"Green islands" in the "sea of red": on the assessment of the official results of the 2024 presidential election in Perm Krai and the effectiveness of the policy to achieve them

Abstract

The paper considers the official results of the 2024 Russian presidential election in Perm Krai. The analysis revealed significant discrepancies in the results between polling stations that were equipped with ballot paper processing systems (KOIB) and the regular polling stations. KOIB-equipped PECs were found to record significantly lower voter turnout, less support for Vladimir Putin and more support for Vladislav Davankov than those where votes were counted manually. The author also considered how KOIBs were used in previous elections held in the region and whether anything in their use changed in the presidential election. Among other issues examined are results of a comparative cross-territorial and cross-system analysis of vote returns in the territories with automated and manual vote counting. The author concludes that the identified discrepancies diverge from the regular practice and have an artificial character due to anomalous results at the polling stations where votes are counted manually. The work is summarized in a model of distortion-free vote returns in Perm Krai, which was created using the data from polling stations with PECs.

Introduction: paradoxes of electoral geography and official indicators of the 2024 Russian presidential election in Perm Krai

The Perm Krai Election Commission (PKEC) confirmed the following results of the March 2024 presidential election in the region [Vybory Prezidenta Rossiyskoi]: Vladimir Putin won a landslide victory with 84.65%, while the other candidates received approximately equal amounts and shares of the vote: 4.96% went to Nikolai Kharitonov (CPRF), 4.79% to Leonid Slutsky (LDPR), 4.53% to Vladislav Davankov (New People). Voter turnout was 80.91%. Regional figures were not that different from the all-Russian results approved by the CEC of Russia: 87.28% for Putin, 4.31% for Kharitonov, 3.85% for Davankov, 3.20% for Slutsky [12].

The official results in the region turned out to be very close to the numbers projected on the eve of the vote by state sociological services (for example, VTsIOM projected a turnout of 71% and the victory of Vladimir Putin with a result of 82%, leaving the other candidates with 5-6%) [17], as well as to the statements made by various government representatives. For example, Evgeny Shevchenko, a member of the CEC of Russia, who visited Perm Krai on the eve of the election, predicted a turnout of 82-85% [16].

The indicators of the candidate of the symbolic "party of power" and voter turnout in national elections are considered to be signs of the stability of a regime like the Russian one, its ability to ensure the political mobilization of the masses in its own interests [3: 70]. They also serve as a form of demonstrating the manageability and loyalty of the regions, so managing them is the direct responsibility of regional governments. This is where a regional government puts its special efforts, often having to ensure its own survival in this manner. Ensuring certain electoral results (election results management) is the most important direction of domestic regional policy. Regional governments are implementing various strategies and tools to achieve these results.

Although they have quite a diverse "menu of manipulations" to ensure the desired outcome of elections [13], Perm Krai has never been engaged in large-scale vote return fraud before. From the point of view of the observer community, Perm Krai was one of the so-called "green" regions. Election results were managed by administrative and mobilization methods. Over many years of electoral observation, only two episodes that showed distortion of the results of the expression of the will of the voters in some districts of Perm Krai have been documented, and both occurred after the appointment of Dmitry Makhonin as governor in February 2020. In the summer of 2020, during the all-Russian voting, the vote returns "in favor" of constitutional amendments were nearly identical 38 commissions of Perm's Ordzhonikidzevsky District with 71.9% [6]. Moreover, there was evidence of shady manipulation of electoral, among other distortions [5]. In September of the same year, video surveillance in Perm Krai gubernatorial election revealed that the results of vote counting at seven polling stations of Perm's Sverdlovsky District significantly differed from the data filed to the SAS "Vybory" [7].

In this regard, the case of Perm Krai in 2024 is of interest as an example of how regional electoral policy is transformed and where it is headed at the new stage of development of the Russian political regime.

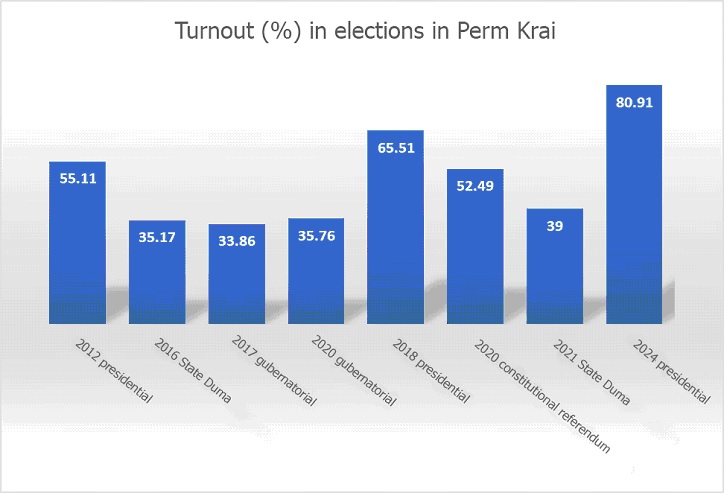

Voters in Perm Krai have never shown any special support for the government-endorsed candidates or been active even at the presidential election (Fig. 1). As a result, regional government had quite a challenging task set before them in 2024. Nevertheless, the task was solved by indicating a sharp increase in official voter turnout of almost +15 points compared to 2018. The indicators of support for Vladimir Putin also increased.

Figure 1. Turnout at federal and regional elections in Perm Krai

However, even a cursory glance at the official results reveals some marked discrepancies.

Perm Krai was one of the regions where remote electronic voting (REV) was used. Over 183 thousand or 9.3% of voters in the region chose to cast an e-vote. While the results of both electronic and paper voting were almost identical for two candidates — Putin (84.64% by paper voting and 84.75% by e-voting) and Slutsky (4.80% and 4.71% respectively), the results of the other two candidates, Davankov and Kharitonov, were markedly different depending on the method of voting. REV data indicate that Davankov came in second place in Perm Krai with 8.15% of the electronic vote, but in the paper ballot he came in a final fourth place with only 4.06% of the popular vote. Kharitonov, on the other hand, received the least votes through REV: only 2.38% with 5.30% and second place through the paper ballot. What explains the differences in the results of electronic and paper voting for two of the four candidates? It seems that the answer here lies in the nature of the data relative to traditional paper ballot voting.

It should be noted that all the following calculations and figures refer only to paper ballot voting in Perm Krai.

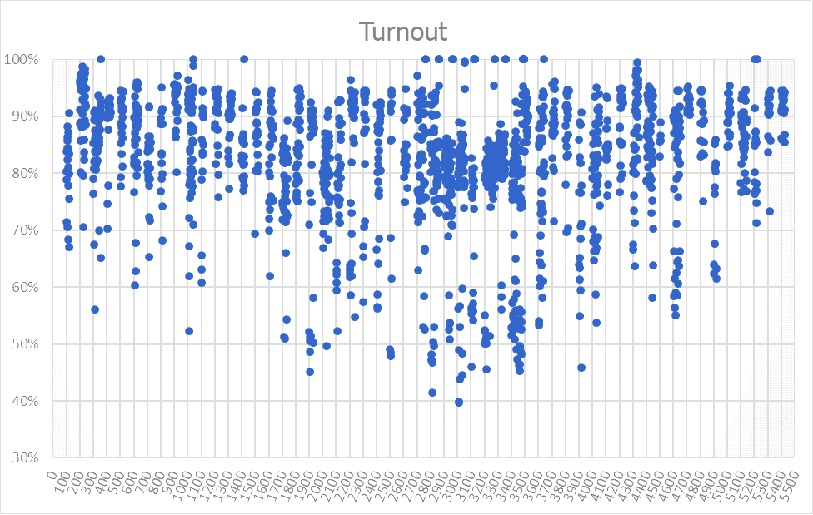

Looking at the official results of voter turnout by polling station in terms of TECs (Figure 2), it is clearly visible that although the majority of PECs are located in the turnout range of 70% and above, about one third of the territories have polling stations with turnout around 60% and below. At the same time, PECs with a low value of the electoral indicator are located not only in the range between 2800 and 3400, which corresponds to the city of Perm, but are also found in the form of small clusters in other, but not in all, territories within the Krai.

