A dual approach to proving electoral fraud using statistics and forensic evidence

Abstract

Electoral fraud often manifests itself as statistical anomalies in election results, yet its extent can rarely be reliably confirmed by other evidence. Here we report the complete results of municipal elections in the town of Vlasikha near Moscow, where we observe both statistical irregularities in the vote-counting transcripts and forensic evidence of tampering with ballots during their overnight storage. We evaluate two types of statistical signatures in the vote sequence that can prove batches of fraudulent ballots have been injected. We find that pairs of factory-made security bags with identical serial numbers are used in this fraud scheme. At 8 out of our 9 polling stations, the statistical and forensic evidence agrees (identifying 7 as fraudulent and 1 as honest), while at the remaining station the statistical evidence detects the fraud while the forensic one is insufficient. We also illustrate that the use of tamper-indicating seals at elections is inherently unreliable.

I. Introduction

Inclusive social institutions lead to long-term prosperity of a nation [50]. In their absence, it is crucial for the society to be informed of its current shortcomings, which is achieved via independent analysis and publicity. A fair election system is one of these institutes. Electoral fraud produces many types of statistical irregularities in election results that reveal it. This has become obvious with the advent of information technologies that allow easy access to and analysis of returns from individual polling stations [7; 17; 19; 26; 29]. Instances of fraud can occasionally be caught but are rarely documented at a scale and coverage comparable with that the statistics predicts, especially that this generally requires cooperation from the authorities [40]. Here we report municipal elections where both statistical analysis and recorded evidence of fraud (or lack thereof) is available for every polling station. They largely corroborate one another, although multiple statistical tests may be required to fully reveal the fraud when counterfeiters try to disguise it.

Statistical methods are based on clearly defined assumptions and thus allow independent verification. Analysing polling station returns allows one to detect anomalies in result–turnout distribution [17; 21; 29; 34; 36; 37; 41; 42; 43; 44], unwarranted exhaustion of blank ballots [32], dependence of election protocol values on the presence of an observer [10; 13; 14] or ballot scanner [18; 23; 24]. This yields a qualitative estimate of the scale of fraud. More rigorous statistical methods allow to calculate the probability of the anomaly occurring by chance, such as prevalence of integer percentage values in the returns [19; 20; 22; 48; 35]. This quantifies its cogency as evidence of fraud.

Our study introduces rigorous statistical analysis of the results of a physical manipulation of ballots, such as their stuffing and swapping. We calculate the probability they form long series of identical votes when they are being tallied and probability of an insufficient number of toggles observed. We analyse vote-counting sequences recorded by observers.

II. Experiment

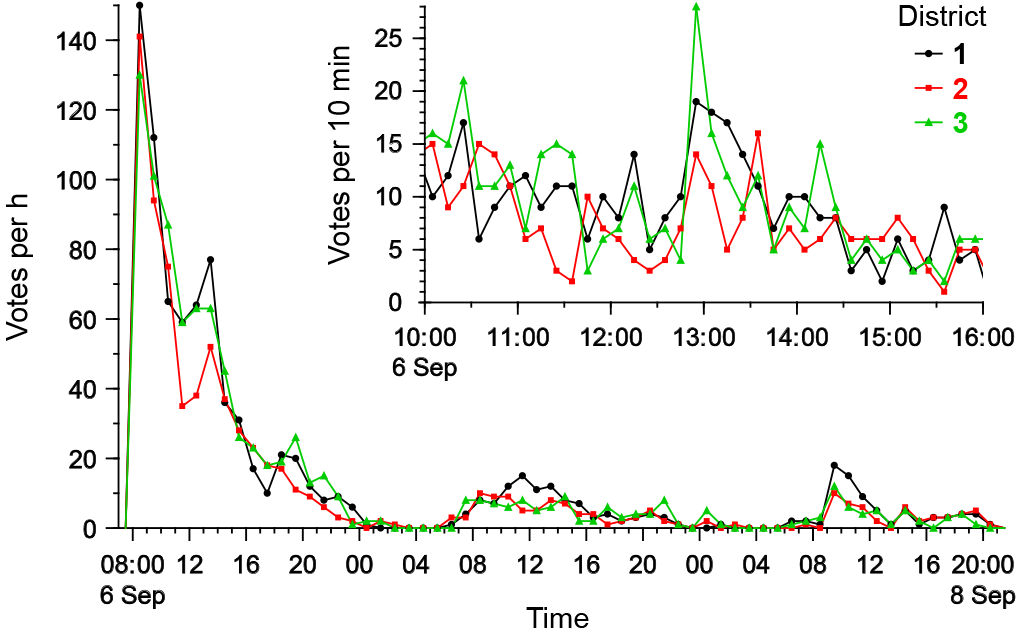

The elections of the town council in Vlasikha took place on 6–8 September 2024. They yielded unexpected data that prompted an otherwise unplanned study.

Vlasikha is a compact (less than 3 kilometers across), restricted-access community that serves the headquarters and main control center of the Russian intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) force [52]. The voters are a mix of civilians and military personnel.

The town, populated by \(17,189\) registered voters (of which 35% voted), is divided into 3 electoral districts of about equal size, each represented by 5 seats in the council of 15 total seats. In each district, \(c = 11\) individual candidates ran and each voter could select up to five of them in the ballot. The same number of candidates in each district is a coincidence. Although independent candidates were allowed, each candidate here was nominated by a party. The 5 candidates with the largest number of votes in the district got the seats.

Each electoral district is divided into 3 physical polling stations (precincts), as well as one virtual e-voting precinct where any voters preferring to cast their vote online could register in advance. The voting in all the precincts proceeded over 3 consecutive days. At the polling stations, each voter used a voting booth to mark his or her paper ballot in secrecy, had an opportunity to fold it to conceal the choices, and cast the ballot into a large transparent box standing in public view. At the end of the first and second day, all ballots cast in that day were extracted from the box, sealed inside a security tamper-evident bag (whose unique number was logged publicly) and stored in a safe in the room of the polling station until the vote counting. All the ballots were counted at the end of the third day.

Election officials manned the polling stations during the day. Candidates and observers were also present almost continuously, watched the procedures, made video recordings and took photos. By law, no one was allowed to remain at the polling station at night except police guards stationed outside the sealed room.

Unlike earlier Russian elections [10; 31], the presence of observers no longer impeded the fraud. Analysis of photographs and video recordings showed evidence of tampering with the security bags in 7 out of 9 precincts (table 1). Thus, the ballots inside the bags were likely replaced at night.

Table 1. Summary by precinct

| Electoral district | \(c\) | Precinct number | First day | Second day | \(n\) | Intentional mixing of ballots? | \(\textrm{p}\alpha'\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}'\) | Majority in this precinct | Got seats in this district | ||

| \(n_1\) | Evidence of tampering? | \(n_2\) | Evidence of tampering? | |||||||||

| 1 | 11 | 212 | 157 | positive | 117 | positive | 437 | yes | 4.0 | 4.3 | 5 UR | 5 UR |

| 213 | 104 | no record | 68 | positive | 256 | no record | 2.3 | 4.5 | 5 UR | |||

| 214 | 181 | inconclusive a b | 104 | positive | 388 | no | 9.8 | 18.4 | 5 UR | |||

| e-voting | 878 | 2 CP, 3 UR | ||||||||||

| 2 | 11 | 215 | 183 | negative c | 135 | negative c | 473 | no | 0.8 | 2.2 | 4 CP, 1 UR | 1 LD, 4 UR |

| 216 | 95 | positive | 86 | positive | 318 | yes | 3.6 | 21.0 | 1 LD, 4 UR | |||

| 217 | 108 | positive | 69 | positive | 290 | yes | 0.4 | 2.6 | 1 LD, 4 UR | |||

| e-voting | 726 | 2 CP, 3 UR | ||||||||||

| 3 | 11 | 218 | 435 | positive | 109 | positive | 577 | no | 10.9 | 9.3 | 1 JR, 4 UR | 1 JR, 4 UR |

| 219 | 131 | positive | 93 | inconclusive a | 355 | no | 18.7 | 20.2 | 1 JR, 4 UR | |||

| 220 | 129 | inconclusive a b | 84 | inconclusive a | 346 | no | 20.3 | 30.1 | 1 JR, 4 UR | |||

| e-voting | 844 | 2 CP, 3 UR | ||||||||||

\(с\), number of candidates; \(n_1\) (\(n_2\)), number of voters who obtained ballots in the room during the first (second) day; \(n\), total number of valid ballots announced during the vote counting; CP, Communist party; JR, a Just Russia party; LD, Liberal-democratic party; UR, United Russia party. Suspiciously high powers of significances are shown in bold (Appendix B1).

