Institutionalization of Russia’s Party System (Based on Scott Mainwaring’s Indicators)

Abstract

Political scientists use a range of parameters and indicators to study the institutionalization of party systems. One such set of indicators was developed by Scott Mainwaring. While analyzing party system institutionalization in Latin American countries, he argues that his criteria are universal and applicable to a wide variety of states, including those with both highly stable and extremely volatile party systems. This article applies Mainwaring’s parameters for assessing party system institutionalization to the case of Russia. Their calculation relies on formulas of electoral volatility, standardized scores, and equations constructed by Mainwaring himself. By following the substantive rules and mathematical procedures used by Scott Mainwaring, this study identifies specific indicators that reflect the level of institutionalization of the Russian party system. At the same time, these indicators are placed within the overall dataset for the Latin American countries and the United States and compared to those of these states. This approach allows for a more accurate assessment of whether Russia’s party system is weakly or highly institutionalized in comparison with the systems of several other countries. The empirical results obtained through Mainwaring’s methodology place Russia alongside the moderately institutionalized party systems of Latin American countries. Ultimately, the findings confirm the conclusions of many Russian scholars that Russia’s party system has not yet become an entrenched institution and continues to exhibit instability. At the same time, the results support the assumption that Mainwaring’s parameters have significant potential and may, in the future, become part of a unified set of criteria for assessing the degree of institutionalization of party systems in different countries.

Introduction

Party systems constitute an integral component of the political order in the majority of modern countries. They exist in virtually all countries of the world, with the exception of certain monarchies in the Middle East and some Pacific island countries. Party systems may be either static and stable or dynamic and changeable formations, and over time they may become more or less institutionalized. "In politics, institutionalization means that political actors have clear and stable expectations about the behavior of other actors... An institutionalized party system, then, is one in which actors develop expectations and behavior based on the premise that the fundamental contours and rules of party competition and behavior will prevail into the foreseeable future. In an institutionalized party system, there is stability in who the main parties are and how they behave" [20: 206]. The strength of party systems vary from one state to another, ranging from highly fragile to markedly stable configurations.

To assess these degrees of institutionalization, political scientists rely on a broad set of criteria. Researchers either draw upon indicators proposed by earlier scholars or devise new ones independently. As a result, the number of such indicators is constantly increasing, giving rise to a twofold situation. On the one hand, a wide range of parameters emerges, from which one can assemble a compact "toolkit" optimally suited to a specific study of party system institutionalization in a given country (or group of countries). On the other hand, researchers may employ indicators that in fact lack cause-and-effect connections with one another and ultimately prove incompatible: "There is a risk that a researcher may mix heterogeneous, incongruent parameters of party institutionalization, which in turn may reduce the reliability of scientific conclusions" [15]. This problem is exacerbated when such disparate indicators are applied in comparative research, where the objects of analysis are party systems that differ markedly across countries. For this reason, when examining the evolution of the party system as an institution, analytical methods and techniques should rely on criteria that are consistent with one another and mutually complimentary.

In addition, one should not overload the study with an excessive number of indicators; their composition must be balanced so as to maintain a coherent analytical framework. When attempting to account for all the numerous dimensions of party systems, one may, first, end up analyzing the same features several times, which would unnecessarily expand the amount of work. Second, there is a risk of using facts or data that have not previously been thoroughly investigated and may therefore prove irrelevant or corrupted [10: 8]. To avoid these pitfalls, it is advisable to rely on a limited set of congruent and internally coherent parameters.

Such a set of indicators for assessing the institutionalization of a country’s party system was proposed by Scott Mainwaring, Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame (USA), whose research interests include political parties, party systems, and the democratic transformation of Latin American countries. In one of his recent works [18], he employs thirteen indicators to measure the level of party system institutionalization (PSI) in Latin American countries, several of which he developed himself. In his opinion, these indicators are "straightforward, informative, easy to operationalize, and comparable across cases and over time. They can be used for analyses of party system change and stability in all regions of the world" [18: 34]. Thus, in Mainwaring’s view, his parameters possess universal features and can be applied to the analysis of both highly stable and weak party systems across a wide range of countries.

The party system of contemporary Russia has been developing for more than thirty years. Over this period, it has undergone several stages of development, each marked by factors that either accelerated or hindered the process of institutionalization [7; 13; 22; 24]. The transformation and reconfiguration of the party landscape continue to this day.

This article aims to determine the level of institutionalization of Russia’s contemporary party system on the basis of specific indicators developed by Scott Mainwaring. The first task of the study is to use empirical calculations to show precisely to what extent the Russian party system constitutes a stable or volatile institution in comparison with the systems of several other states.

The second task is to establish whether Mainwaring’s criteria indeed possess the analytical potential to measure PSI levels across different countries and time periods, as the scholar himself asserts. A positive or negative answer can be obtained by comparing the mathematical results calculated in the present study with the earlier findings of other political scientists specializing in the Russian party system. Such a comparison (at least in the case of Russia) will either confirm or refute Mainwaring’s claim that his indicators are promising tools for assessing PSI levels across a wide range of states.

Materials and methods

Although this article examines only one country – the Russian Federation – it nevertheless constitutes a comparative study. The quantitative indicators describing Russia’s party system are placed within an existing general dataset, and Russia’s PSI values are compared with those of Latin American countries and several other states.

There are, of course, substantial differences between Russia and the Ibero-American states. These include the political and cultural conditions shaping the emergence of contemporary institutional designs; the form of republican governance; the role of the military and bureaucratic elites in constructing the political system; the particularities of major economic reforms; the characteristics of party systems (including whether parties are allowed or forbidden to form coalitions prior to elections); patterns of social stratification and group interests as well as other differences.

Despite these differences, the nations also share certain common features. Chief among them is the dominant role of the state as the initiator of transformations that ultimately penetrate all spheres of society and give rise to national institutions. As Tatyana Vorozheikina notes: "Despite the civilizational, cultural, and historical differences – linked above all to the imperial past (and its 'phantom' and quite tangible pains in the present) – Russia shares with the Latin American countries a common pattern of societal development, namely its state-centered matrix. I use this term to characterize a type of development in which the state (the authorities) plays a central role in shaping (structuring) economic, political, and social relations" [31: 6]. Pyotr Yakovlev also concurs that a "state-centered" model is typical of both Russia and the Latin American states. He argues that, unlike the classical scheme in which economic relations constitute the foundation upon which all other social relations are subsequently built, Russia and Latin America went through the opposite, inverted process: the state functioned as the leading force that consolidated social groups and ensured economic growth [33: 80].

The state’s pivotal role likewise shapes the characteristics of the party system. A phenomenon shared by Russia and the Latin American countries is the "party of power." This is "a party-type or quasi-party-type organization created by the elite for the purpose of participating in elections" [6: 7]. Yurii Korgunyuk maintains, in particular, that political competition has been significantly restricted in the Latin American states in the recent past and continues to be limited in several CIS republics today (including Russia). To secure their political positions, elites construct a "party of power" and employ additional administrative instruments [12: 51].

If the indicators developed by Scott Mainwaring for analyzing PSI are indeed comprehensive and analytically productive, this would imply that the overall dataset should include all states whose party systems demonstrate varying degrees of institutionalization, including those that have only recently emerged or are continually changing, as well as the party systems of states from different regions of the world and from other historical periods. For this reason, this article places Russia in the general list of Latin American countries and the United States and conducts a comparative analysis. Such a comparison becomes even more appropriate given the presence of similar formative conditions and contemporary attributes characteristic of both the Russian and Latin American party systems. Moreover, Mainwaring himself utilized a comparative approach with respect to the United States: confident in the reliability of his indicators and regarding the country as a useful benchmark for comparison, he incorporated it into the pool of Ibero-American states, even though the U.S. party system developed under its own unique conditions. A comparison between Russia and the countries of the New World reveals the differences in the institutionalization levels of their respective party systems and thereby indicates the extent to which Russia’s party system is more stable or more volatile than others.

In his book, Scott Mainwaring analyzes party system institutionalization in eighteen Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, El Salvador, Uruguay, and Venezuela), as well as in the United States, over the period from 1990 to 2015. For this purpose, he uses thirteen indicators grouped into three blocks: the first two contain six indicators each, while the third consists of a single, eponymous indicator.

The indicators of the first block, "Stability in the membership of the party system participants," are as follows:

"Vote share of new-party candidates in presidential elections,"

"Vote share of new parties in lower chamber elections,"

"Stable participation of significant contenders, election-to-election (presidential),"

"Stable participation of significant contenders, election-to-election (lower chamber),"

"Medium term stability of significant contenders, from one election to the next, presidential elections,"

"Medium term stability of significant parties, from one election to the next, lower chamber elections."

The indicators of the second block, "Stability of inter-party competition," are as follows:

"Mean electoral volatility in presidential elections,"

"Mean electoral volatility in lower chamber elections,"

"Cumulative electoral volatility in presidential elections,"

"Cumulative electoral volatility in lower chamber elections,"

"Vote share of old-party candidates in the recent presidential election,"

"Vote share of old-party candidates in the recent lower chamber election."

The final, third block (as well as the thirteenth parameter) is titled "Stability in party linkage with society: Change in parties’ ideological positions."

Drawing on the accumulated data, Mainwaring also examines the extent to which Latin American countries follow path dependence (are dependent on the trajectory of their prior development): how far the aforementioned indicators identified in the past influence those obtained in the present, and whether they are capable of shaping corresponding indicators in the future. In addition, he calculates the degree to which several independent variables (a country’s GDP growth, GDP per capita, inflation rate, effective number of parties, constituency size, the year in which democracy was established, age of democracy, form of government) affect the dependent variables (extra-system and average electoral volatility). Such integrative calculations with respect to Russia fall outside the scope of this article, but they may well serve as a subject for future research.