Figure 2. Voter turnout in Perm Krai for the 2024 Russian Presidential Election by previously adopted TEC numbering (see interactive chart at https://public.tableau.com/shared/JM699HW4W?:display_count=n&:origin=viz_share_link). Each point corresponds to a specific PEC, which are grouped according to the previously adopted TEC numbering within the respective centesimal range. The PEC number begins with the number of the corresponding TEC

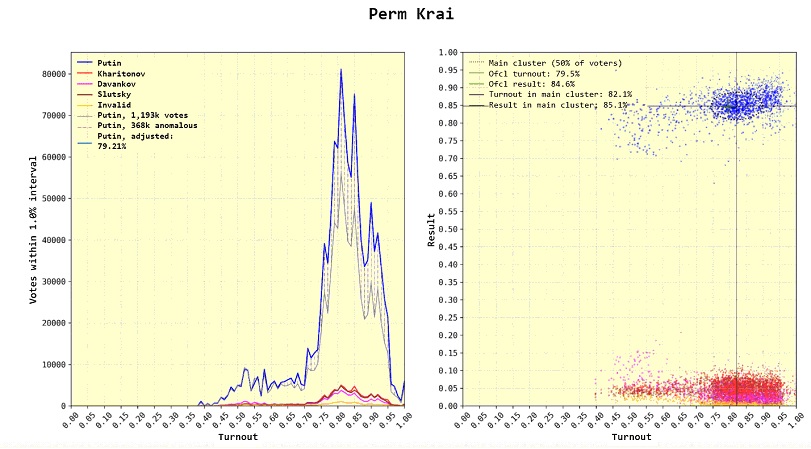

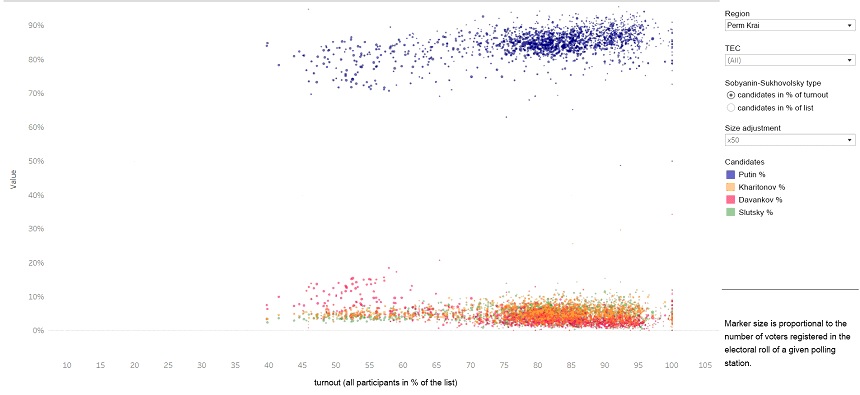

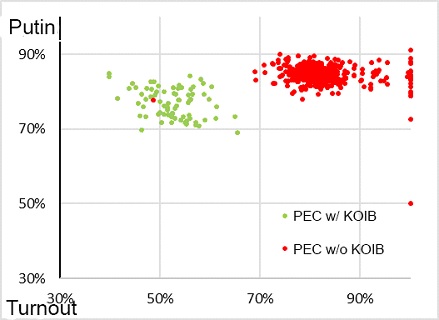

The diagrams constructed by independent experts using the Kiesling-Shpilkin method, as well as scatter diagrams (Figures 3 and 4), also demonstrate the division of Perm PECs into a main very dense cluster, where the winner and turnout results are very close to the official figures, and a scattered cloud of PECs with much lower values. Moreover, it can be seen that at the same polling stations, Davankov's results differ markedly from the results at PECs with higher turnout and scores for Putin.

Figure 3. Vote returns for the presidential election in Perm Krai processed using the Shpilkin method

Figure 4. Candidate results by turnout (see interactive chart at https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/roman.udot/viz/shared/Y8T3TM5K3)

Thanks to the Kiesling-Shpilkin method, which is believed to assess so-called "pure ballot stuffing" without taking into account other fraudulent methods, the data from the presidential election in Perm Krai drew the attention of analysts shortly after the official results were summarized. Ivan Shukshin, an independent election expert, pointed out the artificial nature of this result: "The fact that certain methods were used not to just doctor Putin's result, but also to push Davankov to third place, is evident in some regions. Perm Krai, for example. Take a look(Fig. 3 – K.V.) at the "cloud" of Davankov's purple dots on the right graph: he is above other candidates in the area of genuine turnout of 50% and is already below the red dots of the CPRF candidate in the area of fraudulent turnout of 80%" [15].

The overall image is that the bulk of PECs in Perm Krai showed results close to the national and regional average: turnout of around 80%, Vladimir Putin's result above 80% and nearly equal results of the other candidates of around 5%. Nevertheless, there is a discernible group of PECs with markedly different results. There are polling stations with relatively low turnout and relatively high results of Davankov in Perm, as well as in small towns of the Krai and even in rural areas; they are territorially adjacent to polling stations with noticeably higher turnout and relatively low results of Davankov.

Such clustering is most pronounced in the city of Perm.

There are a total of 406 permanent polling stations in Perm, which are distributed into two unequal clusters in a huddled manner (Fig. 5). The first ("smaller") cluster includes 76 PECs with turnout ranging between 38% and 65% (we will refer to them as "green precincts"), the other ("larger") cluster includes 331 PECs with turnout ranging between 69% and 95% ("red precincts"). Moreover, polling stations with low turnout and "high" results of Davankov are present in all seven administrative districts of the city and in all eight TECs — both in the central part of the city and in its remote areas, both in microdistricts with high-rise and low-rise buildings, both in modern residential complexes and those built during the Soviet era.

Figure 5. Two PEC clouds on the graph of the dependence of Putin's result on turnout in the city of Perm

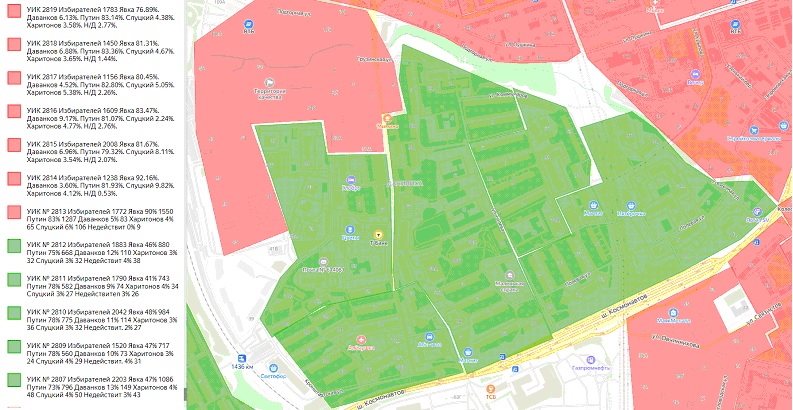

Let us look at one of Perm's microdistricts (Danilikha), which is part of the city's Dzerzhinsky District TEC as an example (Fig. 6). Six PECs with close numbers of voters (given in parentheses) were set up in the microdistrict: 2807 (2303), 2809 (1502), 2810 (2042), 2811 (1790), 2812 (1883), 2813 (1722). Five of them (highlighted in green) are located in School No. 25, and PEC No. 2813 (highlighted in red) is located in Gymnasium No. 4 together with the neighboring PEC No. 2814.

