A Study of the 2024 Presidential Election Using Electoral Cleavage and Political Dimension Theory

Abstract

The paper examines the outcome of the 2024 presidential election through the lens of electoral cleavage and political dimension theories. The basic principle in this case is as follows: to qualify as one, an election should at the very least indicate a significant correlation between electoral cleavages and opposing candidates in the political space. The author concludes that despite the general abnormality of the situation, the election results follow an understandable political logic and are not a product of pure fraud. Putin's abnormally high result was ensured by purposeful work of the entire state apparatus. However, to a greater extent, this result was ensured by voters having been given a limited choice and by the most favourable and unfavourable conditions having been created for the incumbent and his "competitors", respectively. The author assumes there were a number of regions where ballot stuffing took place in favor of Slutsky: in St. Petersburg and Nenets Autonomous Okrug specifically, and likely in Bryansk, Vologda, Kursk and Tyumen Oblasts as well. At the same time, the ballot stuffing is described as a series of isolated events that had no effect on the general state of affairs: if the goal was to carry the LDPR leader to the second place, it was not met. The author also points out a disruption of a previous trend, where the incumbent's main political rival came from the opposition on the conservative left. The 2024 presidential election was the first time when Putin was opposed not by social conservatives, but by a liberal candidate and a "dove" (albeit a very moderate one). In the second major political dimension, which imbued the first electoral cleavage, it was Davankov, not Kharitonov or Slutsky, who stood opposite Putin. The socio-economic sub-dimension — incumbent vs. Kharitonov and Slutsky — imbued the first EC in nine cases and the second in six. All other cases were oppositions between Putin and Davankov.

Today, elections are an integral element of the political design of the vast majority of countries. This does not come as a surprise, since these countries are republics at least formally, and their constitutions are based on the concept of popular sovereignty. The mechanism for legitimizing power in republics is regular elections. Even where the republic is only a fiction, it is impossible to abandon the elections, at least as a ritual. That is why elections were held in Stalin's USSR, in Maoist China, and under all the Kims in the DPRK.

Naturally, the state and the substance of elections as an institution in countries with different regimes vary widely on the scale of "authoritarian–democratic". In some countries, elections are held only for imitation. In others, they are a real mechanism for forming power and determining the national course. There are also bizarre combinations of authoritarian and democratic practices.

Our country has known the institution of elections for over a century. Its history has seen periods of purely ritualistic elections as well as those that could be called real ones. Over the past couple of decades, Russia has systematically drifted toward authoritarianism, and today there is reason enough to consider it an electoral autocracy [5]. There has been many works covering the practices of domestic electoral authoritarianism, and a kind of summary can be found in a book whose title starts with the words "How did elections in Russia turn into non-elections" [13]. But to what extent does this rhetorical device reflect the reality of the situation?

From an electoral point of view, today's Russia is not just sick, but teetering on the brink between life and death. And just like in the medical profession there is an ongoing dispute over considering an organism still alive or already dead, so does political science maintain interest in whether there is any semblance of election in today's Russia or not.

From the medical point of view, an organism is considered alive if it reproduces at least some processes of self-regulation. Have elections in the newest Russia, particularly the presidential election of 2024, shown any signs of life? Judging by the diligence with which the authorities kept away undesirable candidates and created obstacles to observation, certain signs of life were definitely there. However, what is the situation really like?

Electoral cleavage theory in particular can help to answer this question — or rather, its modification that studies elections as an indicator of the state of mass political consciousness. From the theory standpoint, the presence of a stable significant correlation between electoral cleavages (formed by territorial differences in voting) and oppositions between players (candidates, parties) in the political space indicates that elections continue to exist in fits and starts (even if those fits and starts are extremely faint). If this connection is not observed, then the patient is more likely to be dead than alive.

Electoral cleavage theory and political dimension theory

Before proceeding the results of the study, let us determine the terms used.

Existing publications on cleavages contain many missing pieces and contradictions. One and the same notion is often used to denote different things. By using the same terms, authors often discuss unrelated processes and phenomena.

In its classical version [12], the cleavage theory explains the evolution of party systems in Northwestern Europe through the following social interest conflicts that reproduced themselves over decades and centuries: 1) between center and periphery (capital and regional elites); 2) state and church (religious and secular voters); 3) rural land and urban industry ("village" and "city"); 4) owners and workers.

This theory almost entirely focused on the social side of the process, and the issue of the political content of the cleavages was essentially left unattended, also due to methodological difficulties. In particular, S.Lipset and S.Rokkan refrained from equating the cleavage between employers and employees with the political opposition between opponents and supporters of socialism, likely because it only appeared this way from the socialist perspective. From the opposite perspective, particularly that of liberals and liberal conservatives, it was seen as an opposition between supporters and opponents of democracy (and socialists and communists had multiple other opponents).

The understanding of cleavages as social conflicts (or at least differences) is still dominant among American researchers [6], while the attention of Europeans has gradually shifted from social to political sphere. Lipset and Rokkan's schematic conceptualization largely contributed to the shift, since, to a certain extent, they viewed the subject as if from above and overlooked many "irrelevant" details.

In particular, the hypothesis of "frozen party systems", which suggested that the introduction of universal suffrage in Europe in the 1920s froze the development of party systems until the 1960s, seems convincing only if we ignore World War II and the political perturbations associated with it. In the Europe of 1930s and 1940s, nothing was even close to "freezing". A more proper statement would be that Europe fell back a century, and then took a long time to recover from the shock and in the 60s, in fact, it barely reached the state it was in forty years before.

As a matter of fact, one of the weaknesses of Lipset and Rokkan's concept is the attempt to explain political processes by relying on endogenous factors alone, since said processes are largely conditioned by exogenous factors, including foreign policy. For example, the mid-2010s immigration crisis in Europe, which gave rise to a wave of right-wing populism, had nothing to do with the domestic policy of Europe's countries. Situations like these are not the exception, but rather the rule: at the very least history has evidence of numerous empires collapsing under the pressure of "barbarians".

The connection between social and political structures and processes is quite indirect and even convoluted. This has always been obvious, otherwise science would not have split into social and political. Still, the split did not prevent the concepts from both spheres being conflated. For example, the term "cleavage" has been used both in social and political science, giving rise to such the notion of "political cleavage" in particular [4; 15; 17; 18].

To reiterate, the "social" and "political" cleavages are related in an indirect manner, and there is no spontaneous mutual influence between them. As we have already pointed out earlier, "political" cleavages are much more mobile and unstable than "social" cleavages [7]. These two phenomena exist as if in different time streams. In a sense, "social" and "political" cleavages can be compared to terrain and rivers, respectively. The landscape largely determines the river's character, creating a cascading mountain waterfall or a lowland stream, but its influence on the amount of water in the waterway is largely indirect. For example, in a drought, both mountain and lowland steams become shallow and dry. Naturally, the river is capable of affecting the landscape as well, but nowhere near as much as, for example, tectonic plate shifts.