a – No visible changes in geometry of the security tape, with too poor image quality to locate its number.

b – Vote counting transcript supports a bag swap.

c – Recently procured bags with short 8-digit numbers are used, for which we have not observed duplicates.

During the vote-counting (tallying) procedure, the security bags were opened and their content stacked up with the ballots cast into the box during the third day. A varying amount of mixing between ballots from different days took place during the stacking-up, but was never a complete mixing. The ballots were then displayed and read aloud sequentially, and the votes counted manually, of which we have produced transcripts. These transcripts are amenable to statistical analysis and show strong evidence that the alleged replacement of ballots during the night has drastically changed the outcome of elections. While local opposition candidates nominated by the Communist party (CP) likely won the majority of the seats, they were all replaced with pro-administration candidates from other parties via the fraud [53].

III. Forensic evidence

Tamper-indicating seals have been known since the antiquity and are ubiquitous [15]. They are unsuitable for securing contemporary elections [3; 54]. In order for such security devices to be efficient, all the interested participants must be formally trained and adhere to a detailed use protocol for the seal [8; 16]. This is unrealistic at elections where the sides involved — candidates, observers, press, and precinct election officials — essentially consist of members of the general public. They attend the elections infrequently and have no time for such specific training. However, motivated fraudsters have months to prepare and can be well-funded.

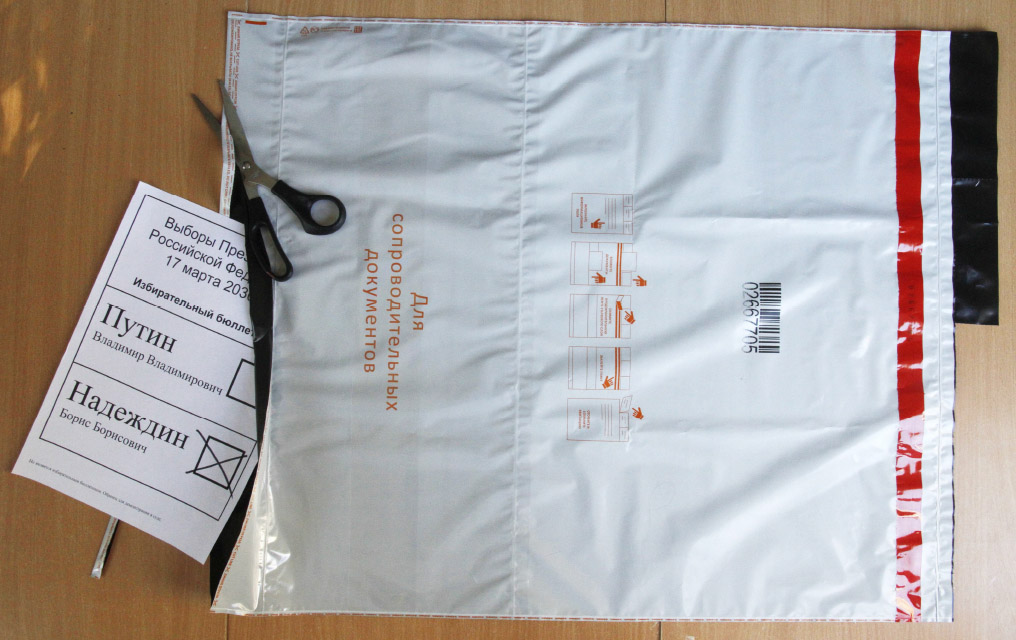

There are at least 5 methods for compromising the security bag (appendix C). Some of them can be done locally and some require the procurement of a factory-made duplicate.

