%) is the abolition of mandatory use of the proportional representation system in municipal elections. We also checked whether there are differences between novelties on the abridged list and those included only in the full list, and it turns out that there is no difference: novelties on the abridged list have an average polarization of 15%, while the rest of the novelties have an average polarization of 13%.

Differences in assessments

For brevity, all experts can be divided into lawyers, political scientists and the others. We considered experts with a higher education in law (including incomplete) and/or a degree in law to be lawyers. Among those who responded to the full list they amounted to 16 and to 7 among those who responded to the abridged list. Experts carrying a degree in political, historical or social sciences qualified as political scientists: there were 11 and 4 of them among those who responded to the full and abridged lists, respectively. The remaining 15 experts who responded to the full list and 4 who responded to the abridged list.

For each category, we calculated average scores for each modification. Results for most issues did not differ significantly. For example, in the pair lawyers/political scientists the difference in the module exceeded 0.5 only for 34 modifications out of 170 (20%). That said, there was no uniform trend. Lawyers gave higher scores to 74 modifications and lower scores to 95 (for modifications exceeding a modulus of 0.5, 13 and 21 respectively). The largest difference manifested for the novelty "Voting at current location" (0.86 for lawyers, -0.13 for political scientists). The largest difference of the reversed kind manifested for the novelty "Constituencies are established for 10 years" (-0.13 for lawyers, 0.82 for political scientists). In total, in 16 cases (9%) the assessments of lawyers and political scientists contrasted each other.

In the lawyer/others pair, the modulus difference exceeded 0.5 for only 28 modifications (16%). Lawyers gave higher scores more often: in total, they gave higher scores to 97 modifications and lower scores to 65 (but for modifications greater than modulo 0.5, the number is 14 for both lower and higher). The biggest difference manifested for abolition of election commissions of municipal entities (-1.75 for lawyers, ‑0.40 for others). The largest difference of the reversed kind manifested for the novelty "Citizens involved in the activities of an organization in respect of which a court decision on liquidation or prohibition of activities on grounds related to extremist activity or terrorism has entered into force are deprived of passive suffrage" (-0.82 for lawyers, -1.74 for others). The scores of 12 novelties (7%) were opposite.

In the political scientists/others pair, the modulus difference exceeded 0.5 for only 34 modifications (20%). Political scientists also gave higher scores more often: they gave higher scores to 107 modifications in total, and lower scores to 63 (for modifications greater than modulo 0.5, 27 and 7 respectively). The largest difference manifested for the prohibition to use images of individuals who are not candidates (0.00 for political scientists, ‑1.00 for others). The largest difference of the reversed kind manifested for the novelty on "consolation" seats in the Duma elections (-0.45 for political scientists, 0.53 for the others). The scores of 10 novelties (6%) were opposite.

Some difference was also observed in the assessments of the experts who responded to the full and abridged lists. In four (9%) out of 45 cases the assessments were opposite (two single voting days in a year; abolition of early voting in municipal elections; obligation of a candidate to report information about foreign property and close accounts in foreign banks; option to replace a member of the election commission with a deciding vote by the party that nominated him/her).

There was no uniform trend here either. Experts who responded to the full list gave higher scores in 15 cases and lower scores in 30 cases. However, the difference of over 0.5 modulo manifested only for 13 cases (29%), when the experts who responded to the full list gave lower scores. The biggest difference manifested for the novelty of remote e-voting (-1.57 for experts who responded to the full list; -0.60 for experts who responded to the abridged list).

We also did separate calculations of average scores for the eight experts included in the foreign agents register and compared these scores to the average scores of all experts. The calculations revealed no significant difference. "Foreign agents" gave an opposite assessment only for 10 modifications (6%). The difference exceeding modulo 0.5 manifested for 29 modifications (17%; "foreign agents" gave lower scores in 22 cases and higher scores in 7). In total, "foreign agents" gave lower scores in 102 cases and higher scores in 63 cases.

The biggest difference in the assessments of "foreign agents" manifested for the novelty "Nomination in a single-seat (multi-seat) constituency of more candidates than the number of deputy seats shall be grounds for exclusion from the list of all candidates nominated in the given constituency, but not for refusal to certify the list", which implemented the decision of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation (the average score was 0.11 for all experts and 1.33 for "foreign agents"). The largest difference of the reversed kind manifested for two novelties: the submission of observer lists at least three days before election day (average score of -1.05 from all experts; -2.0 from "foreign agents") and the exemption from collecting signatures in State Duma elections for parties elected to regional parliaments (average score of 0.95 from all experts; 0.0 from "foreign agents").