Perhaps it is precisely because of the complexities in the relationship between political and social processes that, since the 1970s, political oppositions in Europe have been studied in the context of "issue dimensions" (and, in fact, political dimensions) theory rather than the cleavage concept. It all started with the "Manifesto" project, whose authors' choice of subject was the issues (questions) of the election platforms and programs of political parties. By and large, it would be more correct to call "political cleavages" "political dimensions," but this typology was largely thwarted by the project participants themselves, who, at a certain stage, refused to calculate the dimensionality of the political space.

At first, factor analysis was used to identify "issue dimensions" [3]. However after the results appeared unsatisfactory (including because of the revealed mismatch between political dimensions and "social" cleavages), factor analysis was abandoned, and a methodology that fit party positions into a single "right-left" cleavage was proposed instead [2] (for details, see [8; 10]). The term "issue dimensions" came to mean, in essence, the issue domains to which certain agenda items belonged.

The literature on "political cleavages," however, interpreted the latter not as issue domains, but as dimensions that occupy orthogonal positions to the dominant "right-left" cleavage, which is socio-economic at its core.

However, this paper uses the term "political dimensions" to denote political oppositions, while "cleavage" denotes so-called electoral cleavages, which are revealed by factor analysis of territorial differences in voting. Being almost as fluid and changeable as political dimensions, ECs cannot be considered an equivalent of Lipset and Rokkan's "social" cleavages. Still, we should keep in mind that in its "classical" format the cleavage concept is largely based on conjecture and general considerations rather than on definitive calculations. The attempt to apply such reasoning in empirical analysis most often meets "material resistance", since reality is much more diverse and elusive than the definitions one tries to customize it to.

There two advantages to the concept of "electoral cleavage": 1. such cleavages are revealed in a purely empirical way, through factor analysis of vote returns for different parties (candidates) in different territorial units; 2. the existing methods help reveal (if any) political interpretation of the EC and links with the electorate's social structure.

Problem statement

This paper describes the electoral cleavage in the 2024 presidential election, the political interpretation of ECs and how much it has changed since previous elections. At the same time, we tried to establish whether this method could help to detect ballot box stuffing for certain candidates.

Let it be known before anything else that we first of all concerned ourselves with ballot box stuffing for Leonid Slutsky (LDPR leader) and not so much for the incumbent. Goals being scored in favor of Vladimir Putin is an open secret; it is much more interesting to find out what conditioned the vote for him in the first place — ballot box stuffing or actual lack of choice.

Leonid Slutsky's case requires different wording: whether or not ballot box stuffing in his favor took place at all, and if it did, then on what scale. The fact is that Slutsky is the only candidate that is interesting enough for the election organizers to add votes for. It was important that Putin's main "competitor" did not become a "candidate for peace", a role in which New People candidate Vladislav Davankov found himself against his will. The CPRF candidate Nikolai Kharitonov was not a threat in this respect, but the government had no reason to play up to the Communists. They were always tolerated, but never liked — at least not enough to allow them to earn any extra points.

Slutsky, who after Vladimir Zhirinovsky's death made LDPR into the discount United Russia, was much more convenient in this capacity. Zhirinovsky was more flexible and inventive, managing to intercept from the CPRF the votes that would not have gone to the "party of power" in any case. One could equate a vote for Slutsky to the support for the state's policy and anything it entails, but a more loud-mouthed kind of support.

The election results were analyzed at three levels: federal subjects, territorial election commissions and precinct election commissions. At the federal subject and TEC levels, the entire data set was subjected to factor analysis, while PEC data were analyzed by region (to avoid equivalence with the mean value).

In this effort to maximize the incumbent's results, the calculations are done not only on the entire data set, but also on the populations distinguished by cut-off points within the normal distribution.

Let us clarify. According to S.Shpilkin (recognized as a foreign agent by the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation), the graph of the normal distribution of turnout at elections should resemble a Gaussian bell curve — with a peak close to the mean value and side tending to zero [16]; the presence of several "humps" in the normal distribution is an obvious sign of administrative efforts to "inflate" the turnout and the incumbent's result. We hold a similar view.

Therefore, we made two cut-offs: the first at the bottom point following one of the first "humps", the second at the bottom point before one of the last "humps". How come there is no need to make cut-offs before the very last and after the very first "hump"? Everything depends on the number of PECs in the cut-off set: if it is insignificant, cutting off the last "hump" will yield the number of precinct commissions not too different from the entire set, while cutting off all the "humps" following the first one will give an insufficient number of cases for analysis.

The next step was to compare the structure of electoral cleavages in three different sets. A significant difference may indicate ballot stuffing in favor of certain candidates. Such cases were analyzed after comparing electoral cleavages with political oppositions (dimensions), identified through factor analysis of candidates' positions on the issues of the current political agenda.

Research methodology

As we mentioned before, factor analysis (principal component method) was the main method for identifying electoral cleavages and political dimensions.

Factor analysis of the share of votes cast in different territorial units for different candidates allows us to identify electoral cleavages, which also act as factors of territorial differences in voting. Factor analysis shows which candidates' results change in tune from territory to territory and which candidates' results change in counter-phase, thus highlighting the main patterns of their opposition. Moreover, the second and third order links are recorded along with the most obvious ones that can be detected by correlation analysis.

The factor analysis of the candidates' positions on the issues of the current political agenda allows us to structure the numerous oppositions on individual items to a set of compact patterns, which, as a rule, are characterized by the greatest polarization of positions.

The selection of issues for analysis and rating of candidates' positions was carried out according to the methodology of the project "Russia's Current Political Agenda in Inter-Party Discussion" [1].

The main criterion of selection is the polarization of the candidates' positions during the pre-election discussion, and the additional criterion is the appeal to the issue of the majority of actors (we will consider the situation in the 2024 presidential elections regarding this a little later). Positions on issues are rated on a scale of -5 to +5, where -5 is strongly negative, +5 is strongly positive, and 0 is centrist or absent.

Once the set of issues has been formed and the positions of the candidates have been evaluated, factor analysis comes into play and pushes the oppositions on isolated issues to major divides, which, following J.Budge and his colleagues in the Manifesto project [3], we refer to as issue dimensions.

The variables are the candidates and the cases are the issues on the political agenda. Traditionally, the factors (political dimensions) worthy of research attention are those whose eigenvalue exceeds one.

For each of the selected factors, variables (candidates) are assigned factor loadings and cases (agenda items) are assigned factor scores. Factor loadings show which candidates oppose each other on each factor: such candidates' factor loadings are most different, ranging from -1 to +1 (usually with opposite sign). The factor scores assigned to the issues on the political agenda allow us to understand which issues polarize party positions on each of the factors the most. The factor scores are highest modulo factor scores for the most pressing issues, with a range of scores beyond -1 and +1.

Within the framework of the Current Political Agenda project, factor analysis is carried out both for the whole set of issues on the political agenda (in this case, the main political dimensions are identified) and for separate issue domains, generally corresponding to those described by Budge et al. The Current Political Agenda project includes four subject areas: 1) domestic policy; 2) socio-economic sphere; 3) foreign policy; 4) worldview issues. However, since the current political agenda of the 2024 presidential campaign included only 36 issues, we had to limit ourselves to dividing this set into only two parts: the first part includes domestic and socio-economic policy issues, while the second part includes foreign policy and worldview issues (with a touch of domestic policy issues).