To develop universal PSI criteria, Scott Mainwaring formulates a set of strict rules, which he explains separately and in detail [19; 28]. For example, if several parties or organizations that participated in the previous legislative elections t merge into a single new party that contests the current elections t+1, the resulting merged party is treated as the successor of the party that achieved the highest vote share in elections t. The parties that received smaller vote shares in elections t are considered disappeared in elections t+1. In Powell and Tucker’s terminology, discussed below, these are old parties that "leave" the system, except in cases where such parties later re-emerge as separate actors and re-enter electoral competition.

Thus, for example, in this article Russia's Union of Right Forces is treated, in accordance with Mainwaring’s rules, as the successor to the Choice of Russia electoral bloc. This is because the merger of several parties into a single organization followed a chain in which the party achieving the highest vote share in the last electoral cycle became the basis for consolidation with its future allies in the subsequent cycle. Consequently, Choice of Russia transformed into Democratic Choice of Russia, which served as the nucleus around which the Union of Right Forces was formed.

The same principle applies, among other cases, to the Party of Growth. Civilian Power is considered as its predecessor, since in the most recent State Duma election in which Civilian Power, the Union of Right Forces, and the Democratic Party of Russia all participated, it received the highest vote share; it therefore became the ancestral organization that, after merging with the latter two in 2008, gave rise to Right Cause, which was later reorganized as the Party of Growth. Despite the fact that the Party of Growth was incorporated into New People at a joint party congress in April 2024, New People is classified as an independent party (and the Party of Growth as disappeared). This is because, in the most recent federal elections in which both organizations competed (the 2021 State Duma elections) New People received a higher vote share than the Party of Growth.

Under the same approach, A Just Russia – For Truth is considered the successor to the Congress of Russian Communities movement. The Congress first participated in federal elections in 1995, submitting its own list of candidates for the State Duma. The following year, a Congress-backed candidate (Alexander Lebed) ran quite successfully in the presidential election. Prior to the next parliamentary elections (1999), the organization joined an electoral bloc called "Congress of Russian Communities and Yuri Boldyrev’s Movement". On the eve of the 2003 State Duma election, a significant consolidation took place: three official parties (the Party of Russian Regions, the People’s Will Party of National Revival, and the Socialist United Party of Russia) and two movements (the Congress of Russian Communities and For a Decent Life) merged into the electoral bloc "Rodina – People’s Patriotic Union". Although only the three parties were formally listed as the founders of the bloc, this article treats Rodina as the successor to the Congress of Russian Communities, since among all five constituent organizations it was the Congress that possessed the strongest and most substantial record of participation in federal elections.

Subsequently, in 2007, Rodina became the principal (and formally the sole) founding party of "A Just Russia: Rodina/Pensioners/Life". This was because in the preceding 2003 State Duma election it obtained a higher result than the other groupings that were incorporated into A Just Russia — namely, the bloc "Russian Party of Pensioners and Party of Social Justice" and the bloc "Party of Russia’s Rebirth – Russian Party of Life". "AJR: Rodina/Pensioners/Life" subsequently evolved into A Just Russia (in the federal elections of 2011, 2012, and 2016), and later into A Just Russia – For Truth (2021). Some researchers also argue that, in terms of its ideological and programmatic positions, "Mironov’s party has definitively distanced itself from the social-democratic discourse that constituted its ideological core from the moment of its founding, in favor of 'statist' and 'imperial' concepts" [9: 71].

The same method of identifying predecessors and successors is applied to other parties that took part in federal elections:

· The Unity bloc (which competed in the 1999 State Duma election and is also treated in this article as the nominating subject for Vladimir Putin in the 2000 presidential election, as discussed below) became the foundation of United Russia, which took part in all subsequent federal elections;

· The Zhirinovsky Bloc (1999) temporarily and out of necessity replaced the LDPR (which took part in every other election);

· The "Yavlinsky – Boldyrev – Lukin" bloc (1993) was transformed into Yabloko (ran in all subsequent elections);

· The Constructive-Ecological Movement of Russia "Kedr" (1993) evolved into the Environmental Party of Russia "Kedr" (1995), and later into the Russian Ecological Party "The Greens" (2003, 2016, 2021);

· The Party of Pensioners (1999) evolved into the Russian Party of Pensioners, which formed a bloc with the Party of Social Justice in 2003 (in 2007 the Party of Social Justice is treated as the successor of this bloc, but subsequently disappears), then into the Russian Party of Pensioners for Justice (2016), and later into the Russian Party of Pensioners for Social Justice (2021);

· Republican Party of the Russian Federation, which constituted the core of the "Pamfilova – Gurov – Vladimir Lysenko" bloc (1995), became part of the "New Course – Automotive Russia" bloc (2003), and later People’s Freedom Party (2016);

· "Communists – Working Russia – For the Soviet Union" bloc (1995) transformed into the "Communists, Working People of Russia – For the Soviet Union" bloc (1999);

· Party of Workers’ Self-Government (1995, 1996) served as the foundation for the "General Andrei Nikolaev and Academician Svyatoslav Fedorov Bloc" (1999);

· Russian All-People’s Union was one of the founders of the "Power to the People!" electoral bloc (1995, 1996) and subsequently competed independently (1999, 2018).

When several parties merge into a single organization, those that participated in the merger but received a lower vote share than the principal founding party in the previous federal election leave the political system. This category includes organizations with an electoral history in federal elections, such as: the Union of Right Forces and the Democratic Party of Russia (merged into Right Cause); Fatherland – All Russia and the Agrarian Party of Russia (joined United Russia); Spiritual Heritage, the Socialist United Party of Russia, the Russian All-People’s Union, the Party of Pensioners, the Party of Social Justice, the Russian Party of Life, and Patriots of Russia (all became part of A Just Russia – For Truth).

However, after leaving the political arena, some organizations later re-emerge and take part in elections again as independent actors. In Mainwaring’s terminology, such parties are treated as independent actors, yet they are considered old; accordingly, they contribute to within-system rather than extra-system volatility. These parties include: Rodina (which broke away from A Just Russia and competed independently in the 2016 and 2021 State Duma elections); the Russian Party of Pensioners for Social Justice (which also split from A Just Russia and took part in the 2016 and 2021 Duma elections); the Russian All-People’s Union (which left Rodina, was able to nominate its own candidate in the 2018 presidential election, but was dissolved in 2025); and Civilian Power (which re-emerged after the creation of Right Cause, participated in the 2016 Duma election, but was likewise dissolved in 2025).

Proceeding from the above, the parties participating in elections to the State Duma can be categorized as old, new, and disappeared (Table 1).

Table 1. Categorization of parties in elections to the lower house of parliament

| Year | Old parties participating in the elections | New parties participating in the elections | Old parties absent in these elections but present in previous and at least one subsequent election | Disappeared parties previously participating | |

| 1993 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1995 | 8 (CPRF; LDPR; Yabloko Association; “Democratic Choice of Russia – United Democrats” bloc; Agrarian Party of Russia; Party of Russian Unity and Accord; Environmental Party of Russia “Kedr”; “Women of Russia” movement) | 35 | 1 (Democratic Party of Russia) | 4 (“Civic Union for the Sake of Stability, Justice, and Progress” bloc; Russian Movement for Democratic Reforms; “Dignity and Mercy” association; “Russia’s Future – New Names” association) | |

| 1999 | 11 (CPRF; "Zhirinovsky Bloc"; Yabloko Association; All-Russian Public Movement "Our Home – Russia"; "Union of Right Forces" bloc; "Congress of Russian Communities and Yuri Boldyrev’s Movement" bloc; Russian All-People’s Union; "Women of Russia" movement; "Communists and Working People of Russia – For the Soviet Union" bloc; "Social Democrats" bloc; "Bloc of General Andrei Nikolayev and Academician Svyatoslav Fedorov") | 15 | 3 (Agrarian Party of Russia; Environmental Party of Russia “Kedr”; Republican Party of Russia) | 29 | |

| 2003 | 12 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR; Yabloko; Union of Right Forces; Democratic Party of Russia; Agrarian Party of Russia; “Rodina” bloc; “Russian Party of Pensioners and Party of Social Justice” bloc; REP The Greens; “New Course – Automotive Russia” bloc; Party of Peace and Unity) | 11 | 0 | 18 | |

| 2007 | 9 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR; Yabloko; Union of Right Forces; Democratic Party of Russia; “A Just Russia: Rodina / Pensioners / Life”; Agrarian Party of Russia; Party of Social Justice) | 2 (Civilian Power; Patriots of Russia) | 2 (REP The Greens; “New Course – Automotive Russia” bloc) | 12 | |

| 2011 | 7 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR; A Just Russia; Yabloko; Right Cause; Patriots of Russia) | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 2016 | 12 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR; A Just Russia; Yabloko; Party of Growth; Patriots of Russia; Russian Party of Pensioners for Justice; REP The Greens; People's Freedom Party; Rodina; Civilian Power) | 2 (Communists of Russia; Civic Platform) | 0 | 0 | |

| 2021 | 11 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR; A Just Russia; Yabloko; Party of Growth; Rodina; Russian Party of Pensioners for Justice; REP The Greens; Communists of Russia; Civic Platform) | 3 (New People; Russian Party of Freedom and Justice; Green Alternative) | 0 | 3 (Civilian Power; Patriots of Russia; People's Freedom Party) |

For mixed electoral systems, Scott Mainwaring applies a "weighted" score to calculate parties’ final results. It is calculated as follows: the percentage of votes a party receives under the proportional representation system is multiplied by the percentage of seats in the lower chamber allocated by that system; likewise, the percentage of votes a party receives under the majority voting system is multiplied by the percentage of seats allocated by that system; the two resulting values are then added together. For example, in the 1999 State Duma election, 50% of seats (225) were allocated through the proportional system, and 48% (216 seats, as deputies were not elected in nine constituencies) through the majority system. In those elections, the Unity bloc received 23.32% of the vote in the single nationwide constituency, whereas in the single-seat constituencies only nine of its nominees won seats. The combined result of all Unity candidates running in single-seat constituencies amounted to only 2.46% of the total votes cast for all party-affiliated and independent candidates in these constituencies. Accordingly, Unity’s "weighted" result equals 12.84 percent (23.32 * 0.5 + 2.46 * 0.48).

