Resealable security bag

Abstract

A tamper-evident security bag must show visible traces of unauthorised access to its contents. This work demonstrates a method to install a backdoor to the bag’s tamper-proofing mechanism by coating it in advance with a transparent silicone layer under its indicating sealing tape. This prevents the tape’s permanent adhesion and allows the sealed bag to be opened and resealed without leaving any clues or changes in its visual appearance. This vulnerability allows individuals procuring and using the bag within a larger organisation to circumvent its security. For instance, in Russian multiple-day elections, these bags store uncounted ballots and are routinely tampered with. The adoption of a better use protocol may mitigate this risk.

Introduction

Tamper-indicating seals have been known since antiquity and are widespread today [7; 14]. In order for the seal to be an effective security measure for any high-value asset, all interested parties require formal training and should adhere to a detailed use protocol [2; 8]. In this work, I investigate commonly available plastic security bags that use an indicating sealing tape. The principle of the security bag is that any attempt to access its contents should leave visible traces on the bag. The bags are used widely in commerce, banking, airport security, gambling industry, laboratories, law enforcement and courts for transporting and storing valuables, samples, evidence, genuine items, and documents.

During recent Russian elections, resealable security bags used for “secure” storage of ballots were filmed by observers [18; 21], while an anonymous journalistic source confirmed their presence among election commissions [3] without revealing how the tampering was done. I independently reproduced these results. The cited reports may be the tip of the iceberg, as most tampering incidents probably remain undetected during elections and in other applications of these bags.