The contradictions identified by factor analysis in the subject areas are referred to as sub-dimensions. Their factor loadings are used, among other things, to interpret the main political dimensions. Using correlation analysis, the factor loadings of actors in the main political dimensions are compared with their factor loadings in the sub-dimensions. As a rule, the highest modulus correlation coefficients help to ascertain the interpretation of key political dimensions.

The ultimate step is to compare the configuration of presidential candidates' positions in the political and electoral spaces. For this purpose, the factor loadings of candidates in electoral cleavages are compared with their factor loadings in political dimensions and sub-dimensions by means of correlation analysis. If there is a strong correlation with statistical significance less than 0.05, an electoral cleavage is considered to carry a certain political interpretation. There are very few candidates, so all hope is for a low p-level, which indicates that the probability for the correlation relationship to be random is low.

If a specific electoral cleavage carried a political interpretation after the first cut-off, but it disappeared after the second and in the entire set, there is reason for a more thorough, case-by-case analysis.

As for the connection between electoral cleavages and the social framework, we decided not to analyze it this time. As we have already mentioned, the social foundations of cleavages change at a much slower pace than their political markings. Short-term fluctuations in the economic environment by all means can influence voter choice, but only within the framework of already existing political paradigms. Even when a new force bursts onto the political scene, it does so as a result of disillusionment with the previous ideological range, and not of any changes in public interest. Whether this will change the structure of political oppositions and the system of links between conflicts of social interests and new party players will only become clear in the long term.

Moreover, the issue addressed in this study has no direct relation to the social framework.

Political dimensions

Let us begin by analyzing the political space.

Four candidates took part in the election: Vladislav Davankov (New People), Leonid Slutsky (LDPR) and Nikolai Kharitonov (CPRF), as well as self-nominated President Vladimir Putin, who was supported by United Russia along with a number of other parties (A Just Russia — For Truth, Russian Party of Pensioners for Social Justice, Rodina, The Greens Party and others).

During the campaign, candidates generally avoided debating each other. Vladimir Putin has consistently refused to participate in pre-election debates throughout his political career. The other three candidates also preferred not to leave their own campaign "bubbles" and attacked competitors only when they were sure they would beat them. They mostly ignored aggravating topics, focusing the familiar, tried, and tested ones.

As a result, the overwhelming majority of issues on the current political agenda had no more than two "interested parties" (more often only one), while the opinion of the other participants had to be ascertained through indirect evidence: usually from documents or statements of prominent representatives of the nominating or supporting party.

The criteria for including an issue in the current agenda were: 1) polarization of candidates' positions; 2) participation in the discussion of the parties they represented (at the bare minimum). That said, the incumbent was allowed "silent" participation, meaning action or lack thereof was used as a sign of him affirming his position.

The current agenda of the presidential campaign included a total of 36 issues. Sphere-wise these issues break down as follows: 4 in domestic policy, 18 in socio-economic, 2 in foreign policy, 12 in worldview (Matrix sheet of the "2024 Presidential Campaign" summary table [1]).

The marked difference of this agenda from the established inter-party discussion is the unconditionally dominant position of socio-economic issues and the extremely peripheral position of foreign policy issues. In the inter-party discussion, foreign policy is significantly ahead of all other subject areas in terms of representation: out of 127 issues of the current political agenda between December 2023 and February 2024, 49 issues are found in the foreign policy subject area, contrasting with 16 in the domestic policy, 29 in the socio-economic and 33 in the worldview (2024 Presidential Campaign Report [1]).

That is not to say that the candidates avoided discussing foreign policy during the presidential campaign (it was discussed on several occasions), but their positions were not particularly polarized as a rule. And calculations mean nothing without polarization.

Factor analysis of the candidates' positions on 36 issues of the political agenda revealed two main political dimensions (Table 1).

Table 1. Results of factor analysis of candidates' positions on the entire set of issues on the 2024 election campaign

| Variable | Factor Loadings | |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| Vladislav Davankov | 0.545 | 0.711* |

| Vladimir Putin | -0.114 | -0.875* |

| Leonid Slutsky | -0.789* | 0.375 |

| Nikolai Kharitonov | -0.896* | 0.214 |

| Expl.Var | 1.735 | 1.457 |

| Prp.Totl | 43.39% | 36.41% |

* Asterisk marks values >0.7.

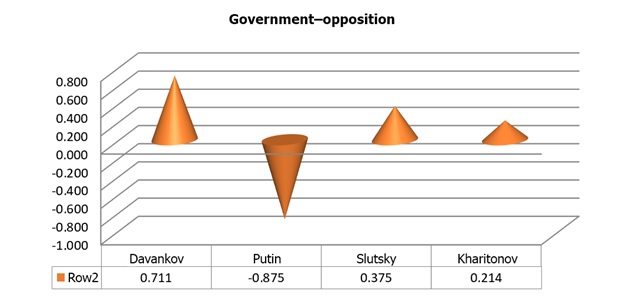

The first of them was an opposition between Nikolai Kharitonov and Leonid Slutsky with Vladislav Davankov (Fig. 1). The issues with the highest modular factor scores were the need for a tough foreign policy course, protection of traditional values, Russia's withdrawal from the Bologna education system, unblocking of social networks, refusal from persecution for dissent and ideological control, and so on. This political dimension was interpreted as "identitarians vs. westernizers". Slutsky and Kharitonov acted as "identitarians", Davankov as a "westernizer".

Figure 1. Opposition within the first political dimension

In the second major political dimension, Vladimir Putin opposed all the other participants, yet Vladislav Davankov above all (Fig. 2). The issue with the highest modulus of factor estimates were primarily socio-economic: redistribution of taxes in favor of regions and municipalities, attitude towards "optimization" of health care and education, indexation of pensions for working pensioners. However, there was also an issue from the domestic policy subject area (popular election of heads of local self-government), as well as from the worldview one with foreign policy connotation — tougher immigration policy. In general, this political dimension is interpreted as "government vs. opposition".

Figure 2. Opposition within the second political dimension

As for the more focused oppositions, distributing 36 issues across four areas made no sense in this case, since only the socio-economic one scored a sufficient number of points (18). Therefore, a different route was taken to form two groups. The first included issues from the domestic policy and socio-economic sphere, the second — from the domestic and foreign policy spheres, as well as worldview (as a result, domestic policy issues were present in both groups).

Factor analysis of candidates' positions on 22 issues of domestic policy and socio-economic subject areas revealed two sub-dimensions (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of factor analysis of candidates' positions on domestic and socio-economic policy issues

| Variable | Factor Loadings | |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| Vladislav Davankov | 0.061 | 0.913* |

| Vladimir Putin | 0.549 | -0.691 |

| Leonid Slutsky | -0.929* | -0.110 |

| Nikolai Kharitonov | -0.935* | -0.237 |

| Expl.Var | 2.042 | 1.379 |

| Prp.Totl | 51.05% | 34.48% |

* Asterisk marks values >0.7.