As for presidential elections (see Table 2), eight such contests have been held in Russia to date. In each of these elections, the presidential race included a candidate who may be regarded as representing the incumbent Russian authorities. That said, several parties nominated such a candidate in 1991; groups of voters did in 1996 and 2000. In 2004, 2018, and 2024, such contenders stood as independents. In 2008 and 2012, they were nominated by the "party of power" (United Russia).

In the 1991 and 1996 elections, Boris Yeltsin was supported by a broad coalition of political organizations which, despite formal differences, remained essentially the same. In 1991, such a coalition could be loosely associated with the Democratic Russia movement (which officially nominated Yeltsin alongside the Democratic Party of Russia and the Social Democratic Party of Russia). In 1996, it could be associated with the All-Russian Movement for Public Support of B. Yeltsin in the presidential elections (ARMPS), which included the “Our Home – Russia” movement as well as several other parties [13: 353]. For this reason, we treat Yeltsin in 1996 as a candidate nominated by an old party.

Likewise, in this article (including for the purposes of calculating the various indicators of Russia’s party system institutionalization) Vladimir Putin is treated as the representative of the dominant "party of power" in place at the time, notwithstanding that he was not formally nominated by parties in most electoral campaigns and did not hold formal party membership. Vladimir Putin is also viewed as Yeltsin’s successor, having been publicly designated as such by Yeltsin himself. Furthermore, this study proceeds from the assumption that Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin were both supported by one and the same broad "party of power", which may have incorporated different formal parties at various historical stages but is regarded as a single structure across the full sequence of presidential (but not legislative) elections. Consequently, Vladimir Putin is classified as an old candidate in the 2000 presidential election (whereas the Unity bloc is designated a new party in the 1999 legislative election).

The assumption that Vladimir Putin is a candidate of the "party of power" is made for several reasons: 1) although specific "parties of power" (Unity, United Russia) did not formally nominate him, they explicitly declared their support for Vladimir Putin; 2) "parties of power" were created by members of the political elite with the purpose of promoting and implementing the platform of the candidate who planned to run for the presidency in the forthcoming electoral cycle (and who, in effect, was the principal contender for the office); as a result, the candidate and the party became closely linked to one another [6; 21]; 3) the evolution of party systems in European countries, as well as in most Latin American ones, demonstrates that systems naturally arrive at a configuration in which virtually all candidates for head of government (prime minister or president, respectively) are party members and are nominated by parties, while self-nomination becomes increasingly rare.

Leaders of other parties who formally ran for the Russian presidency as independents or as nominees of voter initiative groups are likewise regarded in this article as representatives of their respective organizations. For example, Konstantin Titov (2000) and Irina Khakamada (2004) are treated as candidates of the Union of Right Forces; Sergey Glazyev (2004) as a candidate of Rodina; and Andrei Bogdanov (2008) as a candidate of the Democratic Party of Russia. The same principle applies to other candidates nominated by citizen initiative groups who nonetheless belonged to political organizations.

The 2012 presidential candidates also included Mikhail Prokhorov as an independent. Prior to that, he had spent roughly three months (in the summer of 2011) as the leader of Right Cause. In September 2011, he was removed from the post. Subsequently, in the December 2011 legislative election, Right Cause secured 0.6% of the vote, while Prokhorov received 7.98% in the March 2012 presidential election. From both a formal standpoint (Prokhorov was no longer a member of Right Cause at the time of the national election) and an ideological one (his electorate proved to be far broader than that of Right Cause), Mikhail Prokhorov cannot be regarded as a representative of Right Cause. Accordingly, in this article he is categorized as a candidate of a new party (Mainwaring refers to such participants as "independents", treating them as nominees of an unnamed new party).

In the 1991 presidential election, several candidates representing the CPSU (the future CPRF) competed simultaneously. According to Mainwaring’s codification, when such individuals belong to the same party, that party is treated as the nominating actor and the electoral results of its representatives are combined.

Aman Tuleyev ran in both the 1991 and 2000 presidential election. In 1991, he is considered as a candidate of the CPSU (having been a member of the party for over twenty years, up until the dissolution of the USSR), whereas in 2000 he is classified as a candidate of a new party (he was nominated by a voter initiative group). In his last presidential campaign, Tuleyev campaigned against the Communist candidate, Gennady Zyuganov. According to experts, by 2000 the governor of Kemerovo Oblast Aman Tuleyev had distanced himself from the CPRF, opted for cooperation with the federal center, and had begun to support the "party of power" in his region [26; 30].

The classification of parties as old or new across different types of elections – legislative and presidential – is carried out separately. In other words, a party may disappear from the political system following legislative elections while still continuing to participate in presidential elections, and the opposite scenario is likewise possible. For instance, the Russian All-People’s Union last took part as an independent organization in the 1999 State Duma election and is thus regarded as having exited the configuration of legislative elections; nevertheless, it remained within the configuration of presidential elections, as it later nominated its own candidate in 2018.

It should also be noted that A Just Russia, Yabloko, and Communists of Russia continue to exist. However, the last time a candidate from A Just Russia ran in a presidential election was in 2012, and the last presidential candidates from Yabloko and Communists of Russia appeared in 2018. Since the 2024 presidential election is the most recent to date, it remains unknown whether candidates from these three parties will take part in any future presidential contests. Therefore, following Mainwaring’s criteria, A Just Russia is classified as a party that has disappeared from the structure of presidential elections as of the 2018 contest. Yabloko and Communists of Russia are likewise classified as disappeared parties as of the 2024 election. However, any such party would be reclassified as "old" if its candidate were to participate in a future presidential election, in which case subsequent calculations would change accordingly.

Table 2. Party categorization in presidential elections

| Year | Old parties participating in the elections | New parties participating in the elections | Old parties absent in these elections but present in previous and at least one subsequent election | Disappeared parties previously participating | |

| 1991 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1996 | 4 (ARMPS; CPRF; LDPR; Yabloko Association) | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2000 | 5 (Unity; CPRF; LDPR; Yabloko Association; Union of Right Forces bloc) | 6 | 2 (Congress of Russian Communities movement; “Power to the People!” bloc) | 4 | |

| 2004 | 5 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR; Union of Right Forces; Rodina bloc) | 1 (Russian Party of Life) | 1 (Yabloko) | 6 | |

| 2008 | 4 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR; Democratic Party of Russia) | 0 | 1 (Rodina bloc) | 2 (Union of Right Forces; Russian Party of Life) | |

| 2012 | 4 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR; A Just Russia) | 1 (Mikhail Prokhorov) | 0 | 1 (Democratic Party of Russia) | |

| 2018 | 6 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR; Yabloko; Party of Growth; Russian All-People's Union) | 2 (Communists of Russia; Civic Initiative) | 0 | (A Just Russia; Mikhail Prokhorov) | |

| 2024 | 3 (United Russia; CPRF; LDPR) | 1 (New People) | 0 | 5 |

Scott Mainwaring calculates the vote share of new parties and their candidates, as well as mean and cumulative electoral volatility, using the formula proposed by Eleanor Powell and Joshua Tucker [27], which itself is an optimized version of Mogens Pedersen’s classic formula [25]. A significant drawback of the mathematical expression devised by Pedersen is that from the very beginning it was intended only for democratic states with stable party systems. In such countries, the core set of political parties is already established, and elections merely rotate the principal actors in and out of power. Voter preferences remain stable, ideological niches are filled, and there is simply no space for new parties to occupy.

However, in countries with underdeveloped and weak party systems, the political realities are fundamentally different. For this reason, Powell and Tucker expanded the existing formula for electoral volatility. They divided volatility into two subtypes: Type B and Type A. Type B volatility corresponds to volatility as understood by Mogens Pedersen and is described as "extra-system". It occurs "when voters switch their votes between existing parties. This type of volatility is considered to be a healthy component of representative democracy, and essentially reallocates power between political actors that are already, by and large, a relevant part of the political process" [27: 124]. Type A volatility, by contrast, is characterized as "extra-system." It is associated with fluctuations in the party system and reflects "new parties entering the political system – which by definition will not have had any voters in the previous election – and old parties exiting the political system, which by definition will not have any voters in the current election" [27: 127]. The sum of these two types of volatility represents overall electoral volatility.

The final formula is as follows:

\(V = \frac{ \sum_{o=1}^m p_{o,t} + \sum_{w=1}^l p_{w, t+1} } 2 + \frac{ \sum_{i=1}^n | p_{i,t} – p_{i,t+1} |} 2\) ,

where \(V\) is overall electoral volatility; \(i\) denotes parties that participated in two consecutive elections; \(n\) is the number of such parties; \(o\) denotes old disappeared parties that participated only in the previous election \(t\); \(m\) is the number of such parties; \(w\) denotes newly emerged parties that participated only in the current election \(t+1\); \(l\) is the number of such parties; \(p\) is the vote share received by a given party in the previous election \(t\) or in the current election \(t+1\).