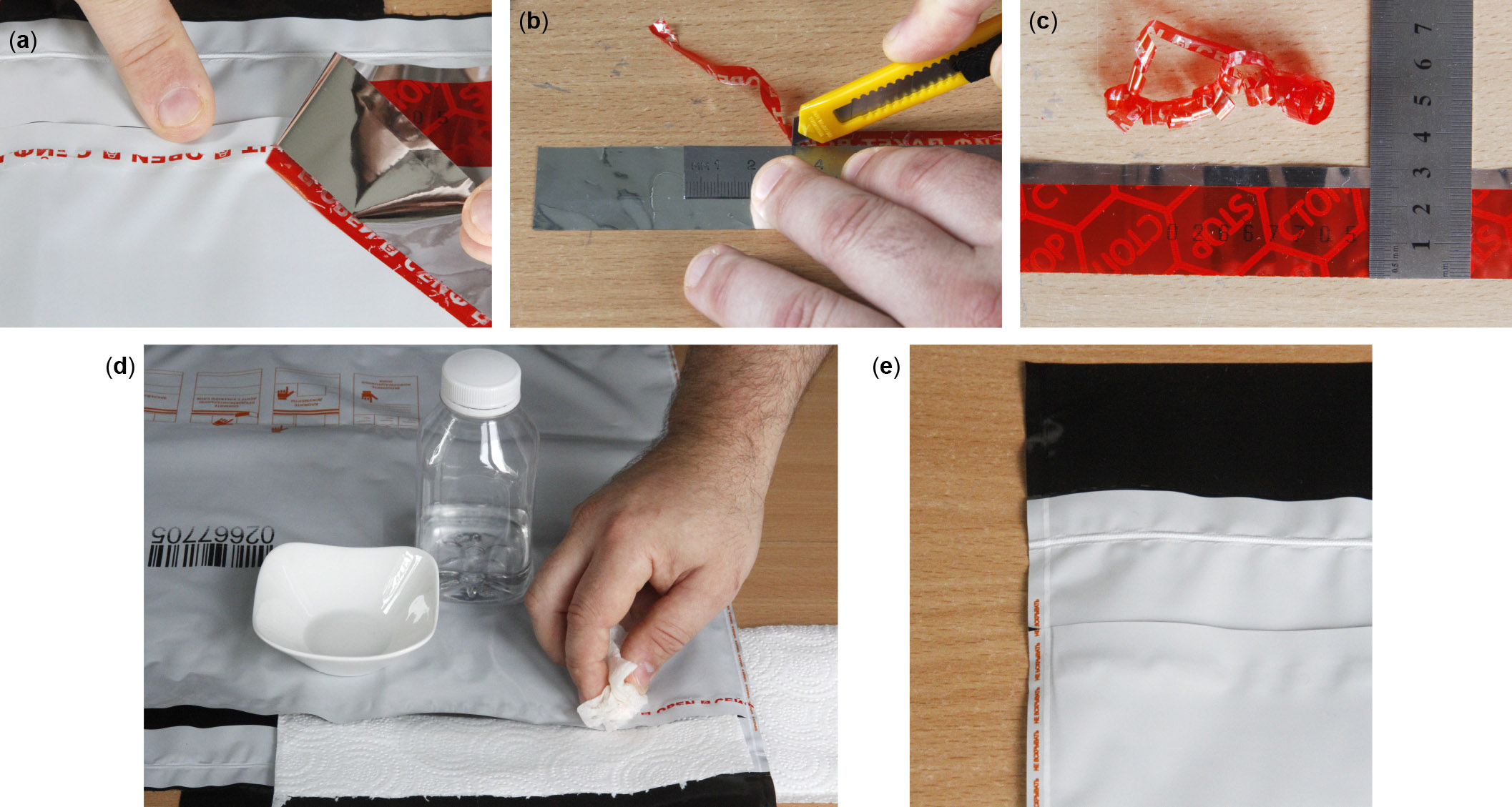

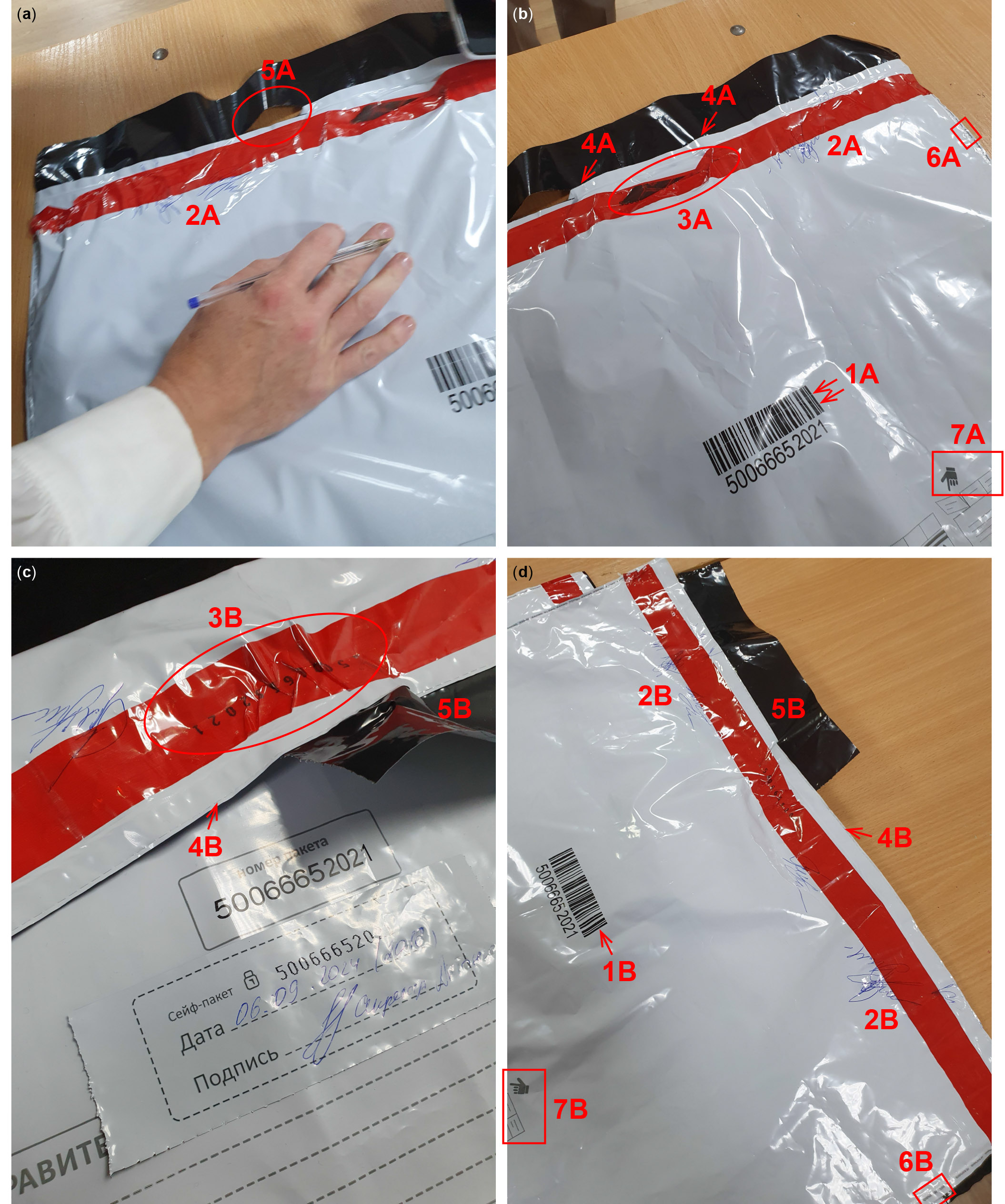

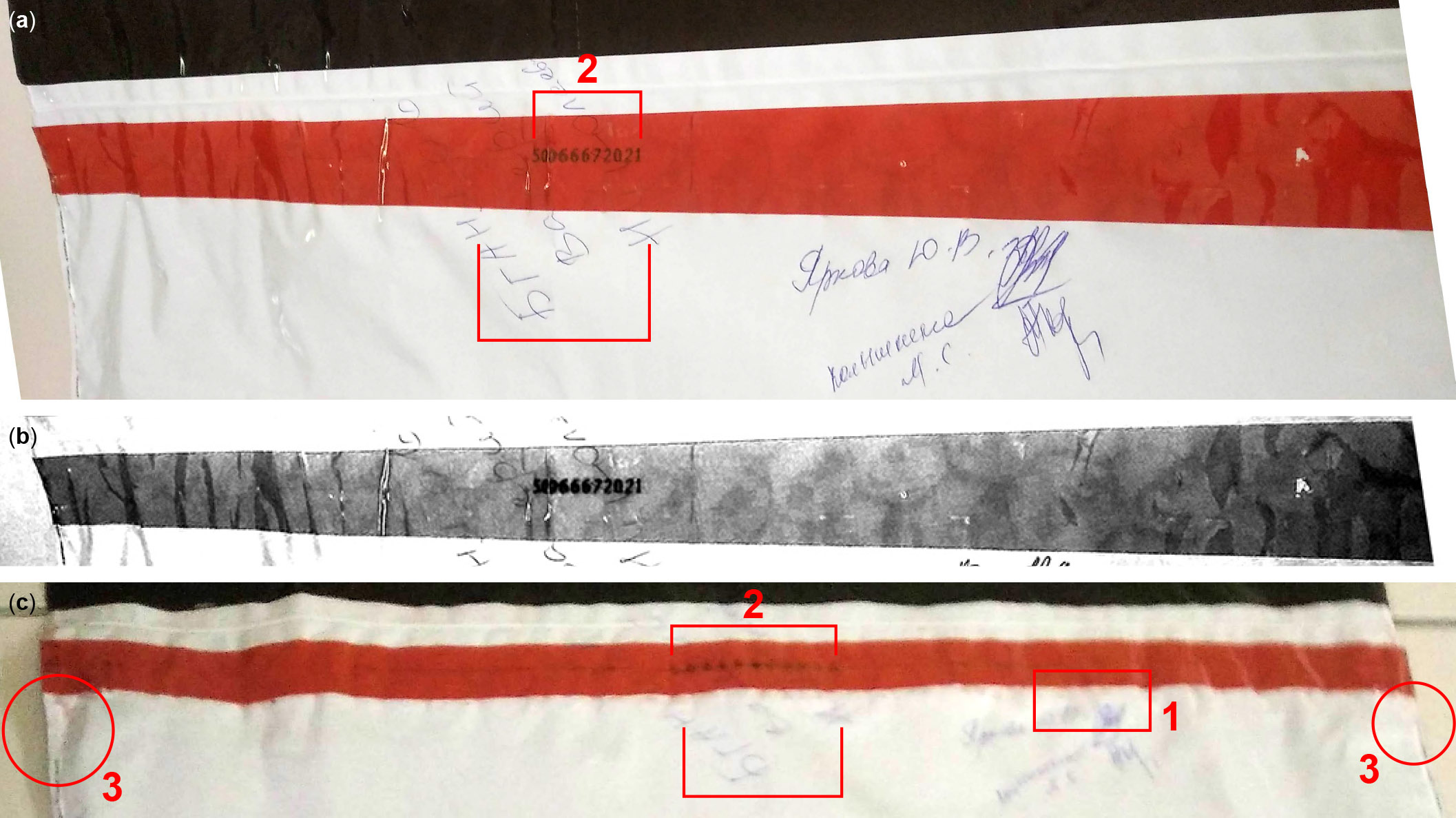

According to our reconstruction of the crime, the precinct commissions in Vlasikha had access to pairs of security bags with identical individual numbers (which were supposed to be unique but were actually made in two copies at the factory). At precinct 219, we have a conclusive photographic evidence of such pair of bags (appendix D1). At most other precincts, only tamper-evident sealing tapes were replaced, presumably to avoid forging pen signatures left on the bags by observers, candidates, and election officials. At night, the perpetrators entered the room without the observers or candidates being present (for which evidence is available at 3 precincts) and opened the safe (leaving visible traces on the safe at 2 precincts). They peeled off the original 30 millimeter-wide security tape from the bag, thus unsealing it, and allegedly swapped the ballots. Tamper-evident adhesive remaining from the tape's removal was cleaned from the bag using solvent, as detailed in appendix C. Another security tape with identical number, cut off from the unused duplicate bag (losing 5 to 10 millimeters of its width in the process), was then applied to reseal the bag.