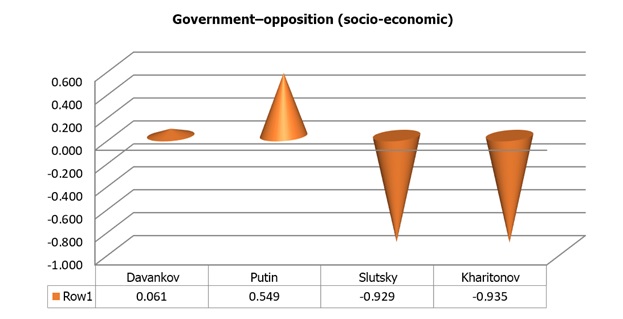

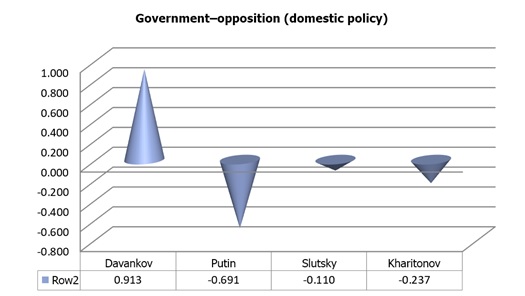

The opposition between Vladimir Putin, on the one hand, and Leonid Slutsky and Nikolai Kharitonov, on the other, was in the lead (Fig. 3). The greatest polarization was identified on socio-economic issues: reduction (elimination) of VAT, changing retirement age back to its previous numbers, administrative restriction of prices and tariffs, reduction of the maximum allowable share of citizens' expenditures on housing and utilities services, return of money to 1990s depositors, abolition (freezing, reduction) of contributions to the capital repair of apartment buildings, abolition of the transport tax. This sub-dimension may well be interpreted as an opposition between the government and the opposition in the socio-economic sphere.

Figure 3. Opposition between the government and the opposition on socio-economic issues

In the second sub-dimension, Vladimir Putin and Vladislav Davankov opposed each other (Fig. 4). In this case, polarization went beyond socio-economic issues, occurring in domestic policy issues as well: unbanning social networks, stopping ideological control and persecution for dissent, criticising the use of administrative resource in elections, popular election of heads of local self-government. In this regard, this sub-dimension was interpreted as an opposition between the government and the opposition in the domestic policy sphere.

Figure 4. Opposition between the government and the opposition on domestic political issues

Factor analysis of the candidates' positions on 18 issues of domestic and foreign policy, as well as worldviews domain revealed only one sub-dimension: Vladislav Davankov in opposition to all other election participants (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of factor analysis of candidates' positions on issues of domestic, foreign policy and worldview subject areas

| Variable | Factor 1 |

| Vladislav Davankov | 0.875* |

| Vladimir Putin | -0.759* |

| Leonid Slutsky | -0.691 |

| Nikolai Kharitonov | -0.754* |

| Expl.Var | 2.388 |

| Prp.Totl | 59.70% |

* Asterisk marks values >0.7.

The polarization was most pronounced on such issues as tighter "foreign agents" legislation, protecting traditional values, unbanning social networks, and stopping ideological control and persecution for dissent. The sub-dimension can be interpreted as "westernizers vs. identitarians," but to avoid confusing it with the first major political dimension, let us call it "hawks–doves."

The correlation analysis of the connection of the candidates' positions in the main political dimensions with their positions in the sub-dimensions did not yield convincing results this time (Table 4). Both major political dimensions had strong correlations with all sub-dimensions, but these correlations were statistically unreliable: nowhere was the p-level less than not only 0.05, but also 0.1.

Table 4. Correlation analysis of links between key political dimensions and sub-dimensions in subject areas

| Variable | Correlations | |

| Political Dimension – 1 | Political Dimension – 2 | |

| Socioeconomic: government–opposition | 0.772 p=0.229 | -0.559 p=0.441 |

| Domestic policy: government–opposition | 0.616 p=0.384 | 0.843 p=0.157 |

| "Hawks"–"doves" | 0.846 p=0.154 | 0.608 p=0.393 |

The first main political dimension correlated most strongly with the "hawks-doves" sub-dimension, the second — with the opposition between the government and the opposition in the internal political sphere. However, the results were devalued by the high probability of the random nature of the linkage, which is not surprising given the curtailed political agenda.

Relation of political (sub)dimensions to electoral cleavages at the level of constituent entities and territorial election commissions

Analysis of the normal distribution of turnout in 90 federal subjects (including the newly admitted ones) and territories outside the Russian Federation produced quite an irregular picture of not just occasional "humps", but of an entire "mountain range". The first cut-off was done at a turnout level of 73% (28 federal subjects), while the second cut-off was done at 89% (78).

The factor analysis of the share of votes received by candidates in all federal subjects revealed two electoral cleavages (Table 5).

Table 5. Results of factor analysis of vote returns for candidates in 90 constituent entities of the Russian Federation and territories outside the Russian Federation

| Variable | Factor Loadings | |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| Invalid | 0.835* | -0.501 |

| Vladislav Davankov | 0.885* | -0.428 |

| Vladimir Putin | -0.999* | -0.022 |

| Leonid Slutsky | 0.714* | 0.514 |

| Nikolai Kharitonov | 0.588 | 0.694 |

| Expl.Var | 3.332 | 1.181 |

| Prp.Totl | 66.65% | 23.61% |

* Asterisk marks values >0.7.

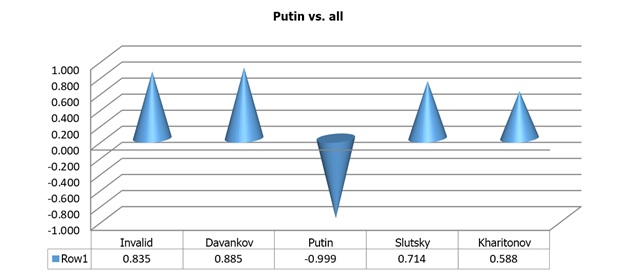

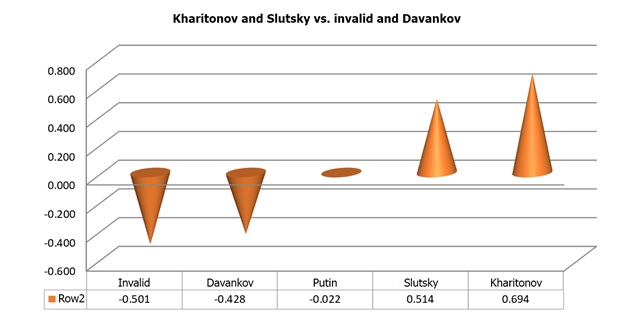

The first of the ECs represented the opposition between Vladimir Putin, on the one hand, and all other candidates and the shares of invalid ballots, on the other (Fig. 5), the second — the opposition between Nikolai Kharitonov and Leonid Slutsky and Vladislav Davankov and the shares of invalid ballots (Fig. 6).