In the majority of cases, Scott Mainwaring measures party system institutionalization in Latin American countries starting with the second election that follows the initial, founding election. In this context, he understands “founding election” as the first semi-democratic or democratic election conducted in a new state after the collapse of the preceding authoritarian regime. Founding elections are excluded from the calculation of extra-system volatility and of the vote shares of new parties and their candidates, because at the moment such elections take place all (or most) parties are only coming into existence and thus are categorized as new. Therefore, patterns of stability or variability within the party system cannot be observed immediately following the founding election; these processes emerge only through the outcomes of subsequent ones.

Nevertheless, as Mainwaring notes, there are instances in which the very first election precedes or follows the founding one. For example, in Chile the first election was held in 1989 and the founding election in 1990, whereas in Brazil the first election took place in 1986 and the founding election in 1985 [19]. Many Russian political scientists [5; 22: 170–176] regard the 1993 legislative election as Russia’s founding election. While this article concurs with that view, it also takes into account the exceptions to the rule noted by Mainwaring. Thus, for the purposes of this study, the first initial election after the establishment of the new competitive regime is defined as the RSFSR presidential election held in June 1991, whereas the founding election is defined as the 1993 legislative election (consequently, the calculation of PSI indicators for Russia begins in 1996 for presidential elections and in 1995 for legislative elections).

One further nuance must be noted. If a new party first participated in a legislative election and a candidate from that party subsequently ran in a presidential election, such a candidate is still regarded as new. Although the party is already known by the time of the second nationwide election, the two types of elections are different (legislative and presidential, respectively, and the same principle applies when the sequence of nationwide elections is reversed). However, if a new party participates in two (or more) legislative elections and then a candidate from that party competes in a presidential election for the first time, that candidate will no longer be identified as new, and his or her results will affect within-system rather than extra-system volatility.

Thus, for example, Aleksandr Lebed qualifies as a new candidate in the 1996 presidential election, since his movement (the Congress of Russian Communities) first entered the political arena in the 1995 legislative election. Grigory Yavlinsky, on the other hand, is classified as an old candidate: Yabloko nominated its first presidential candidate only in 1996, but the party had already participated in the legislative elections of 1993 and 1995.

All indicators presented in this study are based on the official electoral results of parties and presidential candidates [1; 8; 32]. The principles and formulas used for the final calculation of the parameters fully correspond to the rules established by Scott Mainwaring and his coauthors [17; 18; 19].

Using the available data, let us proceed to determining the empirical level of institutionalization of Russia’s party system.

Research findings

In the first block, “Stability in the membership of the party system participants”, Scott Mainwaring proposes calculating two parameters: the “Vote share of new-party candidates in presidential elections” and the “Vote share of new parties in lower chamber elections”. These indicators show how effectively newly created parties and their candidates have managed to enter the electoral arena and displace already existing parties. If new contenders are successful in their challenge to parties that may have existed for generations, the overall dynamics of the party system accelerate (although its instability also increases).

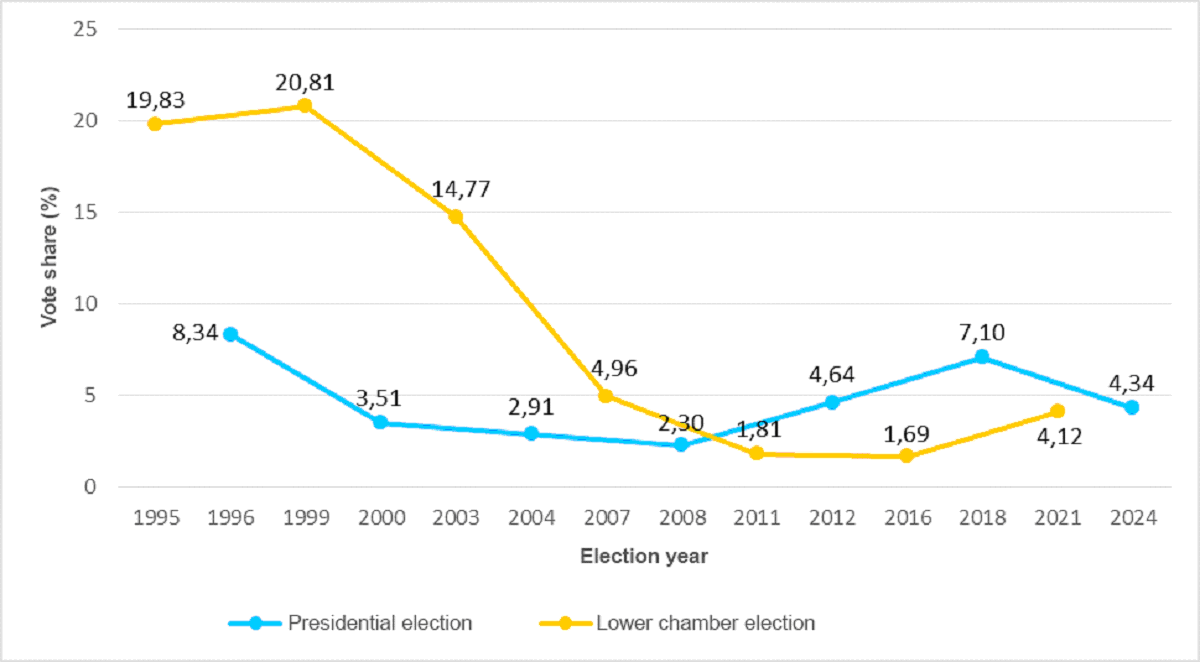

As a result, the Russian indicator for the vote share obtained by candidates of new parties in presidential elections equals 4.7%. In other words, in the entire post-Soviet period (1991–2024), candidates of newly created parties received on average 4.7% of the vote in each presidential election (Figure 1). This Russian indicator is two and a half times lower than the mean value (12.1%) of the general dataset (which includes eighteen Latin American countries, the United States, and Russia). A similarly low result (comparable to Russia’s) was observed for candidates of new parties in Costa Rica, Panama, the United States, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic.

In the case of elections to the lower chamber, the Russian indicator equals 9.7%. That is, in each State Duma election held between 1993 and 2021, newly created parties obtained 9.7% of the vote on average (Figure 1). This indicator is one-third higher than the average value for the group of countries used for comparison in this article (7.2%). New parties achieved roughly similar vote shares in Paraguay, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and El Salvador.

Twenty years ago, however, the vote share of new parties in State Duma elections (or extra-system electoral volatility) was twice as high at 18.5% (for the period 1993–2003) according to our calculations. At that time, this result was roughly identical to the average obtained by new parties in legislative elections in Eastern European and post-Soviet states (19.9%, 1990–2006, 14 countries including Russia). Yet the figure was many times higher than in Western Europe, North America, and Oceania (2.2%, 1945–2006, 20 countries) [17: 4–5]. Today’s indicator of 9.7% still lags significantly behind the level of institutionalization observed twenty years ago, which was typical of states with strong party systems.

Fig. 1. Vote shares of new parties and their candidates

Mainwaring then operationalizes the indicators "Stable participation of significant contenders, election-to-election (presidential)" and "Stable participation of significant contenders, election-to-election (lower chamber)". In a deeply entrenched, highly institutionalized party system, the same long-established parties – and their candidates, whether recurring individuals or different nominees of the same organization – compete across successive elections. By contrast, in a fluid and weakly institutionalized system, leading actors tend to exit the arena with each new electoral cycle, to be replaced by newly created parties and their respective candidates. Mainwaring defines a "significant contender" as a party or candidate that receives 10% or more of the vote in the relevant election (legislative or presidential). "Stable participation" refers to a party or its candidate repeating this success – that is, again obtaining 10% or more – in the next election of the same type.

Across the entire period of Russian presidential elections (1991–2024), candidates from the same party achieved this threshold in thirteen instances, receiving at least 10% of the vote in two consecutive presidential contests. At the same time, various candidates surpassed the 10% threshold a total of fifteen times between 1991 and 2018. The most recent presidential election at the time of writing – 2024 – may appear not to be included, even though, strictly speaking, it is incorporated into the calculation. This is because, although elections occur in specific calendar years, over an extended time period they constitute a single, continuous sequence. Thus, the end of the period under study simultaneously serves as the beginning of the next period, should a similar analysis be undertaken in the future. In such cases, to avoid error and prevent counting the same election twice, the initial election of the study period is included, whereas the last election of that period is, at first glance, not counted.

Thus, for Russia the index equals 0.87 (Table 3). The term "repeat contender" refers to candidates from the same parties who, in the present election, were able to confirm the stability of their performance by once more obtaining 10% or more of the vote, as they had in the previous election. The Russian index slightly exceeds the average score for Latin America, the United States, and Russia (0.73). It is comparable to the relatively high indicators of El Salvador, the United States, Costa Rica, Chile, and the Dominican Republic.

Table 3. Stable participation of significant contenders, election-to-election (presidential)

| Year | DemRussia; ARMPS; Unity; United Russia | CPRF | Rodina | Repeat contenders |

| 1991 | Х | Х | - | - |

| 1996 | Х | Х | Х | 2 out of 2 |

| 2000 | Х | Х | - | 2 out of 3 |

| 2004 | Х | Х | - | 2 out of 2 |

| 2008 | Х | Х | - | 2 out of 2 |

| 2012 | Х | Х | - | 2 out of 2 |

| 2018 | Х | Х | - | 2 out of 2 |

| 2024 | Х | - | - | 1 out of 2 |

| Total no. of repeat contenders | - | - | - | 13 out of 15 (0.87) |

Throughout the entire period of State Duma elections from 1993 to 2021, there were twelve instances in which parties obtained at least 10% of the vote in two successive legislative elections (the calculation relies on each party’s "weighted" result rather than its vote share in the nationwide constituency). At the same time, during the period from 1993 to 2016, various parties surpassed the 10% threshold on seventeen occasions in total. Thus, for Russia the index equals 0.71 (Table 4). It falls slightly short of the corresponding value for the group of countries under consideration (0.8). Similar figures are observed for Nicaragua, Paraguay, Ecuador, Guatemala, and Panama.