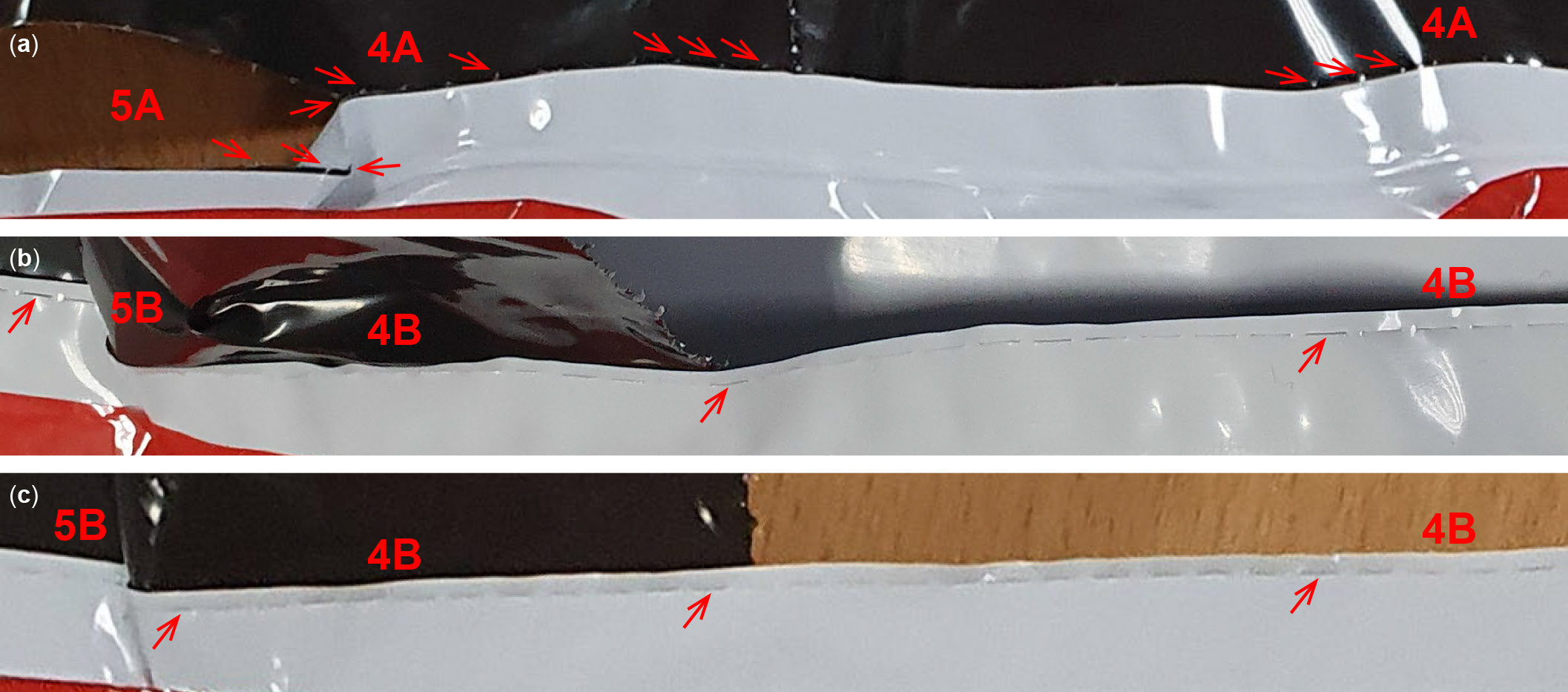

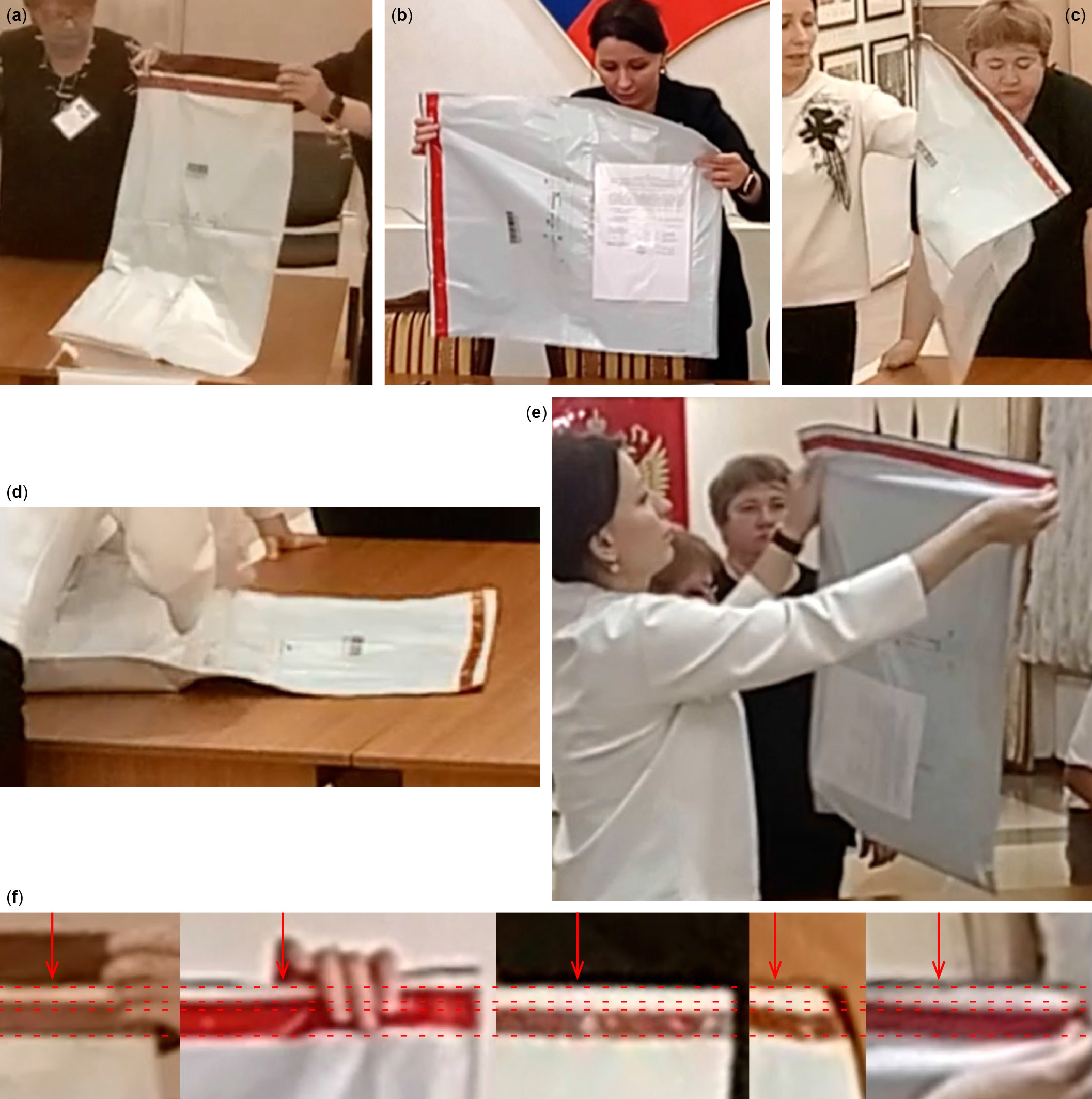

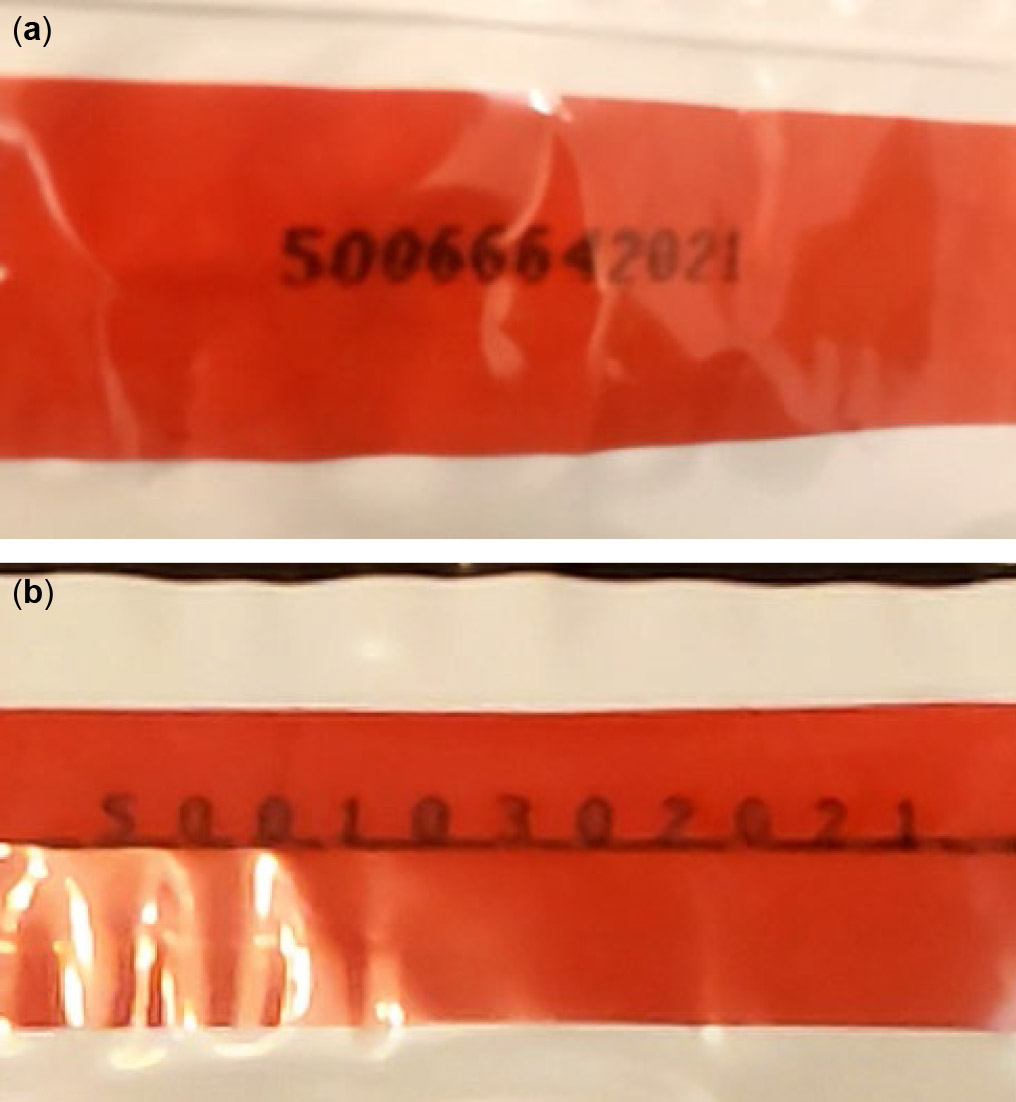

The fraud succeeded in the sense that the bag numbers matched those logged, while the visual appearance of the tapes and bags raised suspicion from no one during the hectic voting days. The election outcome was certified immediately [53]. However, despite these tamper-evident bags being only a modest security measure [2] not designed to resist the availability of a factory-made duplicate with identical number [12], they eventually worked as intended. A meticulous examination and cross-check of video recordings and photographs taken during the voting days showed the sealing tape and the area around it looking differently at 7 precincts (see example in fig. 1), is inconclusive at precinct 220, and indicates the lack of tampering at the remaining precinct 215. Remarkably, at precinct 219 we see that not only the tape but the entire bag was swapped for its full factory-made duplicate — complete with its identical individual number — and pen signatures were forged. This was discovered and understood slowly, weeks after the elections. In total, at least 11 bags containing 1479 ballots were tampered with (see table 1 и appendix D).