Figure 5. First electoral cleavage in 90 federal constituent entities and territories outside the Russian Federation

Figure 6. Second electoral cleavage by 90 federal constituent entities and territories outside the Russian Federation

The factor analysis of vote returns within the first cut-off (28 federal subjects) also revealed two electoral cleavages (Table 6). If we think beyond from the change of signs of factor loadings (they do not matter in this case), then here are practically the same oppositions, though with slight nuances. In the first electoral cleavage, the factor loadings of Davankov, Kharitonov and invalid ballots are lower in modulus, but the factor loadings of Slutsky are higher. In the second one, the factor loadings of Kharitonov and Davankov are higher, but the factor loadings of Slutsky and invalid ballots are lower.

Table 6. Results of factor analysis of vote returns in 28 constituent entities of the Russian Federation

| Variable | Factor Loadings | |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| Invalid | -0.656 | 0.437 |

| Vladislav Davankov | -0.780* | 0.471 |

| Vladimir Putin | 0.995* | 0.055 |

| Leonid Slutsky | -0.900* | -0.218 |

| Nikolai Kharitonov | -0.485 | -0.831* |

| Expl.Var | 3.073 | 1.154 |

| Prp.Totl | 61.46% | 23.09% |

* Asterisk marks values >0.7.

The factor analysis within the second cut-off (78 federal subjects) left only one electoral cleavage, which configuration-wise was close to the first EC within the analysis of the whole set of regions (Table 7).

Table 7. Results of factor analysis of vote returns in 78 constituent entities of the Russian Federation

| Variable | Factor 1 |

| Invalid | 0.840* |

| Davankov | 0.874* |

| Putin | -0.997* |

| Slutsky | 0.738* |

| Kharitonov | 0.578 |

| Expl.Var | 3.340 |

| Prp.Totl | 66.80% |

* Asterisk marks values >0.7.

The correlation analysis of factor loadings in electoral and political spaces revealed the strongest correlation of the first electoral cleavage with the second main political dimension ("government–opposition") in all three variants of factor analysis (Table 8).

Table 8. Correlation analysis of links between factor loadings in the electoral and political spaces at the level of constituent entities of the Russian Federation

| Variable | EC100-1 | EC100-2 | EC89-1 | EC73-1 | EC74-2 |

| Political Dimension – 1 | -0.069 p=0.931 | -0.994* p=0.006 | -0.078 p=0.922 | 0.136 p=0.864 | 0.915 p=0.085 |

| Political Dimension – 2 | 0.986* p=0.014 | -0.023 p=0.977 | 0.985* p=0.015 | -0.966* p=0.034 | 0.073 p=0.927 |

| Socioeconomic: government–opposition | -0.688 p=0.312 | -0.814 p=0.186 | -0.694 p=0.306 | 0.730 p=0.270 | 0.720 p=0.280 |

| Domestic policy: government–opposition | 0.743 p=0.257 | -0.551 p=0.449 | 0.737 p=0.263 | -0.687 p=0.313 | 0.538 p=0.462 |

| "Hawks"–"doves" | 0.470 p=0.530 | -0.796 p=0.204 | 0.462 p=0.539 | -0.396 p=0.604 | 0.738 p=0.262 |

* Asterisk marks values with p<0.05.

As for the second electoral cleavage, it had a significant correlation with the first main political dimension ("westernizers–identitarians"), but only for the entire set of regions and territories outside the Russian Federation. For the regions within the first cut-off (28 federal subjects), the link between the second EC and the first PD had too high a p-level — above 0.05, although under 0.01. This is a sign that a significant contribution to this link was made by votes cast outside the Russian Federation, where Davankov received 16.65%.

Whatever the case, what we can observe here is a turning point of sorts. For the first time in over 20 years, the second electoral cleavage is linked not with the conservative, but rather with the liberal (albeit very moderate) opposition.

The normal distribution of turnout in 3201 territorial commissions also resembled a mountain range with a sharp rise at the very end: turnout amounted to 100% in 203 TECs and to over 99% in 71. However, the second cut-off point was assigned to 93% (2504 TECs) and the first cutoff to 49% (140). Factor analysis in all three sets revealed two factors for each (Table 9).

Table 9. Results of factor analysis of vote returns in 3201, 2504 and 140 territorial election commissions

| Cut-off point | 100% | 93% | 49% | |||

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Invalid | 0.941* | -0.186 | 0.875* | -0.381 | -0.834* | 0.477 |

| Davankov | 0.963* | -0.171 | 0.892* | -0.385 | -0.926* | 0.305 |

| Putin | -0.989* | -0.128 | -0.996* | -0.060 | 0.988* | -0.141 |

| Slutsky | 0.147 | 0.851* | 0.442 | 0.689 | -0.528 | -0.774* |

| Kharitonov | 0.102 | 0.862* | 0.447 | 0.697 | -0.719* | -0.572 |

| Expl.Var | 2.824 | 1.547 | 2.949 | 1.257 | 3.325 | 1.265 |

| Prp.Totl | 56.49% | 30.95% | 58.98% | 25.15% | 66.50% | 25.31% |

* Asterisk marks values >0.7.

The correlation analysis of the links between the factor loadings of the candidates in the electoral space and their loadings in the political space (Table 10) has revealed that the first electoral cleavage in all the sets had a strong significant correlation with the second political dimension ("government–opposition"), while the second EC at the stages of the first and second cut-off correlated with the first PD ("westernizers–identitarians"), and for the sum-totals of TECs — with the opposition between the government and the opposition in socio-economic issues. It turns out that it was in the 700 territorial election commissions with the highest turnout that dispersion for Kharitonov and Slutsky increased, while dispersion for Davankov and invalid ballots decreased.

Table 10. Correlation analysis of links between factor loadings in electoral and political spaces at the level of territorial election commissions

| Variable | EC100-1 | EC100-2 | EC93-1 | EC93-2 | EC49-1 | EC49-2 |

| Political Dimension – 1 | 0.311 p=0.689 | -0.925 p=0.075 | 0.059 p=0.941 | -0.984* p=0.016 | 0.041 p=0.959 | 0.972* p=0.029 |

| Political Dimension – 2 | 0.972* p=0.028 | 0.288 p=0.712 | 0.995* p=0.005 | 0.078 p=0.923 | -0.975* p=0.025 | 0.054 p=0.946 |

| Socioeconomic: government–opposition | -0.363 p=0.637 | -0.955* p=0.045 | -0.588 p=0.412 | -0.869 p=0.131 | 0.659 p=0.341 | 0.773 p=0.227 |

| Domestic policy: government–opposition | 0.940 p=0.060 | -0.272 p=0.728 | 0.822 p=0.178 | -0.471 p=0.529 | -0.755 p=0.245 | 0.575 p=0.425 |

| "Hawks"–"doves" | 0.769 p=0.231 | -0.584 p=0.416 | 0.581 p=0.419 | -0.744 p=0.256 | -0.497 p=0.503 | 0.818 p=0.183 |

* Asterisk marks values with p<0.05.