Table 4. Stable participation of significant contenders, election-to-election (lower chamber)

| Year | Choice of Russia | United Russia | CPRF | LDPR | Fatherland – All Russia | Rodina, A Just Russia | Repeat contenders |

| 1993 | Х | - | - | Х | - | - | - |

| 1995 | - | - | Х | - | - | - | 0 out of 2 |

| 1999 | - | Х | Х | - | Х | - | 1 out of 1 |

| 2003 | - | Х | Х | - | - | - | 2 out of 3 |

| 2007 | - | Х | Х | - | - | - | 2 out of 2 |

| 2011 | - | Х | Х | Х | - | Х | 2 out of 2 |

| 2016 | - | Х | Х | Х | - | - | 3 out of 4 |

| 2021 | - | Х | Х | - | - | - | 2 out of 3 |

| Total no. of repeat contenders | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12 out of 17 (0.71) |

The two indicators that complete the first block are "Medium term stability of significant contenders, from one election to the next, presidential elections" and "Medium term stability of significant parties, from one election to the next, lower chamber elections". These indicators show the likelihood that a candidate of the same party in presidential elections – or, correspondingly, a party in legislative elections – that has previously obtained at least 10% of the vote in any past election will again secure at least 10% in any subsequent election of the same type (presidential or legislative, respectively).

The indicator is calculated using the following formula:

\(MTS = N / (P * (Е – 1))\) ,

where \(MTS\) denotes medium-term stability of results; \(N\) is the number of times that parties (or their candidates) which had obtained at least 10% of the vote in any previous election reached this threshold again in any subsequent election; \(P\) is the number of parties (or their candidates) that received 10% or more of the vote in the corresponding elections (legislative or presidential); and \(E\) is the total number of elections (legislative or presidential). The denominator represents the maximum number of cases that would be possible if all parties (or their nominees) that had ever obtained at least 10% of the vote were to receive no less than 10% in every subsequent election without exception. Under such conditions, the ideal medium-term stability of results for all significant contenders would equal 100%. The lowest possible value, equal to 0, arises when no party (nor any of its candidates) ever again reaches the 10% threshold.

For Russian presidential elections, the index that measures the composition of significant contenders in the inter-election period is 0.62. Using the values presented in the table "Stable participation of significant contenders election-to-election (presidential)", the index is calculated as follows: 13 / (3 * (8 – 1)). The formula is derived from the observation that Russia has held eight presidential elections to date; that only candidates from three parties have obtained more than 10% of the vote in these elections; and that, following their initial attainment of this threshold, the nominee of the "party of power" exceeded it on seven subsequent occasions, while the CPRF nominee did so on six (7 + 6 = 13). In turn, the index indicates that, across the entire period of Russian presidential elections, a party candidate who has obtained at least 10% of the vote in any past presidential election has a 62% probability of again receiving no less than 10% in a future presidential election. Russia’s value exceeds the mean index of the entire twenty-country dataset (0.45) by more than one-third. This value corresponds to the strong indicators observed in the United States, Chile, El Salvador, Honduras, and Brazil.

In turn, for the State Duma elections Duma, this index equals 0.31. Using the values presented in the table "Stable participation of significant contenders election-to-election (lower chamber)" the index is calculated as follows: 13 / (6 * (8 – 1)). The formula is derived from the observation that Russia has held eight State Duma elections to date, in which only six parties have ever surpassed the 10-percent vote threshold. After initially surpassing this threshold, United Russia exceeded it five more times, the CPRF six more times, and the LDPR twice (5 + 6 + 2 = 13). Thus, the index implies that across the entire history of State Duma elections, a party that at some earlier point gained at least 10% of the vote has a 31% likelihood of attaining no less than this number in a subsequent legislative election. Our country's value is nearly twice below the average of the corresponding index computed for the states analyzed (0.53). It is also close to the specific values of Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Costa Rica, and El Salvador.

It is worth emphasizing that the six parameters comprising the “Stability in the membership of the party system participants” block exhibit an internal and mutually congruent relationship. In the case of presidential elections, the value of the first indicator is inversely proportional to the values of the third and fifth indicators, and in the case of legislative elections, the value of the second indicator is inversely proportional to the values of the fourth and sixth. Indeed, a low vote share for new parties or their candidates signifies stable participation of significant contenders and stable composition of electoral participants, and vice versa.

In order to compare levels of party system institutionalization across Latin American countries and the United States, Scott Mainwaring therefore calculates an indicator known as the standardized score, or Z-score. This score makes it possible to assess the extent to which the party systems of different countries are more or less stable relative to one another.

The Z-score shows how far (in terms of standard deviations) a particular value is from the mean of the overall distribution. A positive Z-score indicates that an individual value is above the mean; a negative score indicates that it is below the mean; and a score of zero signifies an equal correspondence to the mean. The parameter is calculated using the following formula:

\(Z = (X – \mu) / \sigma\) ,

where \(X\) is a particular element of the sample; \(\mu\) is the arithmetic mean; and \(\sigma\) is the standard deviation.

Mainwaring also notes that the mathematical signs ("+" and "–") of the Z-scores for the six indicators ("Vote share of new-party candidates in presidential elections", "Vote share of new parties in lower chamber elections", "Mean electoral volatility in presidential elections", "Mean electoral volatility in lower chamber elections", "Cumulative electoral volatility in presidential elections", and "Cumulative electoral volatility in lower chamber elections") must be reversed (from plus to minus or vice versa), so that a positive Z-score signals stability of the party system, whereas a negative value indicates its fragility.

To more accurately determine the degree of institutionalization of Russia’s party system and to identify its relative standing (at least within a selected group of countries), we map Russia within the overall dataset alongside the Latin American countries and the United States (Table 5).

Table 5. Stability in the membership of the party system participants (Z-score)

| Country | Vote share of new parties | Stable participation of significant contenders election-to-election | Stability of significant parties, from one election to the next | Mean Z-score | |||

| President | Parliament | President | Parliament | President | Parliament | ||

| Uruguay | 1.03 | 1.13 | 1.33 | 1.15 | 2.11 | 1.67 | 1.40 |

| Mexico | 0.97 | 0.64 | 1.33 | 1.15 | 2.11 | 1.53 | 1.29 |

| USA | 0.88 | 1.50 | 0.89 | 1.15 | 0.83 | 1.67 | 1.15 |

| Dominican Republic | 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 0.75 | 1.45 | 1.42 | 1.11 |

| Chile | 0.32 | 1.17 | 0.34 | 0.92 | 0.41 | 1.53 | 0.78 |

| Honduras | 0.48 | -0.11 | 1.33 | 1.15 | 0.18 | -0.12 | 0.49 |

| Brazil | 1.09 | 0.73 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.47 |

| Costa Rica | 0.65 | -0.38 | 0.98 | 0.34 | -0.09 | -0.37 | 0.19 |

| El Salvador | 0.32 | -0.20 | 0.79 | 0.29 | 0.18 | -0.37 | 0.17 |

| Nicaragua | 0.44 | 1.28 | 0.25 | -0.75 | -0.06 | -0.33 | 0.14 |

| Panama | 0.65 | 1.16 | -0.74 | 0.11 | -0.64 | -0.30 | 0.04 |

| Russia | 0.74 | -0.53 | 0.67 | -0.52 | 0.64 | -0.80 | 0.03 |

| Paraguay | -0.02 | -0.56 | -0.74 | -0.29 | -0.48 | -0.30 | -0.40 |

| Colombia | -1.58 | -1.14 | -0.98 | 0.52 | -1.06 | -0.48 | -0.79 |

| Bolivia | 0.12 | -0.66 | -0.98 | -1.73 | -0.68 | -0.90 | -0.81 |

| Ecuador | -1.15 | -0.84 | -0.49 | -0.87 | -0.71 | -0.83 | -0.82 |

| Peru | -1.35 | -1.55 | -0.93 | -2.08 | -0.64 | -1.12 | -1.28 |

| Argentina | -1.03 | -1.57 | -1.26 | -1.29 | |||

The table is not fully displayed Show table

The second block of indicators, "Stability of inter-party competition", begins with the parameters "Mean electoral volatility in presidential elections" and "Mean electoral volatility in lower chamber elections". These indicators are calculated as a standard arithmetic mean: the volatility scores for all elections, except for the first one, are summed (i.e., for Russian presidential elections from 1996 to 2024, or State Duma elections from 1995 to 2021), and the total is divided by the number of such elections.