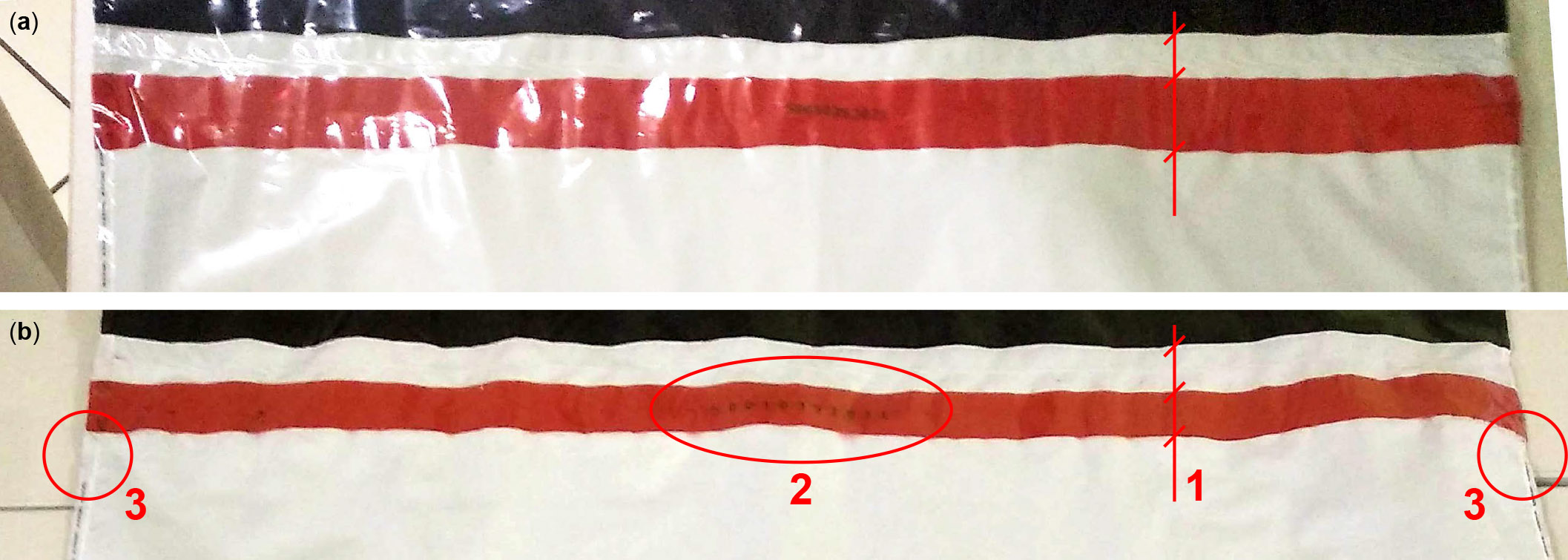

Fig. 1. Red sealing tape on the security bag at precinct 212 (a) after sealing the bag on the second day and (b) before opening it during the vote tallying on the third day. Note (1) changed tape width and placement relative to the upper edge, (2) increased intersymbol space and overall width of the unique number, changing from normally-typeset to sparsely-typeset, and (3) disappeared factory-printed line of text at the bag's edges, presumably removed with solvent.

IV. Statistical analysis

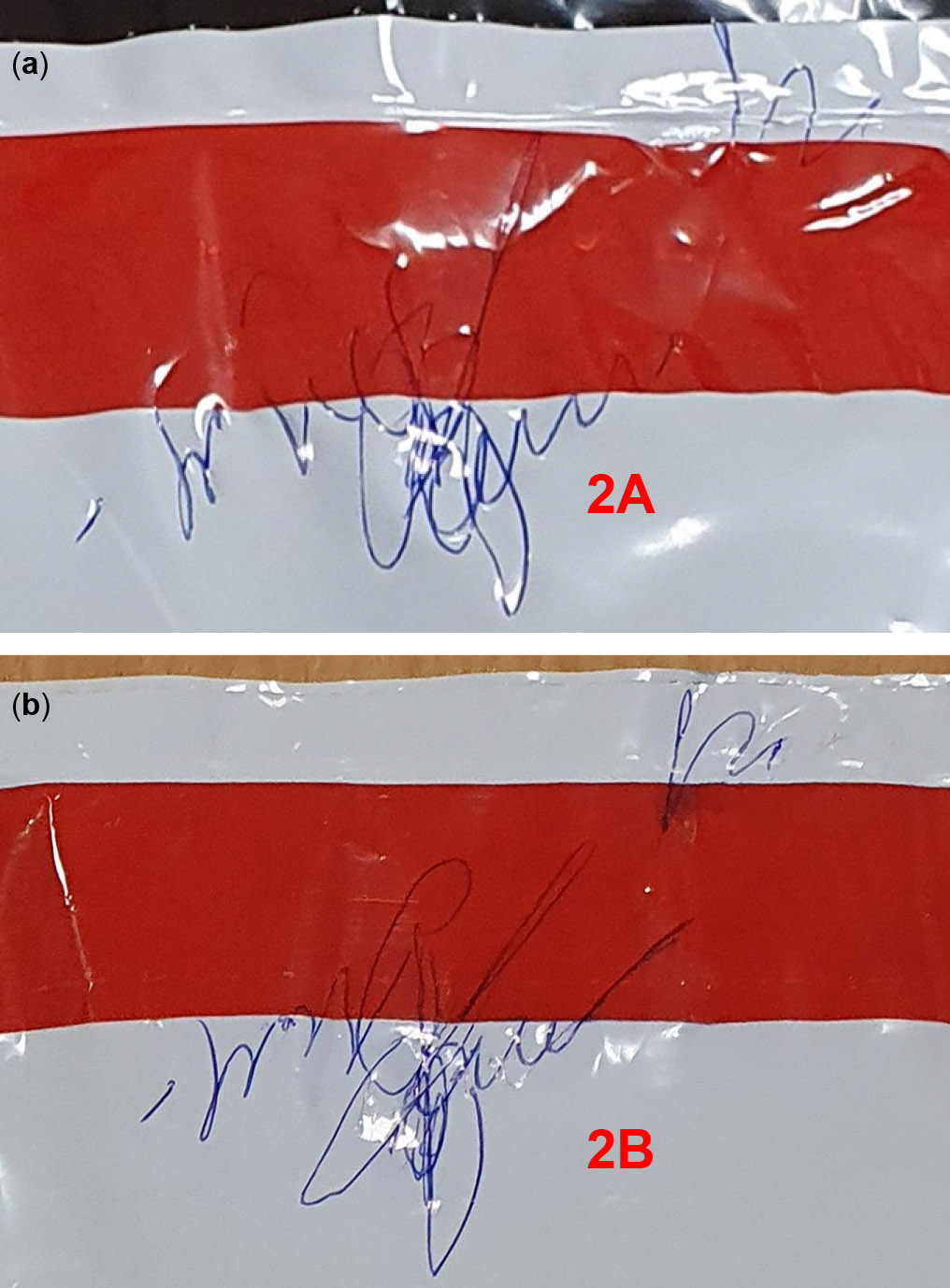

The transcript of vote counting for precinct 215 (fig. 2 left pane) has a random distribution of votes throughout, without any visible features. Transcripts for all the other precincts display irregularities, of which a typical example is precinct 220 shown in fig. 2 right pane. A random vote sequence (with a clear prevalence of votes for 5 opposition candidates nominated by CP) is interrupted by three packs of identical ballots for 5 pro-administration candidates (1 JR's nominee and 4 UR's nominees). Incidentally, there are 129 ballots in total for these 5 candidates, while the bag from the first day also contains 129 ballots. This raises a suspicion that nobody in reality voted for this particular set of candidates, and the long sequences of identical ballots came from that bag.

Fig. 2. Transcripts of vote counting for 2 precincts: 215, where we have not observed any evidence of fraud, and 220, where swapping the bag containing 129 ballots is alleged. Top 5 candidates at each precinct are shown in bold. The least probable series is denoted by a red (grey) line.

Since almost all the other transcripts (shown in appendix A) display similar visual patterns, we have designed two simple statistical tests.

In the first test, we calculate significances \(\alpha_1\) and \(\alpha_0\). These are the probabilities of the longest observed continuous series of votes and absences of votes to occur naturally for a candidate at the precinct. Such extremely long series are assumed to result from stuffing batches of identical ballots.

In the second test, we calculate a significance \(\tilde{\alpha}\). It is the probability that the number of continuous series arising naturally does not exceed their observed number. A long series can be broken by partial mixing of ballots prior to their counting. However even in this case, the transcript contains fewer toggles between series of votes and absences of votes than statistically expected, which this test should detect.

For these calculations, we make two assumptions. Firstly, we conservatively assume that all the ballots are genuine. This allows us to calculate the probability for a voter to cast or not cast a vote for the candidate. Secondly, we assume that successive ballots are mutually independent. Even if small groups of like-minded voters (such as families and friends) come to vote at the same time, their ballots are randomly distributed when deposited into the box and then again when extracted from the box. This should help maintain the independence of ballots in the vote-counting sequence.

These significances are computed by an iterative calculation, as detailed in appendix B, which also lists their values for every precinct and candidate. With these values, we proceed to a summary analysis for the precincts. If any of the probabilities \(\alpha_0\), \(\alpha_1\), or \(\tilde{\alpha}\) turns out to be small, this indicates ballot stuffing. The evidence of such electoral fraud can be provided by the smallest significances obtained for the candidates running in the precinct \(\alpha_{\min} = \min_{c}\left\{\alpha_0, \alpha_1\right\}\) and \(\tilde{\alpha}_{\min} = \min_{c}\tilde{\alpha}\). However, in order to correctly characterise the general state of affairs at the precinct, one should take into account multiplicity testing and introduce an appropriate correction. The point is that the more attempts are made to calculate some random variable, the higher the natural chances that it will at least once take on a very small value.