Figure 6. PEC of the Danilikha microdistrict of the city of Perm

Now, the Danilikha microdistrict is a rather homogenous residential area. As can be seen on the map, the southern boundary of PEC No. 2813 (where, incidentally, modern residential buildings are more numerous, compared to neighboring precincts) rather arbitrarily runs along the small roads that connect the yards of residential buildings in the microdistrict. Generic houses with similar resident groups (e.g., panel high-rises at 5 Gruzinskaya St. and 3 Gruzinskaya St.) were assigned to different PECs. Nevertheless, the results at these PECs are markedly different from each other. At the PECs highlighted in green, turnout did not exceed 48%. At PEC No. 2811 it amounted to only 41%, while the vote for Davankov amounted to between 9 and 12% and for Putin between 73 and 75%. PEC No. 2813, however, indicated a turnout of 90%, with Davankov gaining only 5% and Putin gaining 83%. Even more interesting is the difference in the number of invalid ballots: at the "red" PEC No. 2813 there are only 9, while at the "green" precincts the number varies between 26 and 43 (about 3-4%).

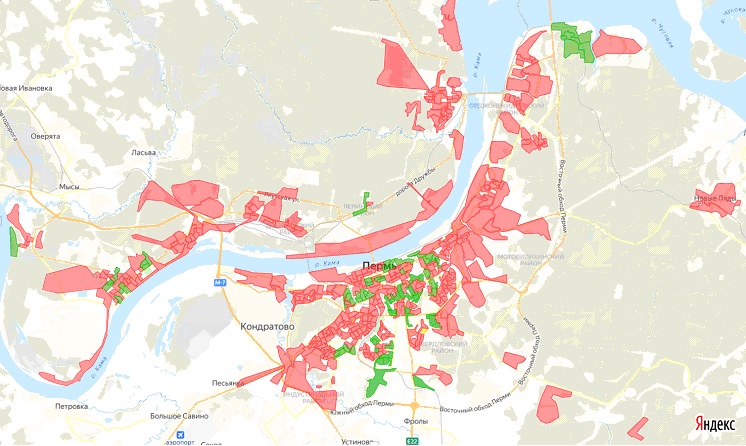

In general, presidential election results make almost the entire electoral map of Perm (Fig. 7) look like an archipelago of about 30 "green islands" scattered in different parts of the city, usually consisting of three to five tightly clustered polling stations with voting premises at the same address that is located in the middle of a "Red Sea" of polling stations with results close to the official ones.

Figure 7. Map of the boundaries and results of the Perm city electoral commissions in the 2024 presidential election (see interactive version of the map at https://yandex.ru/maps/?um=constructor%3Ab3aa51d0845f967f92b116b35edf7b512fe3cbac5786c34614c507a43d57299a&source=constructorLink)

A similar situation is observed in other territories of the Krai. "Green precincts" are clustered in certain TECs of the Krai (not even remotely in all of them), and their distribution both across the territory of the region and within the TECs has no connection whatsoever to the main socio-economic and demographic indicators of the residents.

How did these "green islands" originate, exactly? Why do the electoral indicators of these PECs differ markedly from those of other commissions? Do these differences lie in the behavior of voters or in the behavior of election administrators?

Research methodology: version, hypotheses, electoral data and methods of analysis

In order to understand the situation, we took the PECs of the regional capital Perm as a starting point, as this is where the largest concentration of "green precincts" is observed. A thorough examination of the 76 "green" PECs revealed only one parameter that unites almost all of them: 75 of these polling stations, in accordance with theResolution of the Perm Krai Election Commission No. 47/04-4 of February 9, 2024, were operating ballot paper processing systems (KOIB). The only polling station that does not meet this criterion is PEC No. 3470 (TEC Sverdlovskaya No. 1), which indicated a turnout of 48.67% (highlighted by the red dot in the green cloud in Fig. 5. and yellow color in the Fig. 7 map).

The principal difference between the use of PECs and manual counting of votes at the polling station is that the determination of the will of the voter and the tallying of all votes is carried out at the very moment of voting — the ballot paper is passed through the KOIB scanner. Members of commissions do not actually count votes at polling stations equipped with KOIBs. Their task is to ensure uninterrupted operation of the complex and, in accordance with the instructions, to initiate certain modes of operation of the KOIB in time. Thus, the KOIB is only a tool, like a calculator, in the hands of PEC members — a tool that has zero influence on the electoral behavior of voters, namely on their desire to come to vote (turnout) and on their intention to vote for this or that candidate (results of specific candidates).

In any case, the version that most "green precincts" with lower turnout and lower Putin's results, with higher Davankov's results, are polling stations equipped with KOIBs and therefore are less likely to have been exposed to external subjective influence, requires verification.

In this regard, we have put forward the following hypotheses:

— Voter activity and vote returns (turnout, number of votes for a candidate/party, place occupied, number of invalid ballots) do not depend on the way in which the votes are processed (by KOIB or by manual counting); otherwise it may indicate a distortion of the will of the voters, most likely committed during manual counting.

— Polling stations that are: a. located within the same constituency, b. include in electoral rolls residents of neighboring similar territories, c. represent similar social environments show similar results in different election campaigns, regardless of the way in which the votes are processed. In other circumstances, this may indicate a distortion of the will of the voters in the elections where such discrepancies were detected.

— The indicators of KOIB-equipped commissions can be more likely assessed as reliable, and their generalized data — broken down into metropolitan cities, small towns and rural areas — can be used for a rough assessment of the overall scale of distortions at the remaining polling stations and the distortion-free (normalized) results of the presidential election in the region.

This study's methodology is based on a comparative analysis of electoral data for the same polling stations obtained during several election campaigns. Arkadii Lyubarev drew attention to the prospects of such an approach in his work called "Entertaining Electoral Statistics", where he noted that "comparison of vote returns in elections of various years can be useful for identifying anomalies, especially in combination with the comparison of vote returns in different territories. If vote returns in a polling station (territory, region) differed little from its neighbors over the course of several elections, and then suddenly showed marked difference, this should be a serious reason for suspicion" [10: 52-53].

He also noted that "strong differences in vote returns at geographically close polling stations have long been a source of suspicions of manipulation" [10: 51] and calls attention to Nikita Shalayev's contribution of confirming intuitive ideas about this fact with the data of electoral statistics for a number of post-socialist countries and showing that the results of leading candidates and turnout at polling stations located at the same address showed less difference than those in the region as a whole [14: 120-131]. However, despite the significant success of local experts in quantitative research as a means of detecting electoral fraud, qualitative comparative electoral research is less popular among researchers. One of the few studies of this kind concerning KOIB-equiped polling stations in Moscow was carried out by Lyubarev, Buzin and Kynev back in 2007 [9]

Within the framework of this study that uses electoral data on the presidential election in Perm Krai, we focused on only one of the electoral tools — ballot paper processing system (KOIB). We analyzed the changes in how this tool is used in the elections in the region and the possibility of using the indicators recorded at KOIB-equiped polling stations to assess the official vote returns and the scale of distortion of the will of the voters.

Electoral indicators for the region recorded in SAS "Vybory" were processed by methods of comparative cross-territorial and cross-system analysis of electoral statistics separately for both KOIB-equipped polling stations and regular ones. The comparative analysis also took into account the location of polling stations: in the region's capital, in small towns and in rural areas.

The practice of using ballot paper processing systems (KOIBs) during elections in Perm Krai and its changes in 2024

A certain number of politicians, especially among representatives of the CPRF, as well as independent electoral experts and activist observers, were quite skeptical about KOIBs from the very moment they were introduced in the Russia's electoral intsitution. Their doubts were based on the fact that KOIBs do not eliminate the possibility of using multiple ballot-based fraud methods [9: 128], on the closed-source KOIB software, on the possibility of technical failures in their operation, as well as on the unnecessary restrictions that election organizers imposed for manual recounting of ballots [1], if such failures occurred or if election participants had doubts about their operation. Moreover, the use of KOIB giver rise to new ways of distorting the will of the voters [8]. A number of elections generated several high-profile stories associated with the use of KOIBs (e.g. the Primorsky Krai gubernatorial re-election on December 16, 2018).