Bags under test

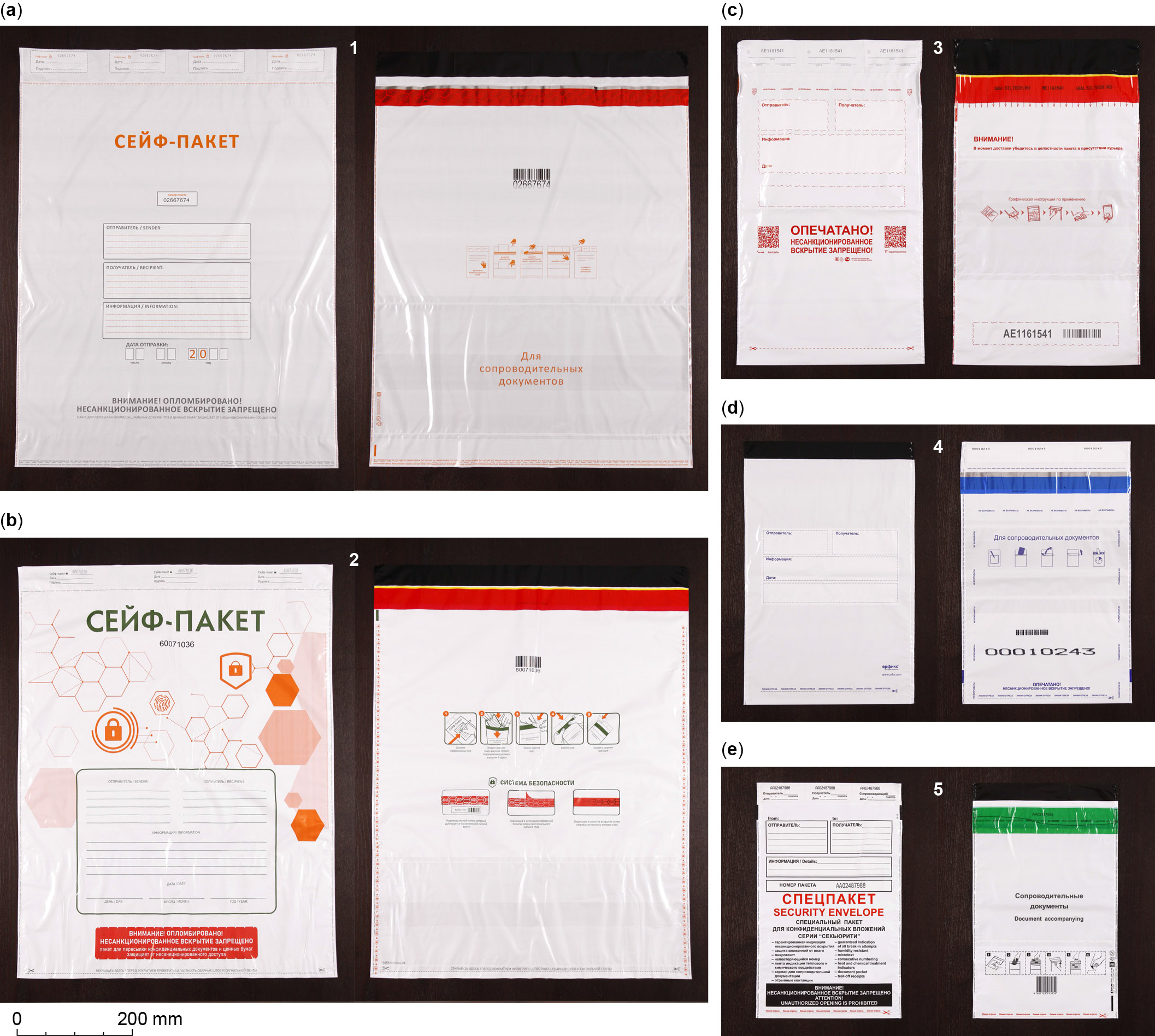

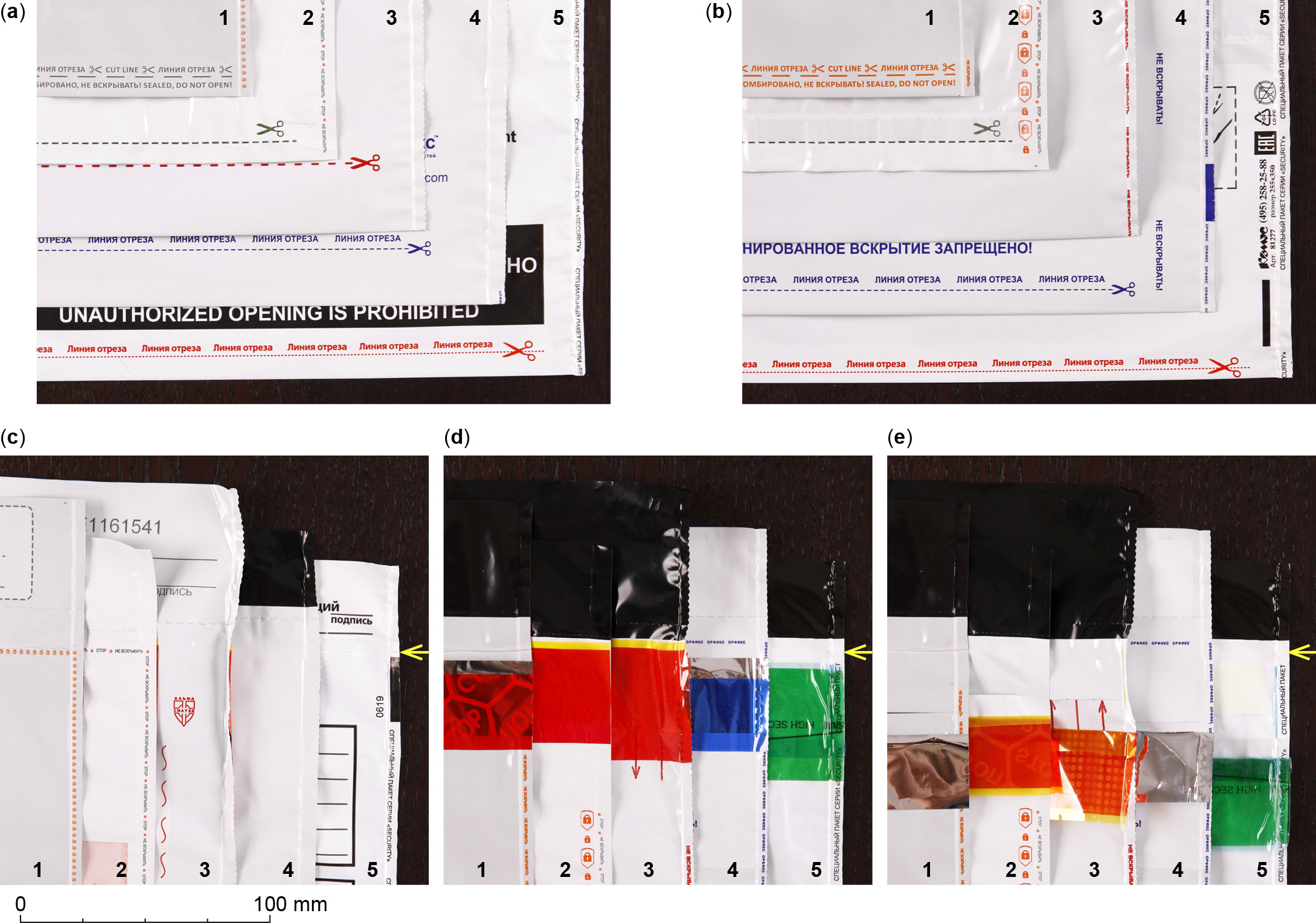

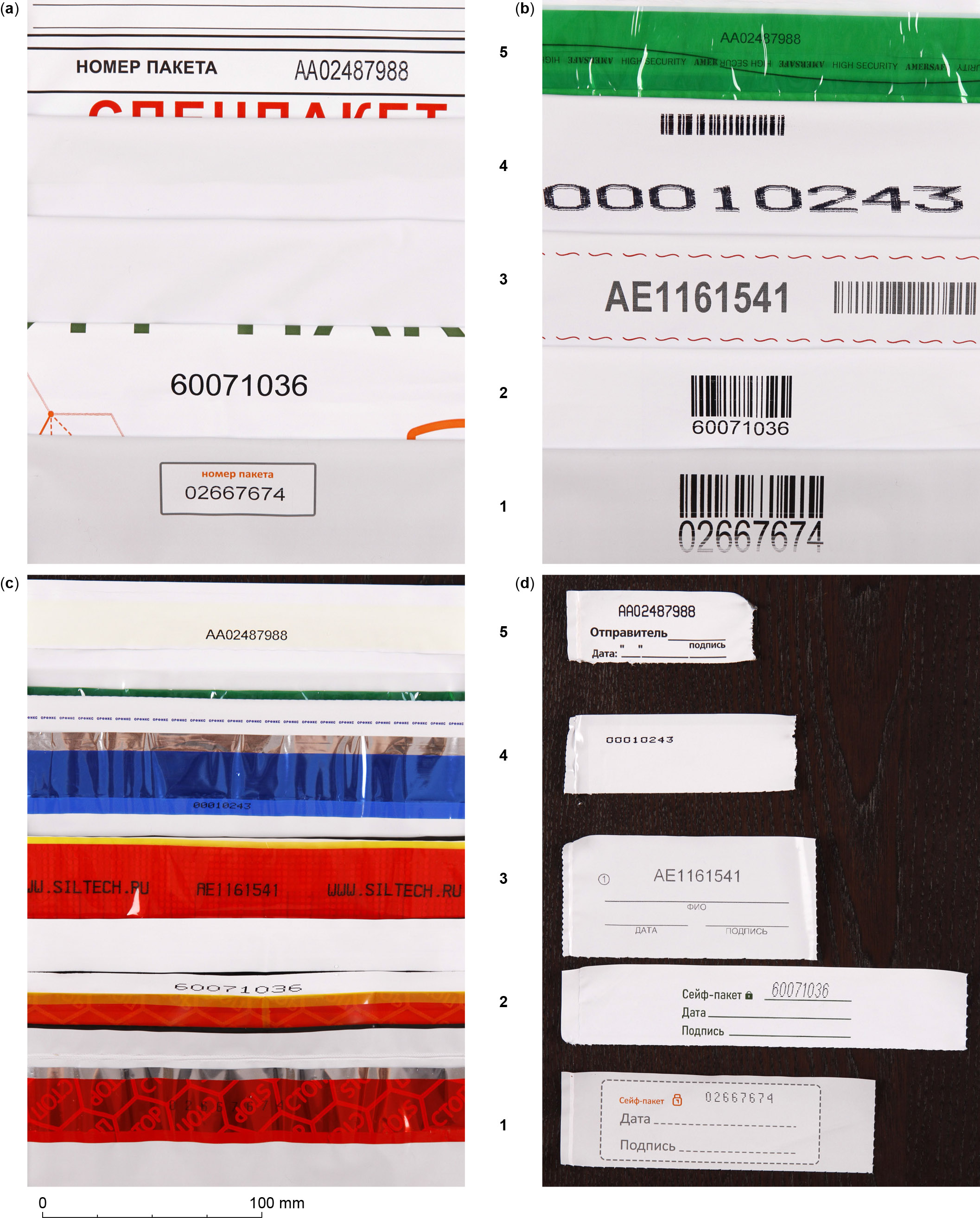

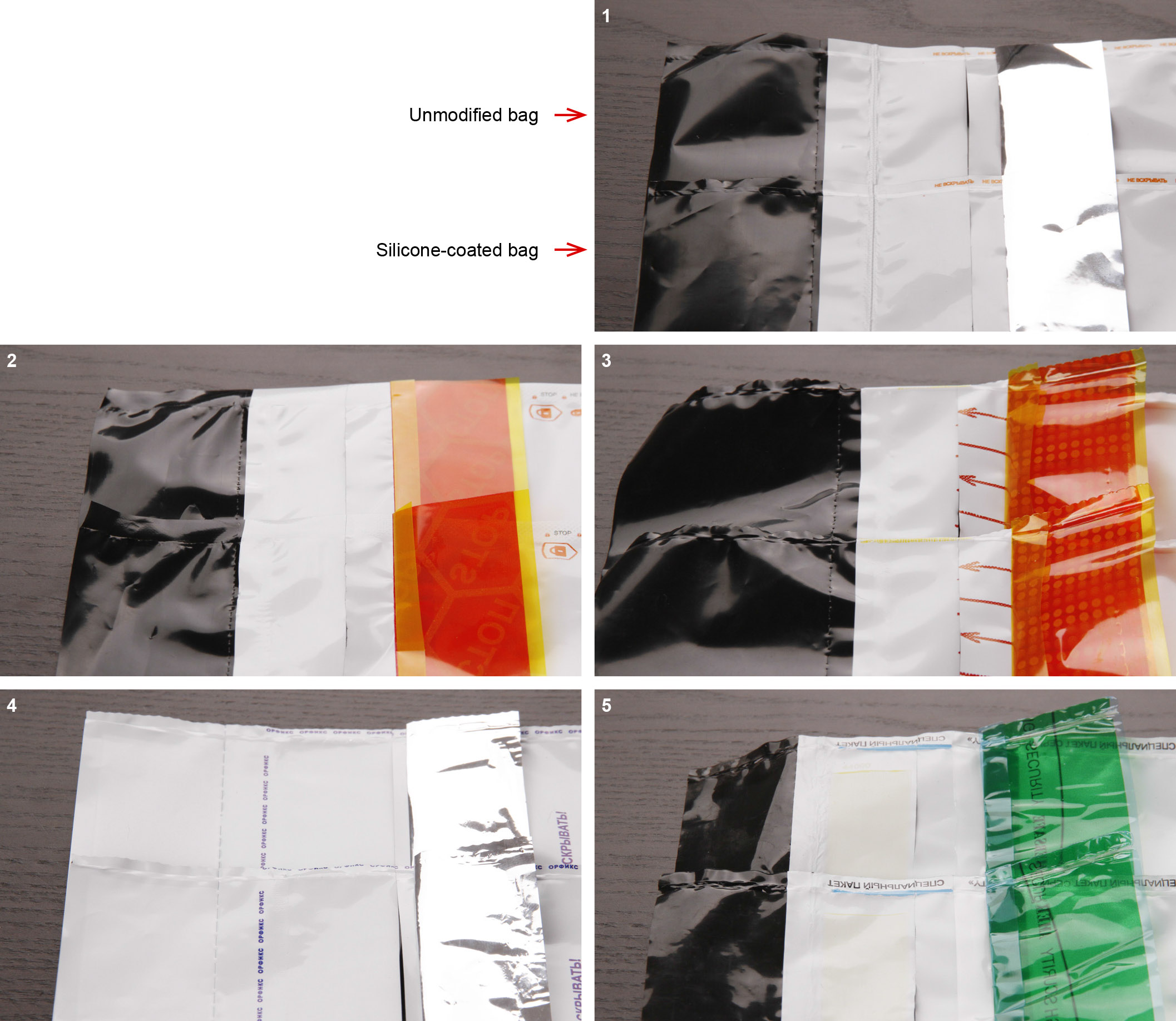

Products from five manufacturers available on the Russian market as of late 2024 were tested (Fig. 1). Two of these were from European brands and three from Russian ones. All of them have virtually identical security features designed to reveal access to the bag’s content. The bag’s bottom edge is formed by a seamless sheet of double-layer polyethylene folded over without a seam. At the side edges, the front and back sides of the bag are joined with heat-sealed seams (Fig. 2). A line of text is printed along the side edges to make an attempt to cut and reseal the edge evident. At the top edge, the front and back sides are also joined with heat-sealed seams (Fig. 2 c–e). The