Distribution of grades by year

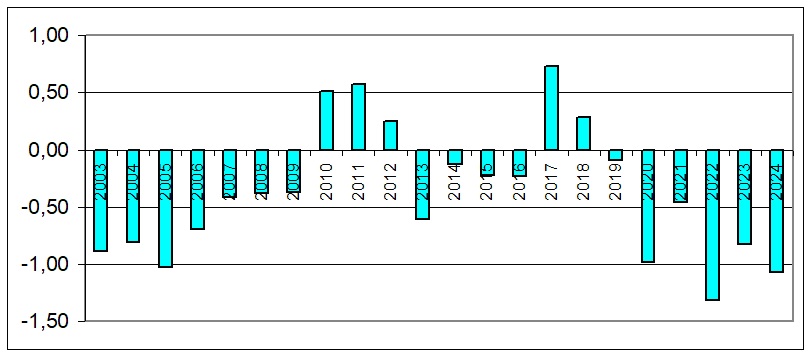

It is not difficult to see that novelties from different years were evaluated differently by experts. Figure 2 shows the average scores by year. As we can see, there were only two periods when the annual average scores had positive values.

Figure 2. Average assessment by year

The first period is 2010-2012. At this time, a number of laws were adopted that implemented the proposals made in the messages to the Federal Assembly by President Dmitry Medvedev. The first such proposals were made in the 2008 message and implemented in 2009. However, four of the seven significant novelties from 2009 were assessed negatively by experts: first of all, the abolition of the electoral deposit and the abolition of the right of public associations to nominate lists of candidates in municipal elections (the first was initiated by the regional parliament but was supported by the president, the second was proposed by deputies and clearly went against the president's pronouncements). Besides, the three novelties that were rated favorably received mostly low scores.

The situation is different for the 2010 novelties: seven out of eight were rated positively. These novelties appeared after the walkout of the three opposition factions, and were mainly aimed at protecting the opposition and weakening the administrative resource, which was running too much unchecked at that point. This trend continued in 2011.

Some of the 2012 novelties were a reaction to the protest wave and were democratically oriented, but then the opposite trend started to emerge. Nevertheless, 7 out of 10 novelties from that year received favorable assessments. The 2013-2016 novelties were already largely aimed at restricting voting rights and it is not surprising that they earned mostly negative assessments.

The second positive period relates to 2017 and 2018. It is connected with the legislative activity of the reformed CEC of Russia and the new leadership in the domestic policy domain of the presidential administration and their desire to make the elections more legitimate. As we can see, seven out of the nine significant novelties from these two years received positive ratings on average, one received zero and another close to zero (-0.02). But the trend of legitimacy being sacrificed to "manageability" has prevailed again as soon as 2019.

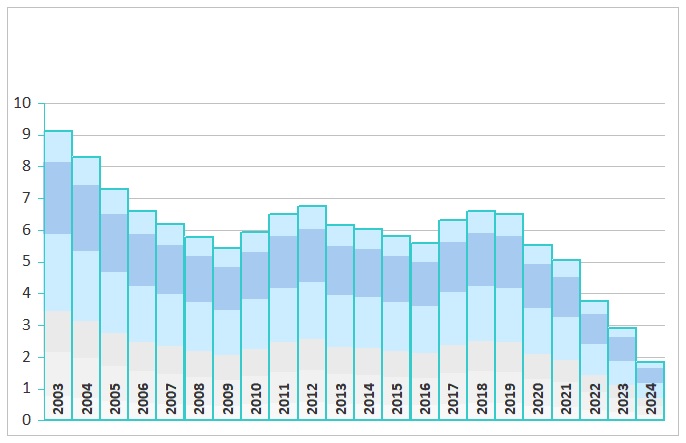

Figure 3 clearly shows the change in the quality of Russia's electoral legislation. If we take the level of legislation quality when it was passed in 2002 as 10, and assume that it changes each year by the average scores given to the novelties by our experts, we get a level of 1.94 by September 2024.

Figure 3. Expert assessment of the quality of electoral legislation. The baseline (2002) is taken as 10. Modifications in each year correspond to the average expert assessment

Conclusion

The main question of survey research pieces is how objective the results obtained are, how much they depend on the selection of experts. Our piece is no exception.