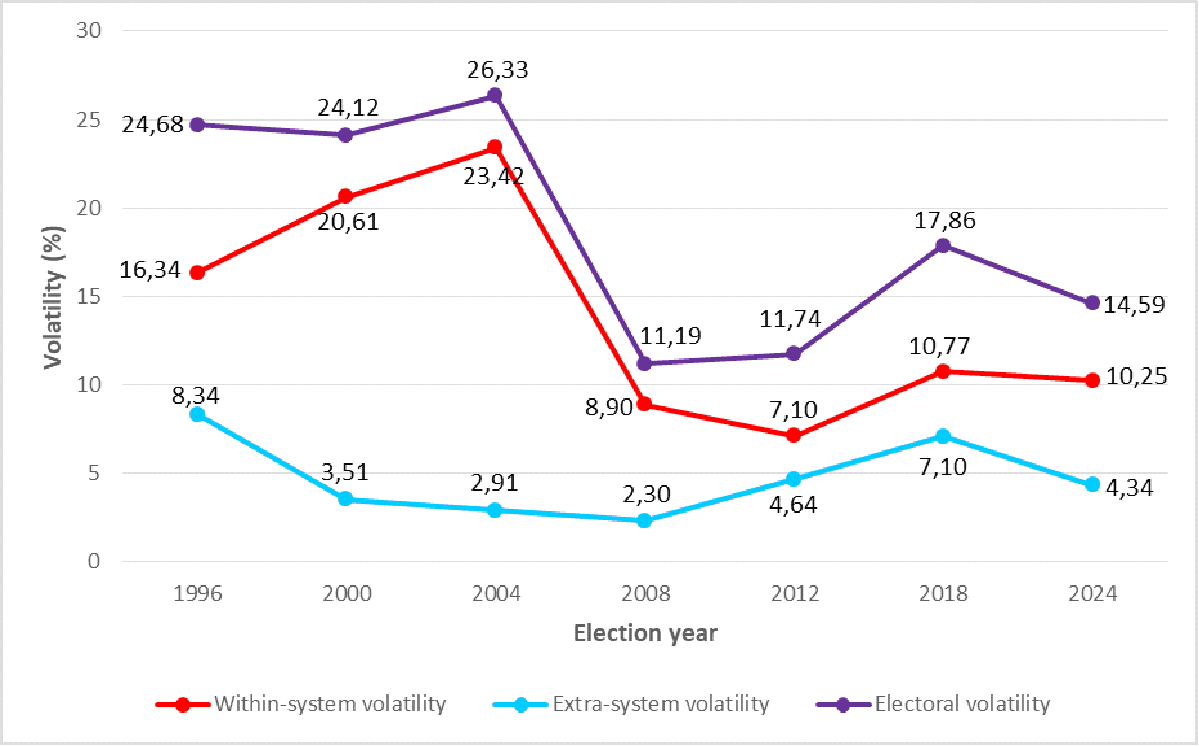

For Russian presidential elections, the indicator equals 18.6% (including average within-system volatility of 13.9% and average extra-system volatility of 4.7%) (Figure 2). This indicator is almost two times lower than the aggregate average electoral volatility in presidential elections for the group consisting of Latin American countries, the United States, and Russia (32.1%). It is comparable to the values recorded for Costa Rica, Mexico, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, and Honduras.

Fig. 2. Electoral volatility in presidential elections

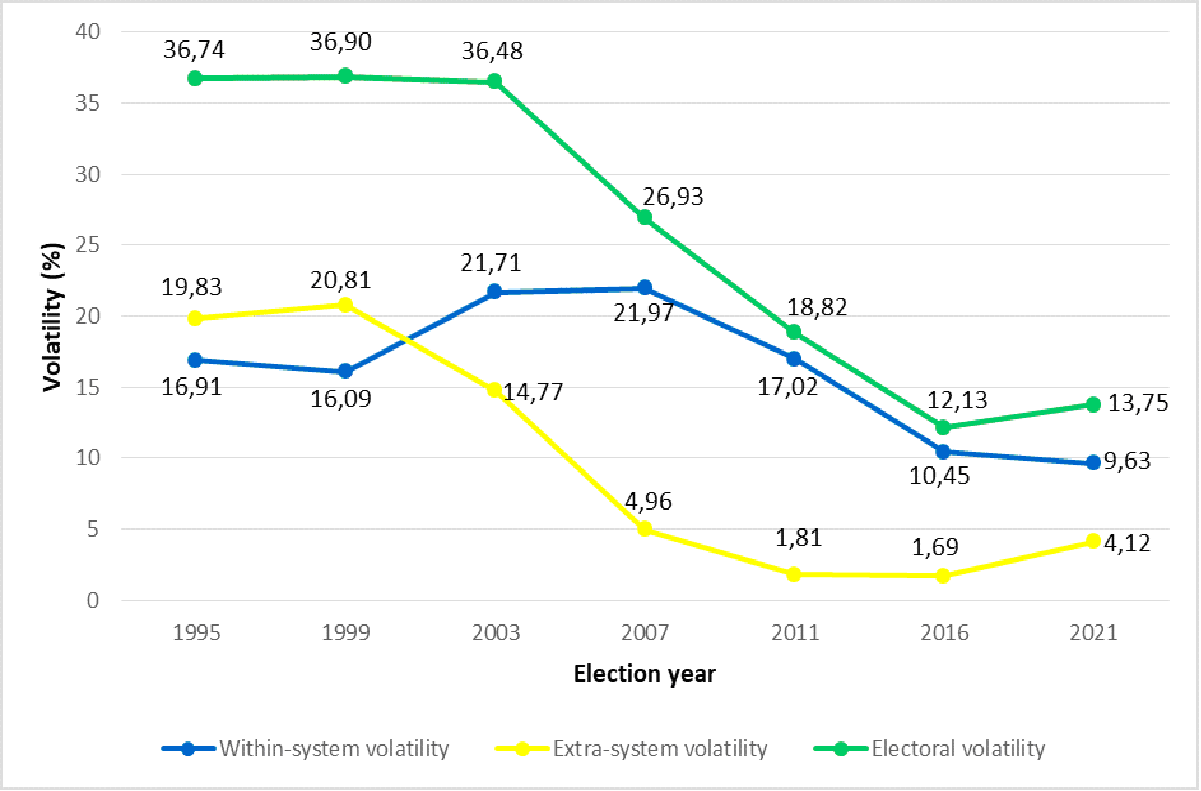

For State Duma elections, the indicator equals 26% (including average within-system volatility of 16.3% and average extra-system volatility of 9.7%) (see Figure 3). This level of volatility is virtually identical to the average electoral volatility in lower chamber elections characteristic of the entire group of countries under comparison (24.9%). The value is close to the ones observed in Paraguay, Colombia, Panama, the Dominican Republic, and Ecuador.

Twenty years ago, however, the average electoral volatility in State Duma elections amounted, according to our calculations, to 36.7% (1993–2003). At that time, a similar level of volatility was observed in parliamentary elections across Eastern European and former Soviet states (43%, 1990–2006, 14 countries including Russia). Yet the indicator was several times higher than in Western Europe, North America, and Oceania (10.7%, 1945–2006, 20 countries) [17: 4–5]. The contemporary Russian indicator has declined substantially, yet it still remains far from the level characteristic of states with stable party systems.

Fig. 3. Electoral volatility in lower chamber elections

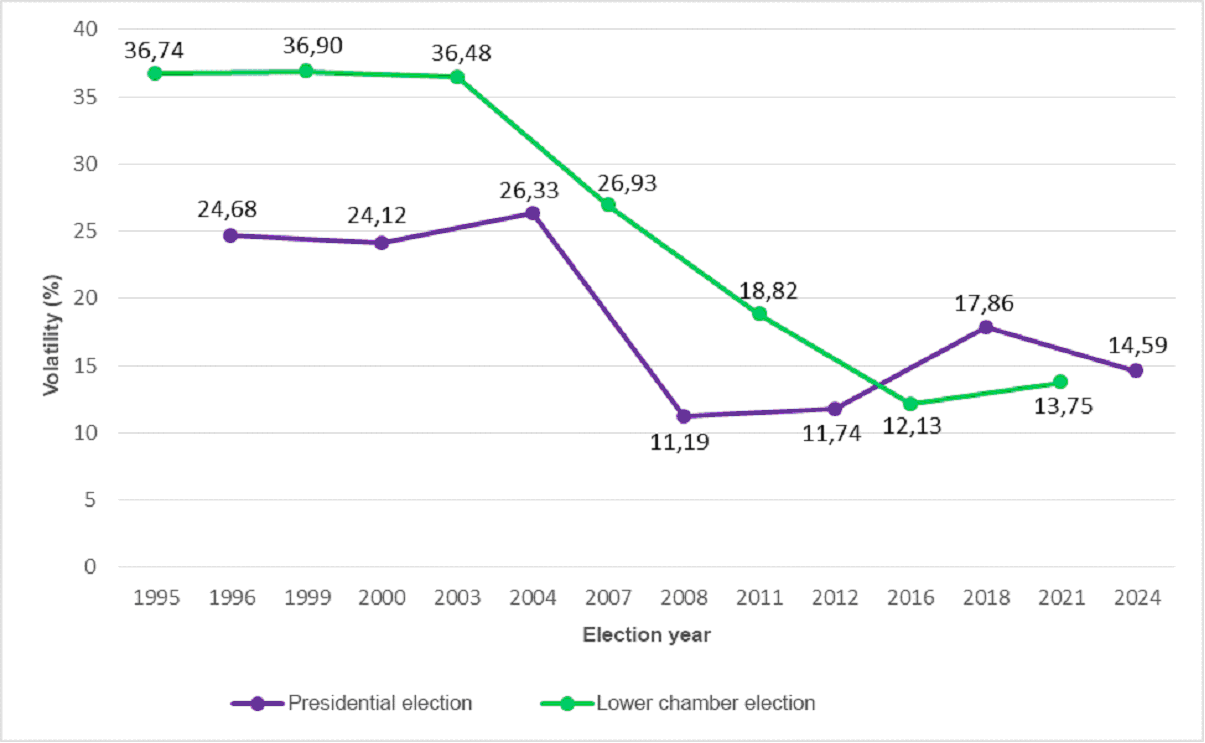

To better understand the process of the institutionalization of Russia’s party system, let us display electoral volatility in presidential and State Duma elections (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Electoral volatility in federal elections

The next pair of indicators consists of "Cumulative electoral volatility in presidential elections", and "Cumulative electoral volatility in lower chamber elections". Cumulative volatility is calculated in the same manner as standard volatility, except that the results of parties or their candidates are compared not across two consecutive elections, but between the earliest election and the most recent election to date.