back side near the top is cut across the width of the bag to form an opening (Fig. 2 e). The indicating security tape is preinstalled over the cut, with a few millimeters of the tape’s bottom edge already adhered permanently to the bag below the cut. The rest of the tape’s width remains free, the glue on it being protected from sticking to the bag by a removable liner (Fig. 2 d, e). A unique serial number is printed on the front and back sides of the bag (Fig. 3). It is also printed either on the adhesive side of the tape or beneath the tape, and printed on detachable control stubs (Fig. 3 c, d).

Figure 1. Security bags tested. Front and back side of each is photographed to scale. (a) Bag 1 made by Aceplomb Technology (Russia), https://aceplomb.ru/. (b) Bag 2 trademarked Guardix (made by Imperial-Rus, Russia), https://guardix.ru/. (c) Bag 3 made by Siltech (Russia), https://www.siltech.ru/. (d) Bag 4 made by Orfix (Germany), https://www.orfix.com/. (e) Bag 5 made by Amerplast (Finland), https://amerplast.com/. All the bags were purchased in retail.

Figure 2. Security features at edges of the bags. Each photograph shows five bags. Bottom and side edge are shown from (a) front and (b) back side. A line of small print is placed between the welded seam and the side edge. Top edge is shown from (c) front and (d) back side, the yellow arrow indicating the position of the top welded seam on all five bags. (e) Indicating tape with liner is flipped over, to expose the cut forming the bag opening.

Figure 3. Unique serial number of the bag is printed on (a) front side (except bags 3 and 4), (b) back side (bag 5 has it in the tape sealing area), (c) on or under the tape, and (e) on detachable control stubs.