This cannot help but raise questions. The logic of ensuring maximum votes to the incumbent implies the growth of Vladimir Putin's result, and if candidates from the conservative left opposition happen to win (at least in some territorial commissions), it looks strange. Of course, we can assume that it was the high results of Slutsky and Kharitonov that activated the desire to maximize the number of votes in favor of Putin, but then why did the same thing not happen in the TECs that had a high percentage of votes for Davankov? After all, the situation was supposedly even more dangerous there.

To clarify these oddities, let us consider the election results at the level of precinct election commissions.

Relation of political (sub)dimensions to electoral cleavages at the level of precinct election commissions (by regions)

Before analyzing the relationship between political (sub)dimensions and electoral cleavages at the PEC level, let us examine the voting situation in the regions from the point of view of such parameters as total turnout, PECs with minimum turnout, the share of precinct election commissions with turnout over 90%, the number of electoral cleavages at different cut-off levels: the first, the second, the entire set (Table 11).

The data in this table are sorted by total turnout. As a reminder, it does not include the newly admitted territories from which no PEC data have been received.

Table 11. Voting in the regions by precinct election commissions in terms of turnout and number of electoral cleavages

| Region | Turnout | Number of ECs | ||||

| General | PECs with minimal turnout | Share of PECs with turnout >90% | 1st cut-off | 2nd cut-off | 100% | |

| Komi Republic | 58.51 | 32.50 | 5.16 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Altai Krai | 59.81 | 24.24 | 5.41 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Karelia | 59.88 | 34.33 | 1.08 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Tomsk Oblast | 60.04 | 31.35 | 0.67 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Udmurtia | 62.53 | 32.92 | 8.72 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Novosibirsk Oblast | 63.11 | 28.95 | 10.54 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Irkutsk Oblast | 63.15 | 16.67 | 9.39 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Khabarovsk Krai | 64.67 | 34.43 | 19.80 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Arkhangelsk Oblast | 65.01 | 20.00 | 10.69 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Zabaykalsky Krai | 65.33 | 38.59 | 6.85 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Novgorod Oblast | 66.40 | 27.28 | 1.73 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Moscow | 66.41 | 14.83 | 5.91 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Kirov Oblast | 66.48 | 45.09 | 9.58 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Kaluga Oblast | 68.00 | 36.23 | 22.05 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Pskov Oblast | 68.20 | 37.42 | 7.68 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Mari El | 68.89 | 42.94 | 9.51 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Vladimir Oblast | 69.01 | 30.75 | 9.71 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Kostroma Oblast | 69.15 | 45.13 | 9.00 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

The table is not fully displayed Show table

This picture is quite familiar to that of the previous election: among the regions with the lowest turnout are the Komi Republic, Altai Krai, Karelia, Tomsk Oblast, and Udmurtia (although even there the turnout did not go below 58.5%), among the regions with the highest turnout are the North Caucasus republics, Kuzbass, and territories outside the Russian Federation (the latter because of the particular way electoral rolls are generated).

According to the "PECs with minimal turnout" parameter, Moscow, Irkutsk Oblast, Primorsky Krai, and Arkhangelsk Oblast fell to one flank, and the very same national republics — Chechnya, Karachay-Cherkessia, Kabardino-Balkaria and Tyva — to the other.

A similar picture emerged with precinct election commissions with a turnout of over 90%. On one pole are Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Tomsk Oblast, Karelia, Novgorod Oblast; on the other pole are yet again Chechnya, territories outside Russia, Kemerovo Oblast, Kabardino-Balkaria, Tyva.

As for the number of electoral cleavages at different cut-off levels, we were interested in the regions where the number of ECs increased rather than decreased with the increase in the cut-off level. One would think that the opposite makes more sense: the higher the turnout, the higher the vote for the incumbent, which usually neutralizes all other cleavages. If, on the contrary, the number of ECs is increasing, this is cause for alarm.

This eliminates instantly the cases of Chechnya, Kuzbass and territories outside the Russian Federation, where the normal distribution of turnout was "one-humped" (due to very high turnout at all polling stations), as well as Karachay-Cherkessia and Chukotka with their "two-humped" normal distribution, since only one cut-off can be made. Kabardino-Balkaria also indicated two "humps", yet in this case the factor analysis of the whole set of PECs revealed still more electoral cleavages than the analysis of the cut-off set.

Other attention-worthy cases included Kamchatka, as well as Vologda and Oryol Oblasts, where the entire set of PECs revealed more electoral cleavages than the set after the second cut-off; other such cases included the Altai Republic, Perm Krai, Bryansk, Kursk and Tyumen Oblasts, where the number of ECs after the second cut-off was higher than after the first one. Logic suggests that the opposite is true: the lower the turnout, the more variations there are. We will come back to these regions in case we encounter anything strange in the political interpretation of electoral cleavages (or lack of said interpretation).

Unfortunately, it was not possible to construct a summary table of correlations between electoral cleavages in the regions and political (sub)dimensions — it would have been too cumbersome and would not have added to clarity. Therefore, we will limit ourselves to a general description, referring to tables only in individual cases.

The most common variation was the recurrence at all three levels (first cut-off, second cut-off, entire set) of a configuration where the first EC significantly correlated with the second major political dimension ("government–opposition").

There are 32 such regions in total: Arkhangelsk, Vladimir, Voronezh, Jewish Autonomous, Ivanovo, Kaliningrad, Kurgan, Leningrad, Lipetsk, Murmansk, Omsk, Orenburg, Penza, Rostov, Ryazan, Tula, Ulyanovsk Oblasts, Zabaikalsky, Krasnoyarsk and Primorsky Krais, Altai Republic, Bashkortostan, Buryatia, Karelia, Tyva, Khakassia, Udmurtia, Chuvashia, Moscow and Sevastopol.

In most cases, at different cut-off levels, second and sometimes third cleavages were revealed there, yet without political interpretation, and also because often these extra ECs resulted from a high spread of invalid ballots.

One can say that if ballot stuffing did take place in these regions, it was done only in favor of the incumbent, and did not shift the balance of power by and large. Putin's victory was secured more by lack of choice than by ballot stuffing. From the list of "suspicious" regions, only the Altai Republic was in this group: the appearance of the second EC in the second cut-off and the full set of PECs was most likely explained by the fact that as the turnout increased, so did the average value of the share of those who voted not only for Vladimir Putin, but also for Nikolai Kharitonov, which does not look unusual for this federal subject.

The second most common configuration is when, along with the first EC closely correlated with the second main political dimension, there was also a second EC associated with the first main PD ("westernizers–identitarians") at different cut-off levels. There were 17 such regions: Altai and Krasnodar Krais; Komi and Mordovia Republics; Bryansk, Vologda, Irkutsk, Kirov, Kursk, Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Pskov, Samara, Smolensk, Tver, Chelyabinsk and Yaroslavl Oblasts.