Scott Mainwaring introduces cumulative indicators because conventional measures of electoral volatility do not capture changes accumulated over time. He offers the following example. Imagine two systems in which parties A, B, C, D, and E are functioning at the outset, in 1990, and where mean volatility in both systems equals 20% over the period from 1990 to 2015. In the first case, A, B, C, D, and E remain the only competitors, and by 2015 they return to the same vote shares they received in 1990. The mean volatility is 20%, yet cumulative volatility from 1990 to 2015 equals zero. In the second system, Party F replaces Party A in the second election, Party G replaces Party B in the third, Party H replaces Party C in the fourth, and so forth. Although mean electoral volatility is again equal to 20%, after five elections none of the initial parties is still present, and cumulative volatility rises to 100%. Hence, with identical mean volatility, the system remains intact in the first scenario but is completely reshaped in the second [18: 49].

Cumulative electoral volatility in Russian presidential elections equals 32.5% (including cumulative within-system volatility of 30.6% and cumulative extra-system volatility of 1.9%). This value is more than one-third lower than the corresponding mean indicator across the observed group of countries (53.9%) and is comparable to the figures recorded for Chile, El Salvador, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay.

In turn, cumulative electoral volatility in State Duma elections equals 63.4% (including cumulative within-system volatility of 10.1% and cumulative extra-system volatility of 53.3%). This value slightly exceeds the corresponding average indicator for the set of countries under consideration (54.6%) and is comparable to the levels observed in Colombia, Peru, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama.

The second block is concluded by the indicators "Vote share of old-party candidates in the recent presidential election" and "Vote share of old-party candidates in lower chamber elections." These indicators capture the proportion of votes received by old parties (or their candidates) among all parties contesting the most recent presidential or legislative elections; in both types of national elections, "old" refers to parties that already took part in the first presidential or parliamentary elections.

For presidential elections in Russia, this indicator equals 96.1%. This value is 1.7 times higher than the average for Ibero-American countries, the United States, and Russia (56.5%). It is one of the highest values in this set and approximates the maximum levels recorded in Mexico, Uruguay, the Dominican Republic, Paraguay, and the United States.

Vote share of old-party candidates in the most recent State Duma election equals 28.1%. This value is almost twice as low as the average indicator for the twenty countries under examination (52.2%) and corresponds to the levels observed in Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and El Salvador.

The indicators of the second block, which assess the stability of inter-party competition, are likewise compatible and mutually conditioned, just as the indicators of the first block capturing the stability in the membership of the party system participants. The sum of the two indicators – the cumulative electoral volatility (in presidential or legislative elections) and the share of votes received by old parties in the most recent election (presidential or legislative, respectively) – will approximate 100%. If this sum falls short of the 100% threshold, this indicates that new parties, or presidential candidates representing them, have not succeeded in replacing the old parties and their candidates that competed in the earliest elections under the new political regime. This situation is characteristic of Russian legislative elections: 63.4% + 28.1% = 91.5%. Accordingly, it may be argued that in the context of State Duma elections there exists a certain niche that could be filled by hypothetical contenders who have not yet entered the arena, thereby responding to electoral demand. If the combined value of the two indicators is approximately equal to 100%, one may conclude that new parties succeeded in persuading voters to support them and effectively outcompeted old parties. If the sum significantly exceeds 100%, this indicates that the electorate that had supported old parties in the earliest elections subsequently shifted to other old parties in the most recent election. This situation is characteristic of presidential elections in Russia: 32.5% + 96.1% = 128.6%. The higher the value rises above the 100% threshold, the greater the proportion of voters who have moved from one old party to another.

To determine the extent to which competition among Russian parties has stabilized and become institutionalized in comparison with party competition in the Latin American countries and the United States, we calculate the corresponding standardized score (Table 6).

Table 6. Stability of inter-party competition (Z-score)

| Country | Mean electoral volatility | Cumulative electoral volatility | Mean Z-score | ||

| President | Parliament | President | Parliament | ||

| USA | 1.62 | 1.85 | 1.23 | 1.78 | 1.62 |

| Uruguay | 1.41 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.17 | 1.16 |

| Mexico | 0.87 | 0.65 | 1.21 | 0.66 | 0.85 |

| El Salvador | 0.96 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 0.26 | 0.80 |

| Chile | 0.16 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 1.20 | 0.79 |

| Honduras | 1.26 | 0.88 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.72 |

| Dominican Republic | 0.63 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.78 | 0.53 |

| Brazil | 0.07 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.43 |

| Paraguay | -0.68 | -0.08 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.32 |

| Russia | 0.91 | -0.09 | 0.75 | -0.35 | 0.31 |

| Costa Rica | 0.91 | 0.42 | -0.38 | -0.38 | 0.14 |

| Panama | -0.82 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.10 | -0.02 |

| Nicaragua | 0.01 | -0.57 | 0.02 | -0.18 | -0.18 |

| Colombia | -0.52 | -0.41 | -1.18 | -0.37 | -0.62 |

| Argentina | -1.11 | -0.32 | -0.71 | ||

| Ecuador | -0.91 | -0.55 | -1.57 | -1.04 | -1.02 |

| Peru | -1.70 | -1.93 | -0.79 | -0.32 | -1.18 |

| Venezuela | -0.64 | -1.56 | -1.61 | -1.68 | -1.37 |

The table is not fully displayed Show table

At the same time, Scott Mainwaring maintains that two indicators – cumulative electoral volatility in legislative and presidential elections – almost perfectly correlate with two other indicators, namely the vote shares received by old parties and their candidates in the most recent legislative and presidential elections. In other words, treating these values jointly would effectively result in double "inflation" of what is essentially the same underlying indicator. Therefore, Mainwaring's calculation excludes the vote shares obtained by old parties (and their candidates) in the most recent elections.

The thirteenth and final indicator, "Stability in party linkage with society: Change in parties’ ideological positions", is considered separately. It demonstrates that when parties’ ideological positions change abruptly and substantially, the degree of party-system institutionalization declines. A radical ideological shift proves costly for a party, particularly in long-established systems where strong ideological linkages and programmatic attachments have formed between parties and voters. Among other consequences, the disruption of such linkages leads to an increase in electoral volatility.

Scott Mainwaring measures change in parties’ ideological positions on the basis of survey data involving members of national legislatures in Latin American countries, collected regularly since 1994. He argues that public opinion surveys are less effective for identifying parties’ ideological positions, as many citizens lack a clear understanding of the left to right scale [18: 54]. He also develops a formula that enables him to capture the ideological changes undergone by the entire party system within a given country.

The formula is as follows:

\(\frac{\sum_{i=1}^n {( |I_{i2} – I_{i1}| * V_{i2} / V_{all2} })^n} {1 – V_{new2}}\) ,

where \(|I_{i2} – I_{i1}|\) represents the change in the indicator measuring the ideological position of party \(I\) from the previous election \(T1\) to the current election \(T2\); \(V_{i2}\) denotes the share of votes received by party \(I\) in the current election \(T2\); \(V_{all2}\) is the total share of votes in the current election \(T2\) obtained by all parties for which data on ideological positions are available both for the previous election \(T1\) and the current election \(T2\); \(n\) is the number of parties for which such data on ideological positions are available for both \(T1\) and \(T2\); and \(V_{new2}\) is the aggregate vote share received by new parties in the current election \(T2\).

Unfortunately, in Russia, there is a lack of studies in which members of the State Duma would assess differences between the ideological or programmatic positions of the parliamentary factions. Nor are there long-term, regularly administered public surveys in which citizens could place parties on a left to right scale. Consequently, operationalizing and quantifying changes in the ideological positions of Russian parties proves extremely difficult; therefore, this indicator is not employed in the present article.

Nevertheless, Mainwaring is confident that the correlation among his thirteen PSI indicators is fairly high; therefore, the absence of one or several measures does not affect the final conclusions. Supporting this claim, he compares the indicators obtained in his most recent study (covering the period between 1990 and 2015) with those from an earlier investigation, in which he examined institutionalization in the same Latin American countries but over the previous period (1970–1995). At that time, he relied not on thirteen indicators, as he does now, but only on six [18: 59]. Therefore, in assessing the degree of institutionalization of Russia’s party system, it is acceptable, in the view of this article’s author, to omit one of the thirteen indicators.