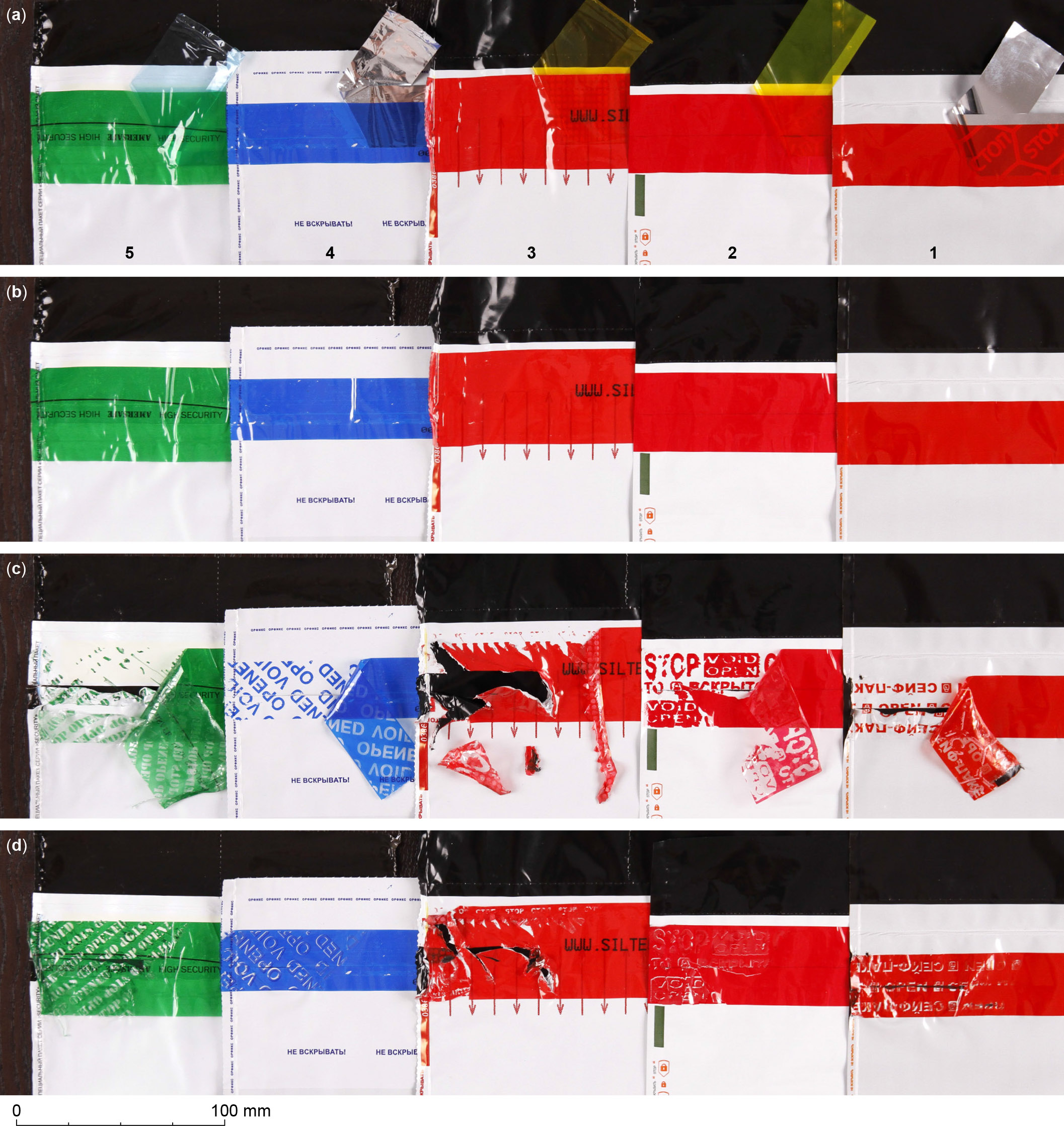

To seal the bag, the liner is removed and the tape is pressed lightly against the back of the bag over its opening (Fig. 4). The tape adheres permanently. Any attempt to remove it tears apart its multi-layer adhesive, revealing embedded lettering. This tampering is apparent and cannot be hidden by an attempt to reinstall the tape back in its original position (Fig. 4 c, d).

Figure 4. Sealing the bag. (a) Liner is removed and tape is pressed over the opening, sealing it permanently. (b) On the sealed bag, the tape shows no features. (c) Any attempt to remove the tape destroys it, leaving visible evidence both on the tape and the bag. (d) Positioning the tape back in its original place does not hide the evidence of its removal.

None of the manufacturers publish a detailed usage and inspection protocol for the bags. The available instructions contain several basic steps, duplicated as illustrations on the back of each bag (Fig. 1). The bags must not be sealed at subzero temperatures. However, once sealed, the tape maintains its indicating properties at any temperature.

Experiment

I attempted to modify these bags to make it possible to unseal and reseal the tape without leaving traces. First, I applied several different liquids and viscous lubricants to bag 1 under its tape, ranging from butter, oils and ointments to machine lubricants and silicone grease with PTFE. I also rubbed the surface of the bag with a paraffin-wax candle. While some of these lubricants prevented immediate adhesion, after a few hours of storage in the sealed state the tape partially adhered and developed traces of damage upon reopening. I concluded that the observer report that alleged the use of an oil-like liquid [21] probably misidentified the surface treatment that was used. Also, all the substances I applied were visible and transferred to fingers upon contact, potentially revealing the tampering attempt.

Next, I attempted to coat the bag under the tape with a drying silicone solution. Unfortunately, the attempt was successful. This treatment produced a dry surface visibly identical to the uncoated one. Yet the tape adhered to it weakly and came off repeatedly without a trace of damage, even after days of storage at room temperature.

First, I prepare the silicone solution. The components for it are available in retail for under €10 (in accordance with the best practices for disclosing physical security vulnerabilities [4], some technical details have been omitted from this article; these will be made available to security professionals upon request). The solution produced a thin transparent coating that matched the semi-matte surface texture of a typical plastic security bag and preserved its visual appearance. To modify an unused bag, the solution was first applied to the inside of the bag under its opening slit with a single brush stroke (Fig. 5 a). The solvent quickly evaporated, leaving behind a thin layer of silicone. The opening could then be padded with paper towels to prevent drops and runs (Fig. 5 b). Masking tape was applied to restrict further coating to a thin strip of outside bag material that the tape contacts when sealing the bag. The solution was applied to this strip with the brush twice, letting the solvent dry between the applications.

Figure 5. Application of silicone coating. (a) The solution is first applied on the inside of the bag under its opening slit, to prevent the tape’s adhesion should it come in contact with that surface during the bag sealing. (b) The solution is then applied on the outside of the bag where the tape comes in contact with it. The ink in serial number of bag 5, printed in the area being coated (denoted by red arrow), is sensitive to the type of solvent.

This coating causes virtually no change to the visual appearance of the bag and is really difficult to notice, especially for a casual observer under typical office lighting conditions. See Fig. 6 for a side-by-side comparison of uncoated and coated bags. It does not smell, either. The person sealing the bag may not realise it has been modified, because the task is to apply the tape and it actually appears to stick to the bag (Fig. 7 a, b). However, adhesion is very weak and the tape can be lifted easily without damage (Figs. 8 and 9). This allows to access the bag contents and reseal it without leaving visible traces (Fig. 7 c). Essentially, the silicone-coated surface mimics properties of a removable liner, which is used with every indicating tape. This hints that this vulnerability is inherent to all indicating tapes and any bag design that uses them.

Figure 6. Side-by-side comparison of the original and silicone-coated bag, under reflective diffuse lighting. The silicone coat’s semi-glossy surface finish closely matches that of the polyethylene material of bags 1–4. Only bag 5 shows a slight difference under these specific lighting conditions, as the originally matte pale-yellow strip printed on it has become more shiny. Spotting this difference requires a careful examination under bright light and specific knowledge what to look for.