According to the website of the Perm Krai Election Commission (PKEC) [4], 2011 was the year when KOIBs were used in the region for the first time. During federal and regional elections, the KOIBs were mainly installed in Perm. The Krai Election Commission predominantly adhered to the practice of compact distribution of KOIBs, preferring to cover almost all PECs of a given TEC with machines, except for temporary polling stations and polling stations with a small number of voters. For example, in the 2018 presidential election, 208 KOIBs were distributed among four TECs in Perm: 59 out of 64 PECs in Dzerzhinsky District, 60 out of 65 PECs in Industrial District, 21 out of 29 PECs in Leninsky District, and 65 out of 75 PECs in Motovilikhinsky District.

The year 2024 was the first time, in contrast to the long-standing practice of compactly distributing KOIBs to a few TECs in the presidential election, when the PKEC ordered several machines to be distributed across a wide range of territories in the region. The commission had 259 KOIBs at its disposal. According to the Resolution of the Perm Krai Election Commission No. 47/04-4 of February 9, 2024 [11], they were distributed from 3 to 30 pieces among the polling stations of 28 TECs of the region, where the total number of PECs amounts to 1226. There is no quantitative or qualitative logic as to why certain TECs and the number of PECs in them were chosen. Among them, there are territories where KOIBS had never been used before, as well as those where they had been used repeatedly, and, conversely, those TECs where KOIBs were actively used during previous campaigns were passed over. Among the selected territories there are ones located quite a long way from Perm.

The exclusivity of the dispersed and fractioned distribution of KOIBs in 2024, its fundamental difference from the previously existing and apparently ongoing (e.g. during the 2024 single voting day) practice, speaks to the purposefulness of this decision. All the more it speaks because installing KOIBs, preparing the necessary infrastructure, and training of commission members require special effort and additional expenses. It is more rational to equip more PECs with KOIBs at lower costs in a smaller number of territories, preferably adjacent to Perm.

In comparison with the previous election campaigns, the number of KOIBs used in 2024 was the largest, yet they covered the smallest number of voters in Perm Krai. For example, in the 2016 State Duma elections, 98 KOIBs covered 9.14% of voters, with an average of 1,942 voters per polling station; in the 2018 presidential elections, as many as 208 KOIBs covered 20.85% of voters, with an average of 1,988 voters per polling station; in the 2020 gubernatorial election the respective numbers were 215 KOIBs, 19.98% of voters, 1,857 on average; in the 2021 State Duma election — 219 KOIbs, 20.41% of voters, 1,853 on average; finally, the 2024 numbers amounted to 259 KOIBs covering only 17.74% of voters with an average of only 1,350 voters per polling station. According to the data of the Krai Election Commission as of January 1, 2024, about 80.5% of the voters of the entire Krai were registered in 28 TECs that were selected to be equipped with KOIBs [2]. However, in these territories, KOIBs covered only 24.5% of registered voters.

It is obvious that in 2024 the Election Commission was guided by a different logic of distributing KOIBs — a logic different from the previous desire to cover as many the polling stations in several TECs as possible, subsequently covering as many voters in the territory as possible.

The electorate of Perm Krai is divided into approximately three equal parts: voters of Perm, the capital of the region, voters of medium-sized and small towns of the Prikamye region (we will refer to them as "small towns" for brevity's sake), and rural voters. According to the protocols, residents of Perm amounted to about 35.5% of registered voters, residents of small towns and rural areas amounted to about 28.5% and 36%, respectively. PEC protocols recorded that in Perm, 75 KOIB-equipped PECs registered about 18.3% of the city's voters, 92 KOIB-equipped PECs in small towns registered about 31.4% of respective voters, and 92 KOIB-equipped PECs in rural settlements covered 27.7% of rural voters in the respective areas. It is unlikely that this was a random sample, but what was the purpose?

Voters in small towns of the Prikamye region were covered by KOIBs to the largest extent. KOIBs were installed in 12 out of 26 such towns, and overall reached 23.9% of voters in this type of settlement. However, they were distributed over the territories very unevenly. For example, in the second largest city of the region, Berezniki (about 92 thousand voters), KOIBs covered only 8.8% of voters, while 46.5% were covered in neighboring Solikamsk (about 57 thousand voters). Not a single KOIB was installed in the metal-producing town of Chusovoy (29.5 thousand), and all 8 KOIBs were installed in rural settlements. In Krasnokamsk (35,000), a satellite town of Perm, three KOIBs covered only 16.5% of voters, although the town had been covered almost completely by them many times before. At the same time, such small towns as Okhansk, Usolye with less than 5 thousand voters were completely covered by KOIBs. Chernushka with about 21 thousand voters was was covered at 90%.

It seems that the initiators and organizers of this scheme wanted to make the vote returns at KOIB-equipped polling stations less visible, to hide them in the general mass of polling stations with the traditional manual method of counting votes. The concentration, as previously practiced, of KOIBs in certain TECs, and then a possible significant discrepancy in the results between those TECs with KOIBs installed and those without them, especially in Perm, would inevitably catch the eye not only of specialists, but also of regular concerned voters and journalists. That is why, apparently, the decision was made to install more KOIBs outside Perm and a number of other cities in the Prikamye region.

In total, about 1 million voters were registered in the polling stations in Perm and small towns that remained outside the KOIB coverage.

However, the installation of KOIBs has its own technical limitations. They require reliable power supplies, and for ease of maintenance and uninterrupted operation it is more appropriate to install them in several polling stations located in one building rather than one polling station in several buildings. Among other requirements are transportation accessibility and relatively short distance of KOIB-equipped polling stations from TECs and/or offices of the servicing company. Hence the appearance of small groups of KOIB-equipped PECs, which create the very green islands with results different from the surrounding KOIB-free polling stations.

Analysis of discrepancies between the results of KOIB-equipped PECs and regular PECs in elections in Perm Krai

In very general terms, four indicators revealed marked discrepancies between polling stations with and without KOIBs (Table 1): turnout — discrepancies averaging about 20% for the entire region and almost 30% for Perm, Putin's result — by 5-7%, as well as twofold differences in Davankov's results and in the share of invalid ballots. Turnout and Putin's results are higher in "red precincts" without KOIBs, while Davankov's results and the number of invalid votes are higher in "green precincts" with KOIBs. The results of Kharitonov and Slutsky are not particularly different.

One could assume that the decrease in turnout and the increase in Davankov's performance are due to the contribution of the more critical voters in Perm, but the same logic of differences in results persists in polling stations with and without KOIBs in both small towns and rural areas, with the only difference being that the gaps shrink slightly.

Table 1. Comparison of results at polling stations with and without KOIBs in different territories of Perm Krai

| Perm Krai | Perm | Perm Krai without Perm | ||||

| without KOIBs | with KOIBs | without KOIBs | with KOIBs | without KOIBs | with KOIBs | |

| Number of KOIBs | 1527 | 259 | 358 | 75 | 1168 | 185 |

| Turnout | 83.79% | 62.18% | 81.73% | 52.32% | 85.18% | 67.90% |

| Putin | 85.34% | 80.75% | 84.64% | 77.27% | 85.79% | 82.30% |

| Kharitonov | 5.34% | 5.05% | 4.63% | 3.88% | 5.78% | 5.18% |

| Slutsky | 4.82% | 4.67% | 4.66% | 4.77% | 4.95% | 5.02% |

| Davankov | 3.53% | 6.97% | 4.78% | 10.79% | 2.72% | 5.27% |

| Invalid | 0.97% | 2.56% | 1.29% | 3.29% | 0.76% | 2.23% |

Did this type of significant discrepancy between polling stations with and without KOIBs occur in previous and subsequent elections? If we assume that the differences in the results at the polling stations with and without KOIBs recorded in the 2024 presidential election are not the result of intentional distortions, but demonstrate objective differences in the electoral preferences of Perm voters, then they should have manifested in the previous elections as well.