When \(c\) candidates run in the precinct, the significance of the hypothesis that the least probable number of series arose naturally doesn't exceed \(\tilde{\alpha}'=1-(1-\tilde{\alpha}_{\min})^{c}\approx c \tilde{\alpha}_{\min}\). Using the approximation here is appropriate if \(\tilde{\alpha}_{\min}<10^{-8}\), to avoid loss of accuracy in computations. Similarly, the significance of the hypothesis that the least probable continuous series arose naturally doesn't exceed \(\alpha'=1-(1-\alpha_{\min})^{2c}\approx 2 c \alpha_{\min}\). The factor of \(2\) here accounts for each candidate being counted twice for two types of series (votes and absences of votes).

We ignore the possibility here of obtaining low significances multiple times at the precinct. This eliminates the need to analyze the similarities and differences between candidates. Such simplification may overestimate the overall significances \(\alpha'\) and \(\tilde{\alpha}'\). This weakens our test, which is acceptable. So we may risk missing violations, but we do not risk making unfounded accusations.

When the fraud is present, the significances tend to have very small values. It is more convenient to list not the values \(\alpha\), but their powers \(\textrm{p}\alpha=-\lg\alpha\) (similar to \(\textrm{pH}\) in chemistry). Remember that the probability of no fraud drops by an order of magnitude for each increase of the power value by \(1\). The powers of the overall significances are listed in table 1.

For 5 precincts, the probabilities are extremely low, less than \(10^{-9}\) (i.e., \(\max{\left\{\textrm{p}\alpha', \textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}'\right\}} > 9\)). This certainly indicates the presence of fraud, as the chance the precinct is honest is less than one-in-a-billion. Higher probabilities in the remaining 4 precincts can either be explained by mixing the ballots before they are counted (such that fraudulent long sequences are broken into sufficiently many fragments), the presence of intentionally introduced random ballots in the original fraudulent sequence, or the precinct being free from this type of fraud.

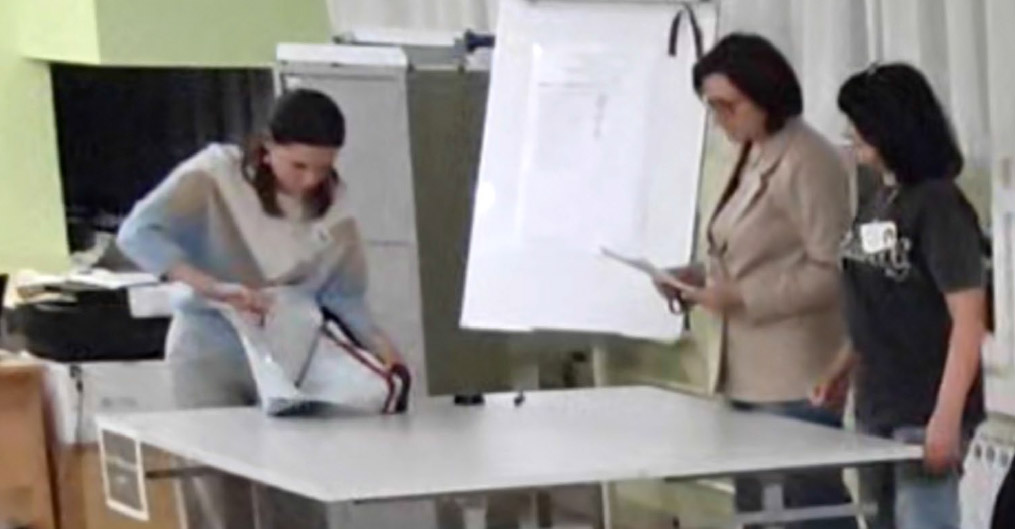

After extracting the ballots from the bags and boxes on the third day, the commissions verified and removed invalid ballots (those with no marks or more than 5 marks) before the vote counting. To speed up this step, the check was done by several commission members simultaneously, each working a fraction of the ballots. When they added the checked ballots into the final stack, it was done in chunks. This step alone usually introduced some shuffling. In addition, some commissions intentionally mixed the ballots by spreading them into a single heap on a table, stirring the heap and randomly turning over handfuls of ballots (which was recorded in our videos and noted in table 1). We think that moderately low probabilities at precincts 212 and 213, and high at 217 are due to such intentional mixing. The high but still suspicious probability \(\tilde{\alpha}'= 6.2 \times 10^{-3}\) at precinct 215 might be owing to one of our assumptions being not entirely correct, e.g., maybe the ballots are not entirely mutually independent. More data from honest precincts should clarify this in future studies.

Evidence of statistical nature, even with quite high probability of error, is admissible in courts [5; 11]. Notably, Russian courts accept a genetic paternity test having the error probability of no more than \(10^{-3}\), provided that the mother is known for certain (otherwise, the threshold for the error probability is relaxed to \(2.5 \times 10^{-3}\)) [39]. Using this approach, electoral fraud should be considered established at all precincts except 215 and 217. However, we advocate a stricter threshold. As discussed above, fraud is definitely detected at precincts 214, 216, 218, 219, and 220, where \(\min{\left\{\alpha', \tilde{\alpha}'\right\}}<10^{-9}\).

While it may appear that precinct 217 evades fraud detection, our test can be improved to consider ballots with marks for all 5 top candidates. This test reveals the fraud there with \(\tilde{\alpha} = 5.9 \times 10^{-15}\) and gives non-suspicious values for the honest precinct 215 (see appendix B3).

Overall, after our careful analysis of statistics and transcripts (appendix A), we know what happened overnight to all but one of the 18 security bags used in these elections. In addition to the 11 bags visibly tampered with table 1 and appendix D), 2 more were replaced, as continuous sequences of identical ballots show: the first bag at precincts 214 and 220. 4 bags remained uncompromised: both bags at precinct 215 and the second bag at precincts 219 and 220. We are only uncertain about the first bag at precinct 213.

Unlike the physical polling stations, e-voting precincts allow little insight into their operation. They lack data on the vote counting process and offer no evidence of tampering with ballots (appendix E).

V. Discussion and conclusion

We have introduced rigorous statistical tests of the vote-counting sequence that do not make any non-trivial assumptions about the voters' characteristics. These tests detect the ballot-replacement fraud in most cases, which is corroborated by separate forensic evidence.

Results from the 3 e-voting precincts, one honest precinct, and our analysis of the eight fraudulent precincts reveal tightly contested elections, with pro-administration and opposition candidates running closely. The latter de facto won about half or possibly more than half the council seats. The genuine voter turnout is 35%, which is unusually high for Russian municipal elections and shows the people's interest in its outcome. Through the ballot swap, an unlikely combination of pro-administration candidates was installed in the council and the local opposition lost all the seats it previously held.

We note that a less rigorous analysis [33], which assumes typical voter characteristics, allows reconstruction of the real results. It predicts a council with 9 CPRF-nominated and 6 UR-nominated members, in agreement with the present study.

Such blatant fraud is possible only under conditions of complete legal impunity of the perpetrators. Unfortunately, our experience so far shows this is the case. Multiple complaints to the election commissions of all levels were dismissed. Crime reports to the local police and the Investigative committee of the Russian Federation citing the evidence presented in appendixes C and D, have been dismissed as not worthy investigation. The police guarding the polling stations at night has reported nothing. Courts dismissed four initial lawsuits on a technicality. The head of the local police, head of the state prosecutor's local office, deputy political officer of the ICBM force, and town major all attended the first meeting of the newly elected council and congratulated its members with a "convincing victory'' [30], despite the evidence of fraud covered in the local press and multiple crime reports under consideration by the police. Physical evidence — used security bags — seized by the police after V.M.'s crime report at precinct 217 were later destroyed as “waste material” without examination. By law, every polling station has round-the-clock indoor video surveillance filming the room and the safe. These recordings were stored at the Territorial election commission of Vlasikha town. All requests to view them had been declined and the recordings were eventually destroyed.