The "suspicious" regions in this group included Bryansk, Vologda and Kursk Oblast.

In Bryansk Oblast, the emergence of an additional, third, electoral Bryansk Oblast after the second cut-off coincides with an increase in the average share of votes for Slutsky: in a number of PECs (mainly in Bryansk) the number of votes for him exceeded 10%. At the same time, the average value of voting for Putin consistently increased along with the turnout, while the average value of voting for Davankov and Kharitonov decreased in the same consistent manner. One cannot rule out isolated instances of ballot stuffing for Slutsky in this region.

The third EC emerging as the turnout approached 100% in Vologda Oblast can also be associated with the growth of the average value of the share of those who voted for Slutsky. Incidentally, this third EC had no political interpretation, and its very emergence is explained precisely by the dispersion in voting for Slutsky (in some PECs the number of votes received by him went over 10%: up to 16.67% in one of the polling stations in Vologda).

The increase in the average value of the share of those who voted for Slutsky can be associated with the second EC emerging within the second cut-off in Kursk Oblast: for the other candidates, this value either consistently increased (Putin) or consistently decreased (Davankov and Kharitonov). That said, in all three regions, one cannot rule out isolated instances of ballot stuffing for Slutsky. Naturally, we cannot say this with complete certainty; we need to determine specifically where Slutsky's share of the vote increased unexpectedly. If it happened, for example, at a detention facility, nothing is out of the ordinary.

In seven regions (Amur, Kaluga, Kostroma, Novosibirsk, Tomsk Oblasts, Perm Krai and Kalmykia), at different cut-off levels, the first EC with power–opposition marking (the second political dimension) was accompanied by the second EC that with the socio-economic sub-dimension. In Novosibirsk Oblast, it had a conservative left marking in the first cut-off, yet it was lost in the second. In the full set of PECs it had already established a connection with the first political dimension ("westernizers–identitarians"). In other words, Novosibirsk Oblast belonged to both the second and third groups of regions.

Perm Krai was the "suspicious" region included in this group. Here we could also observe an increase in the average value of the share of those who voted for Slutsky in the second cut-off. However, this time Slutsky was accompanied by Kharitonov, and this actually explains the socio-economic marking of the second EC quite well–LDPR and CPRF candidates collectively opposed Putin in it. And it was the voting for Slutsky that had the strongest factor loading in this EC. As a consequence, one cannot rule out ballot stuffing for Slutsky in this case either.

Another five regions — Kabardino-Balkaria, Ingushetia, Chechnya, St. Petersburg and the Nenets Autonomous Okrug — stood out because none of the electoral cleavages identified there had a political interpretation. While this is a common occurrence in the North Caucasus republics, seeing St. Petersburg and the Nenets Autonomous Okrug in this company raises eyebrows. Before 2021, St. Petersburg never failed to indicate several electoral cleavages with a clearly expressed political interpretation, but in recent years, it has been rapidly losing this feature [11]. By 2024, it appears to have lost it completely.

And the reason for this was a sharp increase in the spread in voting for Slutsky, especially as turnout increased. As it approached 100%, the swing in this vote ranged from 0 to 27.27%.

The fact is that there were no political (sub)dimensions where Slutsky became a pole in an opposition, while Davankov and Putin did so in four out of five cases, and Kharitonov in two. Therefore, the increase in the spread in voting for Slutsky could not reinforce the correlation between electoral cleavages and political (sub)dimensions, but it could very well knock it down or increase its p-level.

It should also be noted that in St. Petersburg the second EC at all cut-off levels was the result of a high variation in voting for Slutsky (Table 12). So the assumption about ballot stuffing in favor of Slutsky looks quite plausible.

Table 12. Electoral cleavages in the 2024 presidential election in St. Petersburg in the entire set, in 86% and 59% of PECs

| Cut-off point | 100% | 86% | 59% | |||

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Invalid | 0.667 | 0.219 | -0.713* | -0.390 | 0.826* | -0.253 |

| Davankov | 0.865* | -0.294 | -0.899* | 0.182 | 0.902* | 0.333 |

| Putin | -0.912* | -0.362 | 0.862* | 0.434 | -0.926* | 0.305 |

| Slutsky | -0.204 | 0.962* | 0.435 | -0.845* | -0.284 | -0.862* |

| Kharitonov | 0.459 | -0.057 | -0.456 | 0.263 | 0.126 | -0.433 |

| Expl.Var | 2.277 | 1.195 | 2.456 | 1.156 | 2.450 | 1.198 |

| Prp.Totl | 45.54% | 23.90% | 49.13% | 23.13% | 48.99% | 23.96% |

* Asterisk marks values >0.7.

A similar case could be observed in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug. Abnormally high results of voting for the LDPR leader (up to 21.43%) were recorded there only at a few polling stations, but, at the same time, NAO only has 54 PECs. This was enough to deprive the main electoral cleavage — Putin vs. the opposition — of political interpretation (Slutsky, by the way, found himself not among the opposition, but in the center, and closer to the incumbent).

In other regions, the variants of correlation of electoral cleavages with political (sub)dimensions were very different. On the other hand, the unifying fact was that the first EC either had no political interpretation or had it only at one cut-off level (sometimes two). In general, these regions are divided into three groups depending on which political (sub)dimension was associated with the second EC (and sometimes with the first): 1) one of the ones forming around Davankov (EC-1, "hawks-doves", domestic political): Astrakhan, Belgorod, Volgograd, Nizhny Novgorod and Sakhalin Oblasts, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Crimea; 2) socio-economic: Oryol and Tyumen Oblasts, North Ossetia, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug; 3) both: Karachay-Cherkessia (the first EC was socio-economic; the second correlated simultaneously with both domestic political and "hawks-doves"), Tatarstan, Stavropol Krai (the first was socio-economic, the second was "hawks-doves").

The second group includes Oryol Oblast, which was earlier included in the list of "suspicious" regions due to the number of electoral cleavages increasing along with the turnout. In this case, however, the suspicions of ballot stuffing for Slutsky are likely unfounded. The third EC in the analysis of the whole set of polling stations was formed as a result of an increase in the spread of the share of invalid ballots.

In one more of the "suspicious" regions, Kamchatka Krai, where the first EC within the first cut-off had a significant correlation with the second main PD, the loss of this connection as the turnout grew is indeed linked to Slutsky's votes being scattered. However, one should take into account that the increase in this scattering was mostly found among the ship crews, and these voters never went along with the all-Russian trends.

Finally, the last of the "suspicious" regions, Tyumen Oblast, is characterized by a "red" voting pattern: at the first and second cut-offs, the first EC significantly correlated with the socio-economic sub-dimension, i.e. Slutsky and Kharitonov opposed Putin. The second EC at the first cut-off (75%) did not emerge at all. At the second cut-off (90%), it correlated with the second main PD (quite a non-standard case, but one should keep in mind that Putin opposed Davankov in this case). For the whole set of PECs, it correlated with the "hawks–doves" sub-dimension. The first EC in the analysis of the entire set of polling stations had a high correlation coefficient with the socio-economic dimension (0.941), but this relationship was compromised by a p-level exceeding 0.05, and there is every reason to believe that this increase in the p-level is due to the strong variation in voting for Slutsky as turnout approached 100% (over 20% in some polling stations). That said, one cannot rule out ballot stuffing for Slutsky.