Figure 7. Sealing the silicone-coated bag. (a) Liner removes normally and the exposed tape’s glue visually appears to stick to the bag. (b) On the sealed bag, the tape shows no features, as expected. (c) The same bag resealed after opening it and accessing its content. The tape shows no features, as expected. Compare these with Fig. 4 a, b.

Figure 8. Unsealing the silicone-coated bag. The indicating tape is lifted without touching its adhesive, aided by pieces of masking tape temporarily attached to its outer side.

Figure 9. Unsealing the silicone-coated bag. The bag is fully open without any damage to the tamper-indicating tape. Its content can now be accessed. Care should be taken not to let the exposed adhesive touch anything while the bag is open. Handle it by pieces of masking tape temporarily attached.

If there is a risk of further bag inspection or investigation after this action, solvent and paper towels can be used to wash off the silicone before resealing, thereby hiding the traces of backdoor (Fig. 10). In this case, the bag will seal permanently and behave identically to a normal one. In this case, however, the lifted tape has to be reapplied very carefully to reproduce its initial position upon its first contact with the bag surface, as adjusting it would be impossible after that. A silicone-coated transparent spacer temporarily inserted under the tape makes this task easier (Fig. 10 b–d).

Figure 10. Removing the backdoor, demonstrated on bag 1. (a) The silicone coat is softened and washed off with the solvent. (b) A silicone-coated transparent plastic spacer (denoted by yellow arrow) is inserted in the opening before lowering the tamper-indicating tape over it. The tape is then aligned along its length to the final position. (c, d) Once the tape position is verified, the spacer is gradually withdrawn and the tape pressed against the bag. (e) The bag is sealed permanently. (f) and (g) After sealing, the tape shows its normal tamper-indicating behaviour upon an attempt of unsealing.

Let us briefly consider what a perpetrator may do in case of a mistake that damages the tape during unauthorised access. First, preliminary practice using extra samples of the bag reduces the risk of such errors. If the damage to the tape is minor in a small spot, a permanent colour marker may reasonably mask point damage. Should the tape be damaged beyond repair, the following options are available. For those bags that do not have the serial number printed on the tape (such as bags 2, 4, and 5), it may be peeled off fully, its adhesive residue washed off with the solvent, and replaced with fresh tape cut from an unused bag [16]. This reduces the tape width, but few people would notice that. To avoid tears in the bag while removing the tape, it may be deep-cooled briefly with liquid from an inverted dust-blower can (needed for bag 5). The serial number can be reprinted if necessary, using a handheld inkjet printer (needed for bag 2). Alternatively, an imitation made from packing tape of a similar colour may be installed [16]. The number can be reproduced with the handheld inkjet printer as well.

Discussion

In most cases of using security bags, multiple individuals have access to the bag before it is sealed. Opportunities exist for installing the backdoor or swapping the bags for ones with the backdoor in the procurement and delivery chain, during storage, and during the first sealing. Detecting this backdoor requires training and hands-on inspection procedures both prior to the sealing and during opening, which most users do not implement.

In many cases of using the bag, the individual performing the sealing or unsealing might be interested in compromising the bag contents. Among these uses, elections present a challenging case. During elections, every party involved fundamentally mistrusts everyone else, yet everyone should be able to verify the security of the bag with little or no advance training. I will therefore discuss this case in detail using Russian multi-day elections conducted since 2020 as a case study [19].

At the end of every voting day except the last day, the cast ballots are sealed inside the bag and stored without supervision until the end of the last day, when the vote tallying takes place. Election officials receive no training in the use of security bags. Regulations require only visual inspection “for signs of damage indicating compromised integrity” and verification of the bag number (Federal Law No. 67-FZ “On basic guarantees of electoral rights and the right of citizens of the Russian Federation to participate in a referendum” delegates the procedure to the Central Election Commission to set detailed procedures for multi-day voting (Article 63.1 Clause 9); currently, these are established by CEC Resolution No. 86/718-8 [17]). There are no requirements on the quality and source of the bags and no provisions for their post-mortem examination (inspection of used bags after opening them). There are numerous reports of criminal tampering with the bags, incorrect sealing, access by election officials and other people to their storage places at night time, and commissions preventing the observers from inspecting the bags. There are over 40 of such complaints nationwide only from the limited-scale September 2024 election campaign [3; 11; 16; 18; 20; 21], which is about 10% of all the complaints reported during the voting [11]. I suspect a backdoor method similar to that presented here has already been used to replace the ballots in storage [3; 18; 21]. I would like to point out that, historically, bags made by Aceplomb Technology (such as bag 1) have been used during elections most often [11], however bag 2 and the other brands have also sometimes been used.

While abolishing multi-day voting may seem like an easy solution, in the case of single-day voting, the law requires early voting to be made available. The ballot storage issue thus remains. Early-voting ballots are stored in regular paper envelopes, which have also shown traces of tampering in documented cases [13; 15].