We were able to collect and analyze data from polling stations with and without KOIBs from presidential, parliamentary and gubernatorial elections in the region since 2012. No significant discrepancies that resembled the 2024 discrepancies were identified (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of results at polling stations with and without KOIBs in different elections in Perm Krai

| elections / placement of KOIBs | number of KOIBs | turnout | leader | LDPR | CPRF | AJR | democr | invalid | |

| President 2012 / Industrial. Leninsky. Sverdlovsky Districts of Perm | PK w/o KOIBs | 1795 | 54.99% | 63.72% | 4.70% | 15.70% | 4.37% | 10.16% | 1.36% |

| KOIBs Perm | 95 | 56.35% | 54.97% | 3.67% | 16.61% | 4.72% | 18.02% | 2.01% | |

| Perm w/o KOIBs | 342 | 55.92% | 57.53% | 4.24% | 16.80% | 4.68% | 15.08% | 1.66% | |

| State Duma 2016 Sverdlovsky. Leninsky. Motovilikhinsky Districts of Perm | PK w/o KOIBs | 1740 | 35.30% | 43.15% | 16.03% | 14.28% | 8.94% | 2.72% | 4.23% |

| KOIB | 98 | 33.88% | 37.48% | 12.93% | 13.81% | 9.92% | 6.71% | 4.07% | |

| Perm w/o KOIBs | 337 | 35.28% | 39.68% | 13.09% | 13.83% | 11.24% | 5.18% | 4.44% | |

| Perm Krai Governor 2017 / Dzerzhinsky District of Perm. Krasnokamsky MR | PK w/o KOIBs | 1746 | 36.70% | 80.29% | 4.18% | 8.28% | 3.33% | 1.97% | |

| KOIB | 94 | 43.09% | 82.20% | 3.72% | 7.43% | 2.77% | 2.33% | ||

| KOIBs Perm | 59 | 38.50% | 79.81% | 4.37% | 7.94% | 3.68% | 2.09% | ||

| Perm w/o KOIBs | 374 | 37.67% | 78.79% | 4.55% | 8.12% | 3.97% | 2.32% | ||

| President 2018 / Industrial. Dzerzhinsky. Leninsky. Motovilikhinsky Districts of Perm | PK w/o KOIBs | 1636 | 67.30% | 75.67% | 7.19% | 10.65% | 3.62% | 1.39% | |

| KOIB | 208 | 63.26% | 74.06% | 5.42% | 10.12% | 3.62% | 1.34% | ||

| Perm w/o KOIBs | 179 | 65.32% | 75.16% | 6.34% | 9.82% | 5.60% | 1.45% | ||

| Perm Krai Governor 2020 / Dzerzhinsky. Industrialny. Kirovsky Districts of Perm. Krasnokamsky and Vereshchaginsky Urban Districts | PK w/o KOIBs | 1585 | 37.89% | 78.41% | 5.60% | 13.52% | 2.73% | ||

| KOIB | 213 | 27.24% | 74.28% | 7.02% | 16.63% | 2.32% | |||

| KOIBs Perm | 173 | 27.02% | 73.51% | 7.53% | 16.87% | 2.33% | |||

| Perm w/o KOIBs | 258 | 28.79% | 73.52% | 7.64% | 16.52% | 2.46% | |||

| State Duma 2021 / Dzerzhinsky. Industrialny. Leninsky Districts of Perm. Krasnokamskiy Urban District | PK w/o KOIBs | 1570 | 35.30% | 34.03% | 10.39% | 22.57% | 10.91% | 8.09% | 4.87% |

| KOIB | 219 | 33.88% | 31.47% | 7.43% | 23.56% | 10.26% | 11.08% | 4.16% |

The table is not fully displayed Show table

For the convenience of displaying data in a single table, we grouped a number of indicators: all candidates and parties of power were labeled as "leader", communists in party elections and their nominees in elections of officials as "CPRF", liberal-democrats as "LDPR"; "A Just Russia", parties and candidates who positioned themselves as representatives of the democratic opposition were similarly labeled as "democrats". In some cases, such as in the 2018 presidential election, the "democrats" combined the results of several candidates (Sobchak, Titov, Yavlinsky); in others, the contestants with the best results were chosen (New People in 2021). The results of parties and candidates who acted as spoilers (e.g., Communists of Russia), technical candidates, or at the level of "electoral noise" were not included in the calculations.

Since in most cases KOIBs were installed at PECs in Perm, we compared their results not only with the data for the region, but, more correctly, with the results at other polling stations in the capital not equipped with KOIBs. In cases where KOIBs were also installed outside the city of Perm, two pairs of comparisons were obtained — separately for Perm Krai (PK) and for Perm.

Only the following can be noted if the relatively observable differences between the results at polling stations with and without KOIBs:

— in 2012 and 2016, polling stations with KOIBs showed a slightly lower result for the "leader" and a higher result for the conventional "democratic candidate" (Prokhorov, Yabloko) than at other PECs; this is due to the fact that all KOIBs were installed in Perm, where, like in other metropolitan cities, the democratic electorate is more represented and, on the contrary, the LDPR electorate is less represented;

— In Perm, the results of candidates and parties at polling stations with and without KOIBs are practically indistinguishable;

— then again, lower activity of the urban electorate explains the usual 2-3% decrease in turnout compared to polling stations without KOIBs; only in 2020, in the less competitive gubernatorial election, the discrepancy reached 10%;

— In fact, the invalid ballot rates have nothing to do with KOIB installation, but only vary from campaign to campaign.

The main thing is the absence of any observable differences between the results at polling stations with and without KOIBs in Perm, where the systems were regularly used, covering entire administrative districts.

Thus, for many years using KOIBs in Perm Krai did not yield any cases when vote returns at polling stations with and without KOIBs differed significantly from each other. Few percent differences are explained by repeatedly recorded and described differences in electoral preferences between voters in large cities, small towns and rural areas. Naturally, there are always polling stations with higher or lower indicators in any election, but it depends both on the peculiarities of a given voter group (e.g., a high share of students, pensioners, employees of some enterprise, etc.) and on situational factors (e.g., successful mobilization efforts of administrations, campaigners, social and domestic issues of residents, etc.). However, Perm does not know such examples so that the activity and preferences among the voters of one relatively homogeneous territory correlate only with the way their votes are counted.

Another point that draws attention is the discrepancy in one more symbolically significant election result — the rating of candidates. While Vladimir Putin's lead was indisputable, there remained some intrigue as to which of the remaining candidates would come in second place. According to this indicator, the polling stations with and without KOIBs also show very significant differences, primarily among Perm voters (Table 3). The most significantly different is the average rating of Davankov. In 75 polling stations with KOIBs he was ranked as a strong 2nd in 100% of cases (at one of the polling stations Davankov and Kharitonov showed exactly the same results), but in the remaining 358 polling stations without KOIBs he was ranked 2nd in only 33% of cases. On the contrary, Slutsky, who came in second place more often in polling stations without KOIBs, confidently took 4th place in polling stations without KOIBs.

Table 3. Average rating of candidates at PECs in Perm

| Davankov | Slutsky | Kharitonov | |||||||

| PEC | with KOIBs | without KOIBs | with KOIBs | without KOIBs | with KOIBs | without KOIBs | |||

| average rating | 2.00 | 2.92 | 3.84 | 3.03 | 3.10 | 2.99 | |||

| 2nd place | 100% | 33% | 0% | 37% | 1% | 33% | |||

| 3rd place | 0% | 43% | 20% | 23% | 83% | 35% | |||

| 4th place | 0% | 25% | 77% | 40% | 15% | 32% | |||

It seems highly doubtful that the preferences of opposition-minded voters fluctuated so markedly from microdistrict to microdistrict within the same territory. Even at those Perm polling stations with KOIBs, where voters demonstrated a high turnout, which can be generally regarded as a manifestation of loyalty (to the government, to the elections, to the administration), Davankov retained 2nd place.

In the KOIB-equipped TECs outside Perm the situation is more complicated due to the naturally greater heterogeneity of the territories themselves and the voters residing in them (Table 4). Nevertheless, in polling stations with KOIBs, Davankov came second in about 43% of cases, and in polling stations without KOIBs only in 4%. On the contrary, Kharitonov's rating in polling stations without KOIBs is almost a mirror image of Davankov's rating, while the results of all three candidates in polling stations with KOIBs look relatively level.