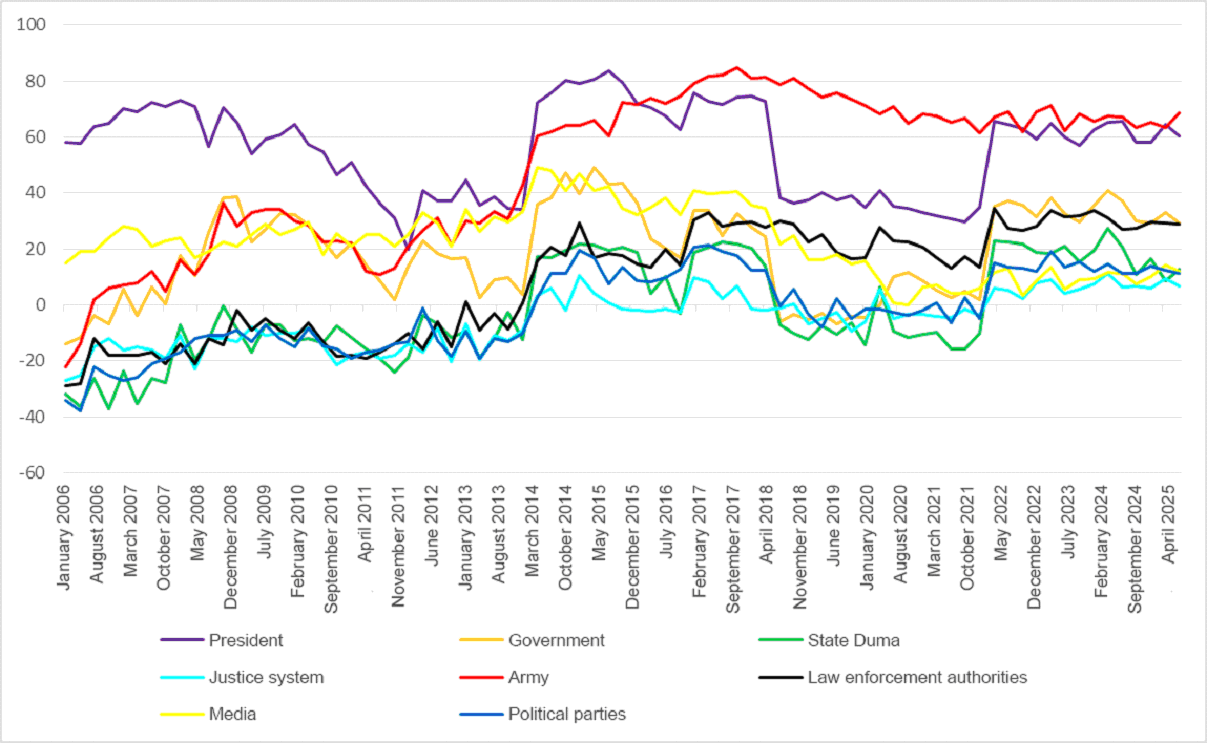

At the same time, there are a number of public opinion surveys in Russia that capture citizens’ attitudes toward state institutions and measure their approval ratings. According to these surveys, political parties do not enjoy high levels of public esteem. They are perceived by the population as dependent actors that do not aspire to an autonomous and influential role in politics: "First of all, it should be noted that Russians give a very low rating to the significance of parties as a political institution... After several electoral cycles in which the weight of parties within the political system declined substantially, and after several convocations of the Federal Assembly that offered no examples of solving pressing societal problems, Russians (who had initially begun to engage in political life and in party competition during the early congresses of the Supreme Soviet in the perestroika period) lost interest in it. Parties fail to attract the attention of Russians also because, to a considerable extent, they remain virtual or symbolic entities rather than real organizations with their own personnel, membership, readiness for concrete action, and other features that distinguish an actual public organization from a media phantom" [23].

The general trend indicates that trust in political parties as an institution has increased over time. However, parties continue to be perceived as relatively insignificant organizations when compared to most other state and social structures [3; 4]. The majority of Russian citizens continue to view parties primarily as a "facade" behind which more powerful political actors operate, and which functions merely as a "tribute" to globally accepted notions of how a political system ought to be organized (Figure 5).

Fig. 5. Index of approval of governmental and social institutions

Discussion and concluding observations

Scott Mainwaring proposed thirteen indicators for analyzing the level of institutionalization of party systems. Calculations performed according to his methodology show that, in the Russian case, half of the values exceed the average indicators for Latin American countries and the United States, while the other half fall below them. Of the twelve indicators (excluding the parameter "Stability in party linkage with society: Change in parties’ ideological positions"), six may be considered favorable for Russia, and all of them pertain exclusively to presidential elections (low vote share of new-party candidates in presidential elections; stable participation of significant contenders election-to-election (presidential); stable composition of significant contenders participating in presidential elections; low mean electoral volatility in presidential elections; low cumulative electoral volatility in presidential elections; and high vote shares of old-party candidates in the most recent presidential election). The corresponding indicators related to State Duma elections proved to be lower than the average values across the overall dataset.

To precisely determine Russia’s position within this group of countries, we present the cumulative Z-score that reflects the overall level of party system institutionalization in Russia, the Latin American countries, and the United States (Table 7). A highly positive Z-score indicates a stable and consolidated party system (relative to the given set of countries), a Z-score close to zero indicates a moderately institutionalized and fluctuating system with its own strengths and weaknesses, and a highly negative score reflects a fragile and underdeveloped system.

Table 7. Final valuess of party-system institutionalization in Russia, Latin American countries, and the United States (Z-scores)

| Country | Stability in the membership of the party system participants | Stability of inter-party competition | Stability in party linkage with society: Change in parties’ ideological positions | Final PSI value |

| USA | 1.15 | 1.62 | 1.39 | |

| Uruguay | 1.40 | 1.16 | 0.07 | 1.29 |

| Mexico | 1.29 | 0.85 | 1.63 | 1.19 |

| Chile | 0.78 | 0.79 | 1.95 | 0.93 |

| Dominican Republic | 1.11 | 0.53 | -0.90 | 0.75 |

| Honduras | 0.49 | 0.72 | 0.50 | 0.64 |

| El Salvador | 0.17 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.54 |

| Brazil | 0.47 | 0.43 | 1.04 | 0.53 |

| Russia | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.17 | |

| Costa Rica | 0.19 | 0.14 | -0.80 | 0.10 |

| Panama | 0.04 | -0.02 | 0.61 | 0.06 |

| Nicaragua | 0.14 | -0.18 | 0.21 | -0.01 |

| Paraguay | -0.40 | 0.32 | -1.42 | -0.15 |

| Colombia | -0.79 | -0.62 | -1.11 | -0.79 |

| Ecuador | -0.82 | -1.02 | -0.73 | -0.97 |

| Argentina | -1.29 | -0.71 | -0.30 | -1.02 |

| Bolivia | -0.81 | -1.39 | -0.25 | -1.12 |

| Peru | -1.28 | -1.18 | -1.54 | -1.35 |

| Venezuela | -1.43 | -1.37 | 0.59 | -1.36 |

The table is not fully displayed Show table

Some disagreement may arise regarding the assertion made in this article that Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin were classified as belonging to the same "party of power". If Vladimir Putin is treated as a candidate of a new party in the 2000 presidential election, then, after recalculating the values of multiple indicators, only three of them would ultimately outperform the average values for the reference set of countries (low vote share of new-party candidates in presidential elections; low mean electoral volatility in presidential elections and stable participation of significant contenders election-to-election (presidential)). The degree of institutionalization of the party system would become weaker, and the cumulative standardized score would amount to -0.24. Russia would move from ninth to thirteenth place out of twenty countries, although the countries with PSI levels comparable to Russia's would remain the same.

The level of institutionalization of a country’s party system can be identified using various indicators. Scott Mainwaring proposes his own set of conceptual and interrelated parameters that make it possible to compare countries according to the stability of their party systems.

This article pursued two objectives. The first was to use Mainwaring’s empirical methodology to determine the precise value of Russia’s PSI relative to Latin America and the United States. The findings indicate that Russia’s party system occupies an intermediate position within this pool of countries, comparable to medium-developed systems such as those of Costa Rica, Panama, Nicaragua, and Paraguay, and stands at a considerable distance from both the leading systems (Uruguay, Mexico) and the weakest ones (Venezuela, Guatemala). It should also be taken into account that PSI indicators for Ibero-American countries, when compared with the corresponding parameters of the firmly institutionalized party systems of Western Europe and North America, are themselves relatively low [18: 57, 65].

In order to obtain a more objective view of the level of PSI in Russia and other states, it is worth noting a limitation that potentially exists in Scott Mainwaring’s framework. It is reasonable to assume that a low level of party system institutionalization implies weak influence and a limited role of parties within the political system. Yet the assumption that a high level of institutionalization implies substantial influence and significance of parties may be questioned. A situation may arise in which, following the establishment of a new competitive regime and up to the present time, the very same old parties (and their candidates) continue to participate in elections, consistently obtaining substantial and stable electoral support, while almost no new challengers emerge. Such a pattern would formally indicate a high degree of party system institutionalization. Nevertheless, in practice this may prove otherwise. On the contrary, such a situation may reflect an extreme condition in which the party system is in a state of complete stagnation. Alternatively, it may indicate that both the party and electoral systems (under a semi-democratic regime) are subject to close control by a more powerful actor (for example, the executive branch), which, guided by its own interests, seeks to artificially maintain institutionalization at a more or less acceptable level (or even attempts to achieve the maximum possible degree of PSI).

Thus, it can be assumed that a dominant actor, through targeted intervention, is capable of regulating the formal level of party system institutionalization. However, despite such efforts, this does not render the party system genuinely stable, since precisely this manageability and dependence on such a powerful actor keep the system turbulent and fragile, preventing it from acquiring autonomous and structural stability. Scott Mainwaring’s indicators may fail to capture such interference, which, in turn, may constitute a fundamental characteristic of the country’s political system.

At the same time, the results of this study (which place Russia’s level of PSI at an intermediate position relative to Latin American countries and at a weak level relative to Western Europe) demonstrate that Mainwaring’s analytical framework produces reliable conclusions: they largely coincide with those of other scholars who examine Russian party development. Many of them emphasize the limited progress made by Russia’s party system in its institutional consolidation. Herewith, researchers tend to focus primarily on substantive factors, namely the influence, capacities, and independence of the Russian party system. In turn, Mainwaring’s algorithm is aimed at identifying the technical empirical level of PSI across different countries, which makes cross-national comparison easier. Potentially, these two approaches can complement each other.