While it is known that tamper-indicating seals are unsuitable in general for securing modern elections [1; 5; 12; 16; 22], steps can be taken to require proper training of election officials and implementation of the use protocol [6; 9; 10; 14]. In my opinion, the current regulations [17] are inadequate and must be revised to reflect the reality of vulnerabilities in ballot storage. A module on handling and inspecting the bags (with examples of tampering) should be added to the mandatory online training program for election officials. Within each individual polling station, bags of only one model should be used. A training exercise using a sample bag should be conducted at every polling station on the first voting day before the actual use of the bags for ballot storage. An additional unused bag sample should be provided to the observers present at the station. The procedures should be amended to allow hands-on inspection by everyone present at the polling station, including the observers. The particular backdoor shown in this paper is detectable by testing the bag’s adhesion to a piece of masking tape — the procedures should authorise each observer and commission member to do that. Sufficient time (not less than 3 min per bag) should be allotted to bag inspection, and close-up photography should be allowed. The polling station should be equipped with a desktop lamp for the inspection under bright light. Handwritten signatures should be allowed over the indicating tape (at present, they are only allowed outside the tape [17]). Before the bag is opened at the vote tallying, it needs to be compared side-by-side with an unused bag sample to spot any discrepancies [9]. All individuals present at the polling station should be allowed to examine the used bags (after the ballots are extracted from them) hands-on, including turning them inside out to inspect the inner surfaces and seams, and removing their security tapes. Should evidence of tampering with the bag be discovered, the precinct commission should have no choice but to declare the ballots extracted from it invalid. The used bags and their parts detached must be stored, together with other precinct documents, for one year to allow for their re-inspection [10; 14].

In addition to the rules for the polling stations, provisions need to be made to prevent the manufacture of bags and tamper-indicating seals with duplicate numbers, which takes place at present [12; 16]. Perhaps certification of certain bag models by the Central Election Commission or their centralised procurement will preclude such quality issues.

Furthermore, round-the-clock video surveillance footage from polling stations is valuable for checking the integrity of ballot storage. While the recordings used to be broadcast on the Internet before 2020, at present they are de facto impossible to obtain. Public access to these recordings should be restored.

Conclusion

I have described a simple method for installing a backdoor in a security bag. The analysis covers its use in Russian multi-day elections and highlights the need for significant changes in the procedures. These findings are also applicable for other security bag use cases.

I acknowledge unknown individuals who invented and applied this tampering method before me [3; 18; 21] but hesitated to publish it. This paper was shared with the bag manufacturers and the Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation prior to its publication. The latter responded that “information regarding the alleged violations... was checked and not confirmed” and that “speculation about possible violations in the absence of facts cannot form the basis for... complicating election procedures”.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Details of materials and methods are available from the author on reasonable request.

Received 10.04.2025, revision received 08.05.2025.

References

- Appel A.W. Security seals on voting machines: a case study. – ACM Transactions on Information and System Security. 2011. V. 14. P. 18. DOI: 10.1145/2019599.2019603.

- DoD training course for effective seal use. Special publication SP-2086-SHR. Port Hueneme, California: Naval facilities engineering service center. 2000. 87 p. URL: http://www.vad1.com/e/2000.SP-2086-SHR.pdf (accessed 11.05.2025). - http://www.vad1.com/e/2000.SP-2086-SHR.pdf

- Elektoralnaya mantra v Mytishchah: kak pod vidom vyborov proveli naznachennyh kandidatov [Electoral Mantra in Mytishchi: How Pre-Chosen Candidates Were Installed Under the Guise of Elections]. – Govoryat Mytishi, 20.10.2024. URL: https://vk.com/@mspeaks-elektoralnaya-mantra-v-mytischah (accessed 31.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://vk.com/@mspeaks-elektoralnaya-mantra-v-mytischah

- Johnston R.G. A model how to disclose physical security vulnerabilities. – Journal of Physical Security. 2009. V. 3. No. 1. P. 17–35. URL: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/xyvxui4gbut2jlzg6du79/AFtpZHXpWaE_JaqmT16mxlM/Journal%20of%20Physical%20Security?rlkey=byt98rngpxfqgfwvfi80iq1kb (accessed 08.05.2025). - https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/xyvxui4gbut2jlzg6du79/AFtpZHXpWaE_JaqmT16mxlM/Journal%20of%20Physical%20Security?rlkey=byt98rngpxfqgfwvfi80iq1kb

- Johnston R.G. A vulnerability assessment of “indelible” voter’s ink. – Journal of Physical Security. 2017. V. 10. No. 1. P. 30–56. URL: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/xyvxui4gbut2jlzg6du79/AFtpZHXpWaE_JaqmT16mxlM/Journal%20of%20Physical%20Security?rlkey=byt98rngpxfqgfwvfi80iq1kb (accessed 08.05.2025). - https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/xyvxui4gbut2jlzg6du79/AFtpZHXpWaE_JaqmT16mxlM/Journal%20of%20Physical%20Security?rlkey=byt98rngpxfqgfwvfi80iq1kb

- Johnston R.G. Poor practice using pressure-sensitive adhesive label seals. – Journal of Physical Security. 2019. V. 12. No. 2. P. 18–28. URL: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/xyvxui4gbut2jlzg6du79/AFtpZHXpWaE_JaqmT16mxlM/Journal%20of%20Physical%20Security?rlkey=byt98rngpxfqgfwvfi80iq1kb (accessed 08.05.2025). - https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/xyvxui4gbut2jlzg6du79/AFtpZHXpWaE_JaqmT16mxlM/Journal%20of%20Physical%20Security?rlkey=byt98rngpxfqgfwvfi80iq1kb

- Johnston R.G. Tamper-indicating seals. – American Scientist. 2006. V. 94, P. 515–523. DOI: 10.1511/2006.62.515.

- Johnston R.G. Tamper-indicating seals for nuclear disarmament and hazardous waste management. – Science and Global Security. 2001. V. 9. P. 93–112. DOI: 10.1080/08929880108426490.