Table 4. Candidate ranking at PECs outside Perm

| Davankov | Slutsky | Kharitonov | ||||

| PEC | with KOIBs | without KOIBs | with KOIBs | without KOIBs | with KOIBs | without KOIBs |

| average rating | 2.90 | 3.53 | 3.06 | 3.05 | 2.92 | 2.30 |

| 2nd place | 42.67% | 4.00% | 30.67% | 22.67% | 34.67% | 78.67% |

| 3rd place | 30.67% | 18.67% | 40.00% | 61.33% | 29.33% | 16.00% |

| 4th place | 26.67% | 76.00% | 28.00% | 14.67% | 33.33% | 4.00% |

This again cannot but suggest that the fabricated nature of results at the polling stations not equipped with KOIBs and that their purpose was to reduce Davankov's rating, making it as low as possible. As a result, the New People candidate dropped to 4th place in the final tally, with only a few tenths of a percent difference between the three candidates.

If we go even further down to the administrative level, yet again we see differences in the results at polling stations depending on the installation of KOIBs, both at the level of municipalities as a whole and within them. As at the regional level, they hardly have anything to do with candidates Kharitonov and Slutsky. The difference between their indicators at polling stations with and without KOIBs rarely reaches more than 1.5% modulo, and there is barely any logic to it. The rest of the electoral indicators (turnout, share of Putin's and Davankov's votes, share of invalid ballots) are quite stable and vary considerably.

These differences are most indicative in Perm (Table 5), where, let us recall, KOIBs were dispersed throughout all seven administrative districts in small clusters, not even fully covering the microdistricts.

Table 5. Comparison of results at polling stations with and without KOIBs by Perm administrative districts

| TEC | number of KOIBs | turnout | Putin | Davankov | invalid | |

| Dzerzhinsky | KOIB | 8 | 48.06% | 75.19% | 12.53% | 3.93% |

| without KOIBs | 56 | 83.70% | 84.58% | 5.17% | 1.20% | |

| difference | 35.64% | 9.38% | -7.36% | -2.73% | ||

| Leninsky | KOIB | 9 | 55.14% | 72.98% | 14.63% | 4.22% |

| without KOIBs | 20 | 81.04% | 83.22% | 6.68% | 1.26% | |

| difference | 25.90% | 10.25% | -7.95% | -2.96% | ||

| Motovilikhinsky | KOIB | 10 | 51.41% | 74.72% | 12.67% | 3.39% |

| without KOIBs | 65 | 80.75% | 84.15% | 4.84% | 1.36% | |

| difference | 29.34% | 9.44% | -7.83% | -2.03% | ||

| Industrialny | KOIB | 5 | 53.97% | 81.28% | 8.12% | 2.43% |

| without KOIBs | 60 | 80.24% | 85.26% | 5.21% | 1.26% | |

| difference | 26.27% | 3.98% | -2.91% | -1.17% | ||

| Ordzhonikidzevsky | KOIB | 3 | 58.24% | 85.53% | 5.93% | 2.99% |

| without KOIBs | 51 | 82.92% | 85.22% | 4.08% | 1.24% | |

| difference | 24.68% | -0.31% | -1.85% | -1.75% | ||

| Sverdlovsky No. 1 and No. 2 | KOIB | 30 | 53.28% | 76.76% | 11.07% | 3.33% |

| without KOIBs | 61 | 81.15% | 84.74% | 4.99% | 1.48% | |

| difference | 27.87% | 7.99% | -6.08% | -1.85% | ||

| Kirovsky | KOIB | 10 | 49.24% | 81.18% | 7.71% | 2.56% |

The table is not fully displayed Show table

It is impossible to find objective reasons that would explain why voter turnout in these green clusters is so markedly different (by 25-35%) in neighboring microdistricts or even within the same one. There is only one case that, in our opinion, has objective reasons to explain the difference between the candidate performance: it is three polling stations with KOIBs in Ordzhonikidzevsky District of Perm (Nos. 3325, 3326, 3327). These stations are located in a rather remote from the center and relatively isolated Golovanovo microdistrict established around a paper mill. The voting premises of all three PECs are located at the same address in the Bumazhnik Community Center. For many years, the enterprise has been headed by one of the leaders of the Perm's United Russia cell. Naturally, there are many factory employees among the voters of the microdistrict. Accordingly, Putin's high result (about 85%) even with a relatively low turnout (about 58%) may well be explainable. However, the turnout here is still about 25% lower than that reported by the district's TEC in its final protocol and demonstrated by several other similar neighboring microdistricts of Ordzhonikidzevsky District of Perm.

In large cities, small territorial communities with distinctive ethnic, religious, age, professional and other composition may form, and they may behave differently during elections, but, as far as we know, there are no such isolated homogeneous communities of several thousand people (the number of voters of three or four PECs) in Perm. At least they are not in those "green clusters" that demonstrated significantly less electoral activity and loyalty compared to other microdistricts of the city.

Again, there are similar green islands outside of Perm, in other territories where KOIBs were installed, including in rural areas, i.e. this is not a characteristic of voters in the capital.

Cross-territorial and cross-temporal comparison of electoral data

We were able to identify three types of KOIB distribution patterns by TEC territories: "urban", "rural", "mixed".

Under the "urban scheme", KOIBs were installed predominantly in the urban administrative center of the district: in one of the small towns of the Prikamye region. Such territories include the Solikamsky Urban District (UD), where all 15 KOIBs were installed in Solikamsk itself, the Chernushinsky UD (all 16 installed in Chernushka), the Osinsky UD (all 5 installed in Osa), the Dobryansk UD (4 installed in Dobryanka), the Vereshchaginsky UD (7 installed in Vereshchagino), the Okhansky UD (4 installed in Okhansk), and the Nytvinsky UD (6 installed in Nytva). Consequently, under this scheme, we can compare the results at polling stations with and without KOIBs both between the urban and rural parts of the local electorate, and within the small town itself.

Under the "rural scheme", KOIBs were installed either in the administrative center, which does not have the status of a city, and in other rural settlements (Uinsky, Yelovsky, Kishertsky, Oktyabrsky, Ordinsky, Permsky, Berezovsky, Suksunsky Municipal Districts), or outside the small town, only in villages surrounding it. This was the case in the Chusovsky UD, where the core is the metal-producing town of Chusovoy, but all eight KOIBs were distributed to villages. In this case, we can compare electoral data for rural voters only.

In the "mixed scheme", KOIBs were distributed both to the urban center of the territory and in rural settlements. The proportions between conventionally 'urban' and 'rural' KOIBs varied, but overall this gives a balanced impression of the true sentiments of both small town and rural voters. Such a scheme was applied in the following territories: Kungursky UD (10 KOIBs in Kungur and 14 in villages), Bereznikovsky UD (3 in Berezniki, 1 in Usolye, 9 in villages), Chaikovsky UD (15 in Chaikovsky and 4 in villages), Krasnokamsky UD (3 in Krasnokamsk and 3 in villages). Under this scheme, we can compare polling stations with and without KOIBs within the city, in rural areas, and among the polling stations themselves.

We shall avoid overburdening the text with comparative tables and graphs and only give conclusions based on the results obtained.

Similarly to the situation in Perm, regardless of the layout, in absolutely all cases on average across the territory, polling stations with KOIBs demonstrate an evidently lower turnout than polling stations without KOIBs. The difference is that, as a rule, KOIBs in small towns record, on average, a slightly higher turnout than in Perm, and a higher turnout in rural areas than in small towns. The difference in turnout rates between "machine" and "manual" polling stations is more contrasting in urban areas than in rural areas. The gaps in the turnout approved by the commissions are smaller when the turnout demonstrated by voters in polling stations with KOIBs is higher. It is interesting that one of the highest gaps (35%) was demonstrated by a TEC in the Okhansky District, one of the most sparsely populated districts in Perm Krai (only 10,000 voters): four polling stations with KOIBs in Okhansk itself recorded an average turnout of 56%, while seven rural polling stations recorded an average turnout of 91%.