First of all, it is important to understand that we sought to evaluate the novelties of the electoral legislation on the basis of the principles of people's power and ensuring the electoral rights of citizens as laid down in the Russian Constitution. The experts were selected from among those who adhere to these principles. It is not hard to imagine that, having picked experts from among the adherents of "sovereign democracy", other researchers will get different assessments.

It was also important to us that the experts had different backgrounds in elections and electoral law. Our experts include both academic lawyers and political scientists (although they also have practical electoral experience) and people with extensive practical experience: either as members of election commissions or as candidates, election staff, political technologists, observers and observation organizers, electoral statistics experts.

What do our findings tell us? There was a fair degree of unanimity among such a large and diverse group of experts on individual novelties. These are precisely the issues that concern the transparency (or lack thereof) of voting, exaggerated thresholds on the way of candidates to get on the ballot and on the way of parties to get into parliament. For many other novelties, the range of opinions was quite varied, and these are the issues where the focus is more difficult to assess and with which experts meet less often in their practice.

One of the experts wrote to us that he had to solve a dilemma on a number of issues: should he assess the intention of the legislator and the feasibility of the given measure at that point in time, or the actual (including delayed but anticipated) consequences of the motion and the enforcement of the set of regulations? When setting the task to the experts, we made it quite clear that they should assess the impact of the adopted novelty on the elections. But it is easy to see that for many experts it was easier to assess the novelty per se, without analyzing its implications. This is where the differences in grades come from as well.

Nevertheless, we can see that the results turned out to be quite substantial. The dynamics of divergent modifications in particular is well reflected in the expert assessments. The highlights are the two short periods (2010-2012 and 2017-2018), when most of the novelties were aimed at democratization of elections. This can be considered as additional evidence that the majority of our experts do not seek to indiscriminately reject all proposals coming from the Russian government, that they are capable of positively assessing proposals designed to protect democratic principles and the electoral rights of citizens.

Received 13.10.2024, revision received 22.10.2024.

References

- Buzin A.Yu. Vzlyot i padeniye rossiyskogo izbiratelnogo zakonodatelstva [The Rise and Fall of Russian Electoral Legislation]. Berlin: Friedrich Ebert Foundation, 2024. (In Russ.)

- Kynev A.V., Lyubarev A.E. Partii i vybory v Rossii 2008–2022: Istoriya zakata [Parties and Elections in Russia 2008-2022: A History of the Decline]. Moscow: Novoye literaturnoye obozreniye, 2024. 488 p. (In Russ.)

- Kynev A.V., Lyubarev A.E. Partii i vybory v sovremennoi Rossii: Evolutsiya i devolutsiya [Parties and Elections in Modern Russia: Evolution and Devolution]. Moscow: Fond “Liberalnaya missiya”. 2011. 792 p. (In Russ.)

- Lukyanova Ye.A., Poroshin Ye.N., Arutyunov A.A., Shpilkin S.A., Zvorykina Ye.V. Vybory strogogo rezhima: Kak rossiiskiye vybory stali nevyborami i cho s etim delat? Politichesko-pravovoye issledovaniye s elementami matematiki. [Maximum Security Elections: How Did Elections in Russia Turn Into Non-Elections and What is to Be Done About It? A Political and Legal Research With Elements of Mathematics]. Moscow: Mysl, 2022. 400 p. (In Russ.)

- Lyubarev A.E. Kak izbiratelnoye zakonodatelstvo vliyayet na vybory: analiz 35-letnei rossiyskoi istorii [How electoral legislation affects election: an analysis of 35 years of Russian history]. – Comparative Constitutional Review. 2023. No. 3. P. 150-170. DOI: 10.21128/1812-7126-2023-3-150-170. (In Russ.)

- Lyubarev A.E. Khronologiya izmeneniy rossiyskogo izbiratelnogo zakonodatelstva, 1988-2024 [A Timeline of Modifications in Russian Electoral Legislation, 1988-2024]. – Website of the Independent Institute of Elections. URL: http://vibory.ru/analyt/chron.htm (accessed 04.10.2024). (In Russ.) - http://vibory.ru/analyt/chron.htm

- Lyubarev A. Na puti k reforme zakonodatelstva o vyborakh: pozitsiya ekspertov [On the way to reforming the electoral legislation: An expert take]. Moscow: Izdatelskiye resheniya. 2019. 242 p. (In Russ.)