- Johnston R.G., Warner J.S. How to choose and use seals. – Army Sustainment. 2012. V. 44. No. 4. P. 54–58. URL: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA566079.pdf (accessed 08.05.2025). - https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA566079.pdf

- Johnston R.G., Warner J.S. Suggestions for better election security. – Journal of Physical Security. 2011. V. 5. No. 1. P. 73–77. URL: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/xyvxui4gbut2jlzg6du79/AFtpZHXpWaE_JaqmT16mxlM/Journal%20of%20Physical%20Security?rlkey=byt98rngpxfqgfwvfi80iq1kb (accessed 08.05.2025). - https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/xyvxui4gbut2jlzg6du79/AFtpZHXpWaE_JaqmT16mxlM/Journal%20of%20Physical%20Security?rlkey=byt98rngpxfqgfwvfi80iq1kb

- Karta narusheniy [The map of electoral violations]. URL: https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/ (accessed 07.01.2025). (In Russ.) - https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/

- Leningradskaya oblast, Kudrovo: dlya opechatyvaniya seifa s izbiratelnoi dokumentatsiyei ispolzuyutsya seif-nakleiki s odinakovymi nomerami [Kudrovo, Leningrad Oblast: Tamper-Indicating Seals With Identical Numbers Are Used on the Safe]. – Karta narusheniy, 08.09.2024. URL: https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/messages/84888 (accessed 07.01.2025). (In Russ.) - https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/messages/84888

- Leningradskaya oblast, pos. imeni Morozova: vse uchastkovye izbiratelnye komissii v posyolke prinyali resheniya o priznanii nedeistvitelnymi bolshogo kolichestva byulletenej dosrochnogo golosovaniya [Morozov Township, Leningrad Oblast: All Precincts in the Township Invalidate a Large Number of Early-Voting Ballots]. – Karta narusheniy, 14.02.2016. URL: https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/messages/31467 (accessed 07.05.2025). (In Russ.) - https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/messages/31467

- Melanich E.V. Pechati: sem tysyach let. Profilaktika pravonarusheniy [Seven Thousand Years of Seals. Crime Prevention]. 2021. Moscow: Siltech, 2021. 208 p. (In Russ.)

- Podivilov M. Sud v Ljubercah rassmotrit moj isk k predsedatel'nice uchastka [A court in Lyubertsy will hear my case against the precinct chair]. – Golos Movement Website (included in the register of foreign agents), 28.11.2022. URL: https://golosinfo.org/articles/146295 (accessed 07.05.2025). (In Russ.) - https://golosinfo.org/articles/146295

- Podlazov A., Makarov V. Dual approach to proving electoral fraud via statistics and forensics. – arXiv:2412.04535 [stat.AP]. 2024. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.04535 (accessed 08.05.2024). - https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.04535

- Polozheniye ob osobennostyakh golosovaniya, ustanovleniya itogov golosovaniya v sluchaye prinyatiya resheniya o provedenii golosovaniya na vyborakh, referendumakh v techeniye neskolkikh dnei podryad [Resolution of Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation No. 86/718-8 from 8 Jun 2022 “On the specifics of voting over several consecutive days”] (with amendments effective on 10.07.2024). URL: https://www.nablawiki.ru/index.php/НПА:Постановление_ЦИК_России_от_08.06.2022_№_86/718-8:Приложение (accessed 07.01.2025). (In Russ.) - https://www.nablawiki.ru/index.php/НПА:Постановление_ЦИК_России_от_08.06.2022_№_86/718-8:Приложение

- Sankt-Peterburg, Kalininsky rayon: pri vskrytii seif-paketa vyjasnilos, chto on “mnogorazovyj”. Krasnaja lenta legko otkleivalas' i obratno zakleivalas' bez kakih-libo sledov [Kalininsky District of St. Petersburg: When opened at vote tallying, the security bag was found to be “resealable”; the red tape could be easily peeled off and resealed without leaving any traces]. – Karta narusheniy, 09.09.2024. URL: https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/messages/85073 (accessed 07.01.2025). (In Russ.) - https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/messages/85073

- Skryabin V. Istoriya mnogodnevnogo golosovaniya na vyborakh prezidenta RF [The History of Multi-Day Voting at Presidential Elections in Russia]. – TASS, 13.03.2024. URL: https://tass.ru/info/18683391 (accessed 31.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://tass.ru/info/18683391

- V Korolyove vskryli i zapechatali seif-paket (s pomoshchyu zapaishhika paketov) [Korolyov, Moscow Oblast: Security bag opened and resealed with a heat-sealing machine]. – Nablyudateli na vyborah v MO, 12.09.2024. URL: https://t.me/nabludatMO/850 (accessed 31.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://t.me/nabludatMO/850

- V podmoskovnykh Bronnitsakh seif-paket smazali maslom: tak yego mozhno raspechatat bez sleda [Bronnitsy, Moscow Oblast: A security bag smeared with oil allows traceless unsealing]. – Karta narusheniy, 07.09.2024. URL: https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/messages/84636 (accessed 31.10.2024). (In Russ.) - https://www.kartanarusheniy.org/messages/84636

- Wolchok S., Wustrow E., Halderman J.A., Prasad H.K., Kankipati A., Sakhamuri S.K., Yagati V., Gonggrijp R. Security analysis of India’s electronic voting machines. – Proceedings of 17th ACM conference on Computer and communications security. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. 2010. P. 1–14. DOI: 10.1145/1866307.1866309.