The polling stations with KOIBs confirm that Putin has a consistently high rating among loyal voters who came to the polls, both in small towns of the Prikamye region and in rural areas — from 78% and above. In Perm, Putin received 77.3% at polling stations with KOIBs.

Nevertheless, Davankov managed to take the 2nd place more often in small towns and less often in rural areas when it came to polling stations with KOIBs. In polling stations without KOIBs he did not manage to get it even once.

The ratings of Putin's competitors at KOIB-equipped polling stations vary from territory to territory. There was no 100% dominance of Davankov for second place like there was in Perm. However, at polling stations without KOIBs, the second place most often went to Communist candidate Kharitonov.

Just as in Perm, in each of the territories, the average percentage of invalid ballots at polling stations with KOIBs was usually twice as high as in polling stations without KOIBs, tended to 2% and higher (i.e., there was almost no difference from Perm polling stations), while at polling stations without PECs it amounted to only about 0.5-0.7%.

Overall, the results at polling stations with KOIBs in Perm Krai are in line with pre-election expectations and previous election campaigns. Loyalist voting is higher among rural voters and small town voters; on the contrary, protest electoral behavior is evidently higher in Perm. The protest was expressed not only through non-participation or in votes for Davankov, but also in spoiling ballots. In Perm, the turnout at the 75 polling stations with KOIBs (52.3%) was even lower than in the most active election in Perm Krai up to that point — the 2018 presidential election (64.3%).

Table 6. Results at polling stations with KOIBs by type of territory

| Number of PECs with KOIBs | Number of voters at polling stations with KOIBs | Share of the covered category of voters | Turnout | Putin | Davankov | Slutsky | Kharitonov | Invalid | |

| Perm | 75 | 127972 | 18.31% | 52.32% | 77.27% | 10.79% | 3.88% | 4.77% | 3.29% |

| Small towns | 92 | 133897 | 23.89% | 65.89% | 82.42% | 5.42% | 4.82% | 4.94% | 2.39% |

| Rural settlements | 92 | 87673 | 17.06% | 70.89% | 82.12% | 4.99% | 5.29% | 5.50% | 2.03% |

| Perm Krai | 259 | 349542 | 19.71% | 62.18% | 80.75% | 6.97% | 4.67% | 5.05% | 2.56% |

Were there cases of such significant discrepancies in neighboring polling stations in previous instances of using KOIBs in the region? A cross-country comparison of the results chains at the same PECs over several elections may provide an answer to this question. Unfortunately, there were not many such cases.

As an example, we can cite polling stations Nos. 2807, 2809, 2810, 2811, 2812, 2813 of the above-mentioned Danilikha Microdistrict of Perm. In 2024, the no-KOIB PEC No. 2813, recorded a turnout of 90.07%, while other polling stations with KOIBs recorded turnout between 41.51% and 49.19%. In the elections that took place between 2017 and 2021, all 6 polling stations had KOIBs installed, while none had in the 2016 legislative election and the 2012 presidential elections of 2012. And in all cases, voter turnout in all six polling stations was fairly close: a standard deviation of 2 to 5%, but it does not compare favorably to the 2024 gap. A similar situation developed around other "green islands" in Perm.

In Krasnokamsk, where KOIBs were repeatedly installed during several election campaigns, two polling stations located in the same building of school No. 10 and including neighboring addresses indicated completely different turnout levels: 51.3% at the KOIB-equipped PEC No. 1712, and 82.64% at the PEC No. 1713. Meanwhile, in all previous elections, their figures were very close regardless of whether or not they had KOIBs installed. In 2018, neither polling station was equipped with KOIB, but nevertheless showed almost identical turnout — 63.8% and 63.2% respectively.

Outside of federal and regional election campaigns, KOIBs are used in local elections on single voting days. It is not quite correct to compare their results with higher-level elections, but one cannot but notice that in general the voters of a certain territory show quite the same reaction to this or that campaign. If elections generate interest, both polling stations with and without KOIBs show an increase in turnout and similar results. If voters are not interested in an election, turnout drops at all polling stations, regardless of how votes are counted there. No cases similar to the situation in spring 2024 were identified.

Normalized results and conclusions

As we pointed out before, the official responsible for distributing PECs across Perm Krai did it based on the sociological sampling of different parts of the Perm electorate. If we build a model of voting (taking into account the ratio of metropolitan, urban and rural parts) at polling stations with KOIBs in the context of these territories, first for the remaining polling stations not covered by KOIBs, and then (taking into account the indicators already cleared of anomalies) for the whole krai, the turnout (according to paper voting) for Perm Krai should have been about 60.4%, Putin's result would have amounted to 82.4%, Davankov's to 7.8%, Slutsky's to 4.7%, Kharitonov's to 4.8%. The official vote returns of paper voting were as follows: turnout 79.5%, Putin 84.6%, Slutsky 4.8%, Kharitonov 5.3%, Davankov 4.1%. The difference corresponds to about 340 thousand extra votes manifesting in the protocols; most of these votes went to the incumbent president (about 312 thousand). At the same time, Davankov apparently lost about 26,000 votes. Kharitonov supposedly received about 23 thousand extra votes, and Slutsky received more than 17 thousand. The number of invalid ballots decreased by about 11,500. Overall, this is quite close to those estimates of anomalous votes, which, according to Shpilkin method, estimate the array of anomalous votes at 368,000, and model Putin's actual result at 79.2%.

Taking into REV account, whose results, curiously enough, are quite close to the clean data (Putin 84.75%, Davankov 8.15%, Slutsky 4.71%, Kharitonov 2.38%), the normalized result of the presidential election in Perm Krai was supposedly as follows: 63.6% for turnout, 84.6% for Putin, 8% for Davankov, 4.8% for Slutsky, 4.6% for Kharitonov, 2.3% for invalid ballots.

As Arkadii Lyubarev and other colleagues point out, calculations should be supported by relevant evidence from observations at polling stations [10: 95]. However, there may be cases where the mere absence of such evidence and public information from PECs may support doubts about the official results. As far as we know, during the voting days in Perm Krai, almost all the few activists who turned out to be observers were denied copies of protocols from polling stations. Observers from the Civic Chamber were instructed to leave the polling stations before vote counting began. During all voting days, the commissions tried not to publicly announce the turnout at polling stations. PEC protocol data were not entered into the larger protocol forms at the TECs. Several observers were denied access to video footage from polling stations recording the counting, which could have been used to establish the actual figures obtained by the commissions. It can be assumed that the distortion of results at polling stations without KOIBs occurred during the submission of protocols to TECs and data entry into SAS "Vybory".

In conclusion, we may say that the hypotheses we put forward were confirmed and the discrepancies revealed between the official vote returns at the polling stations with and without KOIBs at the Russian Presidential election in Perm Krai are not objective and result from subjective interference. These discrepancies are a one-off case in the long-standing use of KOIBs in Perm. The purpose of this intervention was to achieve a symbolically meaningful outcome. One of the ways to achieve it was to change the practice of using technical means of vote counting; that is, to remove the factor that restrains and limits the direct rewriting of protocols in Perm before all else and other urban areas in the Prikamye.

The political result of the former election, even that which is free of the anomalies of polling stations without KOIBs, leaves no doubt in determining the winner of the said election (even with a turnout of 62%, Putin would have won 80% of the Perm vote). However, it could no longer satisfy the government, who needed a demonstration of absolute loyalty and support, which now makes Perm Krai one of the "red" regions, where the official results differ greatly from the actual expression of the will of the voters. The presence of "green islands" of different results is only a consequence of the forced use of KOIBs. It is likely the commissions at these polling stations simply got lucky. They found themselves shielded from external pressure by a technical factor. The true heroes were the members of that dozen commissions with manual vote counting, who recorded results close to those yielded by KOIBs without the technical protection of the former.