Conclusion

Despite the general abnormality of the 2024 presidential election, it is worth recognizing that, on the whole, it followed an understandable political logic and is not the result of pure fraud. Indeed, Vladimir Putin's result was ensured by purposeful work of the entire state apparatus. Still, to a greater extent, this result was ensured by voters having been given a limited choice and by the most favourable and unfavourable conditions having been created, respectively, for the incumbent and his "competitors" (or junior partners, to be more precise).

The main effort was directed at getting voters to vote by any means necessary. Of course, ballot stuffing for the incumbent did take place, if only because of the decades-long tradition, but it did not shift the overall balance of power.

A more interesting question is whether there was ballot stuffing for Slutsky. Judging by the results of this study, there was: in St. Petersburg and Nenets AO specifically; possibly in Bryansk, Vologda, Kursk and Tyumen Oblasts. Yet these instances of ballot stuffing were mostly isolated and did not have much impact. If there was indeed an objective to push the LDPR leader to the second place, it was not met.

Moreover, the nature of the correlation between electoral cleavages and political (sub)dimensions clearly indicates a disruption in previous trends, where the incumbent's main political rival came from the opposition on the conservative left [9]. It was this opposition that had previously imbued the first electoral cleavage.

The 2024 presidential election was the first time when the incumbent was opposed not so much by a social conservative candidate, but by a liberal and a "dove" (albeit a very moderate one). On the poles of the second main political dimension, which mainly shaped the first electoral cleavage, Putin was opposed not by Kharitonov or Slutsky, but by Davankov. The socio-economic sub-dimension, within which Kharitonov and Slutsky opposed the incumbent, imbued the first EC only in nine cases and the second EC in six. All other cases represented an opposition between Putin and Davankov.

Received 08.10.2024, revision received 16.10.2024.

References

- Aktualnaya politicheskaya povestka Rossii v mezhpartiinoi diskussii [Russia's Current Political Agenda in Inter-Party Discussion]. - Website of INION of RAS. URL: https://inion.ru/ru/science/nauchnye-proekty/aktual-naia-politicheskaia-povestka/ (accessed 13.11.2024). (In Russ.) - https://inion.ru/ru/science/nauchnye-proekty/aktual-naia-politicheskaia-povestka/

- Budge I., Homola J. How Far Have European Political Parties Followed the Americans to the Right in the Later Post-War Period? – Cambio. Rivista sulle Trasformazioni Sociali. 2012. Vol. 2. Iss. 4. P. 71–86.

- Budge I. The internal analysis of election programmes. – Ideology, Strategy and Party Change: Spatial Analyses of Post-War Election Programmes in 19 Democracies, Budge I., Robertson D., Hearl D. (eds.). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987. P. 15–38.

- Deegan-Krause K. New Dimensions of Political Cleavage. – Oxford Handbook of Political Science / ed. by R.J. Dalton, H.-D. Klingemann. Oxford-New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. P. 538–556. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199270125.003.0028.

- Golosov G.V. Politicheskiye rezhimy i transformatsii: Rossiya v sravnitelnoi perspektive [Political Regimes and Transformations: Russia in Comparative Perspective]. Moscow: Ruthenia, 2024. (In Russ.)

- Janda K. A Tale of Two Parties: Living amongst Democrats and Republicans since 1952. New York and London: Routledge, Tailor and Francis Group, 2021.

- Korgunyuk Yu.G. Electoral Cleavage Structure: 2021 State Duma Election. – Electoral Politics. 2023. No. 1 (9). P. 1. - http://electoralpolitics.org/en/articles/struktura-elektoralnykh-razmezhevanii-po-itogam-dumskikh-vyborov-2021-goda/

- Korgunyuk Yu.G. Kontseptsiya razmezhevaniy i teoriya problemnykh izmereniy: tochki peresecheniya [Intersections of Cleavages Concept and Issue Dimensions Theory]. – Polis. 2019. No. 6. P. 95–112. DOI: 10.17976/jpps/2019.06.08 (In Russ.)

- Korgunyuk Yu.G. Prezidentskiye vybory v postsovetskoi Rossii cherez prizmu konteptsii razmezhevaniy [Presidential Elections in Post-Soviet Russia Through the Lens of the Cleavage Concept]. – Politeia. 2018. No. 4. P. 32-69. DOI: 10.30570/2078-5089-2018-91-4-32-69 (In Russ.)

- Korgunyuk Yu. Issue Dimensions and Cleavages: How the Russian Experience Helps to Look for Cross-points. – Russian Politics. 2020. Vol. 5. Iss. 2. P. 206–235. DOI: 10.30965/24518921-00502004.

- Korgunyuk Yu. Russia's Regional Parliament Elections (2021): Cleavage Structure and Trends of Changes. – Russian Politics. 2024. Vol. 9. Iss. 2. P. 197–235. DOI: 10.30965/24518921-00902002.

- Lipset S.M., Rokkan S. Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction. – Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York; London: The Free Press, Collier-MacMillan limited. 1967. P. 1–64.

- Lukyanova Ye., Poroshin Ye. (ed.) Vybory strogogo rezhima. Kak rossiiskiye vybory stali nevyborami i cho s etim delat? Politiko-pravovoye issledovaniye s elementami matematiki. [Maximum Security Elections: How Did Elections in Russia Turn Into Non-Elections and What is to Be Done About It? A Political and Legal Research With Elements of Mathematics]. Moscow: Mysl, 2022. (In Russ.)

- Moreno A. Political Cleavages: Issues, Parties and the Consolidation of Democracy. Boulder: Westview Press, 1999.

- Rae D.W., Taylor M. The Analysis of Political Cleavages. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1970.

- Shpilkin S., Arutyunov A. Matematicheskiye metody fiksatsii sposobov dostizheniya tselei i zadach avtoritarnoi vlasti [Mathematical Methods of Tracing the Ways Authoritarian Governments Achieve Their Goals and Objectives]. – Vybory strogogo rezhima. Kak rossiiskiye vybory stali nevyborami i cho s etim delat? Politiko-pravovoye issledovaniye s elementami matematiki [Maximum Security Elections: How Did Elections in Russia Turn Into Non-Elections and What is to Be Done About It? A Political and Legal Research With Elements of Mathematics] / edited by Ye. Lukyanova and Ye. Poroshin. Moscow: Mysl, 2022. P. 341–364. (In Russ.)

- Whitefield S. Political Cleavages and Post-Communist Politics. – Annual Review of Political Science. 2002. Vol. 5. P. 181–200.

- Zuckerman A. Political Cleavage: A Conceptual and Theoretical Analysis. – British Journal of Political Science. 1975. Vol. 5. P. 231–248.