In the long run, green islands leave an opportunity, albeit limited, to study some characteristics and dynamics of electoral and political preferences of voters. It is possible to conduct a comparative study using data from KOIB-equipped polling stations in other regions. "Red zones" on the electoral map of the region are a subject for studying the features, mechanisms and effectiveness of regional management of electoral results. They say little about voter sentiments, highlighting sentiments of the elites instead.

The research was carried out as part of the state assignment (subject No. 124021400020-6, "Multilevel Politics in the Modern World: Institutional and Socio-Cultural Dimensions").

Received 08.10.2024, revision received 01.11.2024.

References

- Buzin A.Yu. On Manual Recounting of Ballots from Ballot Paper Processing Systems (KOIB). – Electoral Politics. 2019. No. 2. P. 3. - https://electoralpolitics.org/en/articles/o-kontrolnom-ruchnom-podschete-golosov-pri-primenenii-kompleksov-obrabotki-izbiratelnykh-biulletenei-koib/

- Chislennost izbiratelei, uchastnikov referenduma, zaregestrirovannykh na territorii Permskogo kraya po sostoyaniyu na 1 yanvarya 2024 goda [The Number of Voters, Referendum Participants Registered in Perm Krai as of January 1, 2024]. – Website of the Perm Krai Election Commission. URL: http://permkrai.izbirkom.ru/chislennost-izbirateley/po-sostoyaniyu-na-1-yanvarya-2024-goda.php (accessed 07.10.2024). (In Russ.) - http://permkrai.izbirkom.ru/chislennost-izbirateley/po-sostoyaniyu-na-1-yanvarya-2024-goda.php

- Golosov G.V. Chestnost vyborov i yavka izbiratelei v usloviyakh avtoritarizma [Election Integrity and Voter Turnout Under Authoritarianism]. – Political Science (RU). 2019. No. 1. P. 67-89. DOI: 10.31249/poln/2019.01.04 (In Russ.)

- Ispolzovaniye KOIB i videonablyudeniya [Use of KOIB and Video Surveillance]. – Website of the Perm Krai Election Commission. URL: http://permkrai.izbirkom.ru/ispolzovannie-pri-golosovanii-na-vyborakh-referendumakh-kompleksov-obrabotki-izbiratelnykh-byulleten/ (accessed 07.10.2024). (In Russ.) - http://permkrai.izbirkom.ru/ispolzovannie-pri-golosovanii-na-vyborakh-referendumakh-kompleksov-obrabotki-izbiratelnykh-byulleten/

- Khokhlov B. Kak i skolko "narisovali" na golosovanii po popravkam k Konstitutsii RF v Permi ["Doctored" Votes in Russia's Constitutional Referendum in Perm: How Many There Were and How They Came to Be]. – Website of the "Golos" Movement (included in the register of foreign agents), 09.07.2020. URL: https://golosinfo.org/articles/144501 (accessed 07.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://golosinfo.org/articles/144501

- Kovin V. Obnuleniye izbiratelnoi sistemy v Permi, ili "Kazus Ordzhonikidzevskogo. Gipoteza" ["Zeroing Out" the Electoral System in Perm, or "The Case of Ordzhonikidzevsky. A Hypothesis."]. – Golos Movement Website (included in the register of foreign agents), 17.07.2020. URL: https://golosinfo.org/articles/144526 (accessed 07.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://golosinfo.org/articles/144526

- Kovin V. Permskiy krai: dvoika po elektoralnoi arifmetike [Perm Krai Gets a Failing Grade in Electoral Arithmetic. – Golos Movement Website (included in the register of foreign agents), 23.12.2020. URL: https://golosinfo.org/articles/144960 (accessed 07.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://golosinfo.org/articles/144960

- Kravchenko O.A. Tipy iskazheniya voleizyavleniya izbiratelei pri elektronnom golosovanii [Types of Distortion of the Will of Voters in E-Voting]. – Academic Law Journal. 2018. No. 1 (71). P. 15-25. (In Russ.)

- Lyubarev A.E., Buzin A.Yu., Kynev A.V. Myortvye dushi. Metody falsifikatsii itogov golosovaniya i borba s nimi [Dead Souls. Methods of Manipulating Vote Returns and Means of Сombating Them]. Moscow, 2007. (In Russ.)

- Lyubarev A.E. Zanimatelnaya elektoralnaya statistika [Entertaining Election Statistics]. Moscow: Golos Consulting, 2021. 304 p. (In Russ.)

- Ob ispolzovanii pri golosovanii na vyborakh Prezidenta Rossiyskoi Federatsii, naznachennykh na 17 marta 2024 goda, tekhnicheskikh sredstv podscheta golosov – kompleksov obrabotki izbiratelnykh byulleteney [On the Use of Hardware and Software Tools (Ballot Processing Complexes) for Voting it the Election of the President of the Russian Federation Scheduled for March 17, 2024. - Website of the Perm Krai Election Commission. URL: http://permkrai.izbirkom.ru/dokumenty-ik/postanovleniya-ikpk/2024/47_09022024/47_04_09.02.2024.docx (accessed 07.10.24). (In Russ.) - http://permkrai.izbirkom.ru/dokumenty-ik/postanovleniya-ikpk/2024/47_09022024/47_04_09.02.2024.docx

- O rezultatakh vyborov Prezidenta Rossiyskoi Federatsii, naznachennykh na 17 marta 2024 goda [On the Results of the Election of the President of the Russian Federation Scheduled for March 17, 2024]. Postanovleniye No. 163/1291-8 ot 21 marta 2024 g. [Resolution No. 163/1291-8 of March 21, 2024]. – The CEC of Russia website. URL: http://www.cikrf.ru/analog/prezidentskiye-vybory-2024/p_itogi/ (accessed 07.10.2024). (In Russ.) - http://www.cikrf.ru/analog/prezidentskiye-vybory-2024/p_itogi/

- Schedler A. The nested game of democratization by elections. – International political science review. 2002. Vol. 23. No. 1. P. 103–122.

- Shalaev N.E. Elektoralnyye anomalii v postsotsialisticheskom prostranstve: opyt statisticheskogo analiza [Electoral Anomalies in the Post-Socialist Space as Evidenced by Statistical Analysis]. Diss. for a PhD in Political Science. St. Petersburg: SPbSU, 2016. 191 p. (In Russ.)

- Shukshin I. Putiny vbrosili bespretsendentnyye 22 mln golosov na vyborakh 2024 [An Unprecedented 22 Million Ballots Stuffed for Putin in the 2024 Election]. – Golos Movement Website (included in the register of foreign agents), 18.03.2024. URL: https://golosinfo.org/articles/146796 (accessed 07.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://golosinfo.org/articles/146796

- TsIK: yavka na vybory prezidenta v Permskom kraye sostavit 82-85% [The CEC: Projected Turnout for the Presidential Election in Perm Krai is 82-85%. - RBK, 01.03.2024. URL: https://perm.rbc.ru/perm/freenews/65e18af69a79473e35f328d1?from=copy (accessed 07.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://perm.rbc.ru/perm/freenews/65e18af69a79473e35f328d1?from=copy

- Vybory Prezidenta 2024: ozhidayemye rezultaty [Presidential Election 2024: projected results]. – VCIOM website, 11.03.2024. URL: https://wciom.ru/analytical-reviews/analiticheskii-obzor/vybory-prezidenta-2024-ozhidaemye-rezultaty (accessed 07.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://wciom.ru/analytical-reviews/analiticheskii-obzor/vybory-prezidenta-2024-ozhidaemye-rezultaty

- Vybory Prezidenta Rossiyskoi Federatsii [Election of the President of the Russian Federation]. Perm Krai. – Website of the CEC of Russia. URL: http://www.permkrai.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/permkrai?action=show&root=1&tvd=100100339411275&vrn=100100339410030®ion=90&global=&sub_region=90&prver=0&pronetvd=null&vibid=100100339411275&type=226 (accessed 07.10.2024). - http://www.permkrai.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/permkrai?action=show&root=1&tvd=100100339411275&vrn=100100339410030®ion=90&global=&sub_region=90&prver=0&pronetvd=null&vibid=100100339411275&type=226