A lawsuit requesting that the elections be declared void and detailing all the available evidence (including this paper and A.P.'s expert report) was unsuccessful; the court declined to hear any witness or request procurement documents for the security bags. Its decision simply stated that "no evidence of significant irregularities was presented''. The appellate court upheld that decision, declining all motions to call witnesses, request documents, and examine parts of the original bags available, and ruling that statistical inferences and all the images used in this study are inadmissible as evidence. The cassation and Supreme courts upheld the decision.

The data collected by us indicates that two large batches of bags with overlapping number ranges were made for the Election commission of Moscow Region, which then distributed pairs of identical bags to Vlasikha (appendix D10). The courts declined all motions to investigate this further. The Election commission of Moscow Region and the bag manufacturer (Aceplomb Technology located near St. Petersburg [2]) both declined to provide written comments. The latter has been supplying security bags to election commissions nationwide since the introduction of multi-day voting in 2020 [45]. Our complaint to the Central election commission regarding inadequate ballot storage procedures, with a proposal to improve them, was dismissed [27].

The authors — and more than twenty people who have contributed to this study — find it difficult to imagine what motivation and logic drive numerous election officials, all recruited from the local population, to be complicit in stealing votes from their own neighbours. This study also illustrates the extent of corruption and decay of political rights in Russia, even at the most local level of society.

Acknowledgments. We thank Vladimir Zaitsev for campaign coordination and support. We thank all 14 candidates nominated by CP, 5 additional observers, and 2 commission members for collecting the evidence and transcribing the vote counts. We thank Andrey Brazhnikov for discussions.

Author contributions. A.P. performed the statistical analysis. V.M. coordinated the collection of evidence and its analysis. Both authors wrote the paper.

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availability. Video recordings, photographs, and copies of documents are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Received 08.06.2025. revision received 02.09.2025.

Appendix A: Transcripts of vote counting

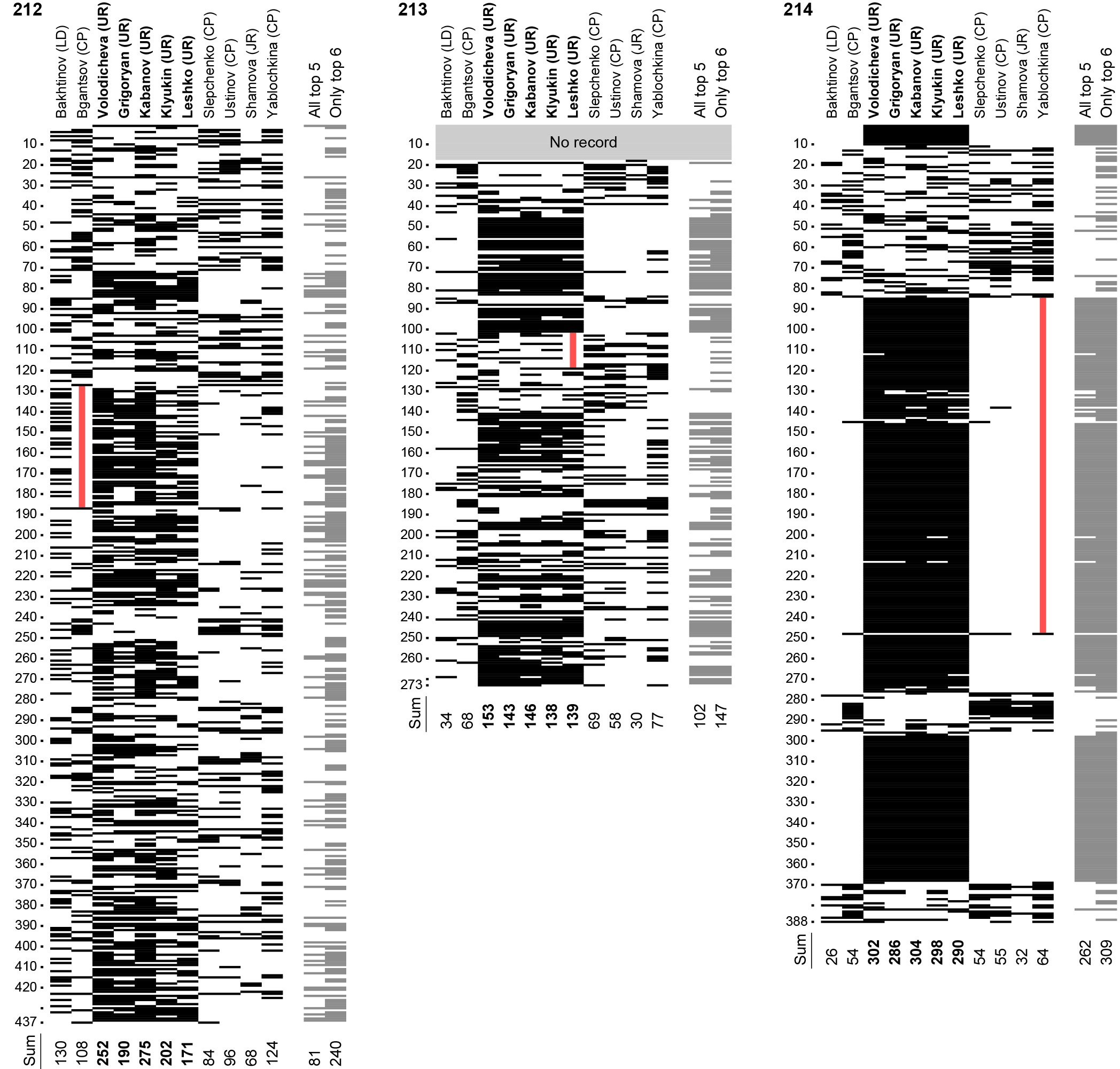

The transcripts for all 9 physical precincts are shown in fig. 3–5. Ballot ranges in the transcripts that lie outside continuous sequences of identical or almost-identical ballots for the 5 pro-administration candidates clearly show the voters' preference for the opposition candidates. In precinct 214 (fig. 3), except the 3 packs for the candidates nominated by UR, most of the remaining seemingly random votes are for the 4 CP's nominees and one UR's nominee. As discussed in main text, in the honest precinct 215 (fig. 4), the voter's preferences are for 4 CP's nominees and one UR's nominee. In precincts 219 and 220 (fig. 5), after we exclude the continuous sequences for the pro-administration candidates, the remaining random-looking votes are clearly in favor of the 5 CP's nominees. In precinct 219, the commission did not mix or rearrange the ballots at all, allowing us to trace the origin of every ballot in the transcript. Ballots 96 through 221 come from the first-day bag that was swapped. These ballots contain a few random votes (probably introduced intentionally in an attempt to mask the fraud) but nevertheless no votes for the popular candidate Razina (CP), forming an extremely improbable sequence (resulting in \(\alpha' = 2.2 \times 10^{-19}\)).

Fig. 3. Transcript of vote counting for precincts 212, 213, and 214 of electoral district 1. Top 5 candidates at each precinct are shown in bold. The least probable series is denoted by a red (grey) line. The last two grey columns are consolidated flags (appendix B3). Number of absentee voters per precinct is 4, 17, 0. At precinct 213, our recording starts late and misses about 17 first ballots. Only the recorded 256 ballots are thus used in our calculations.

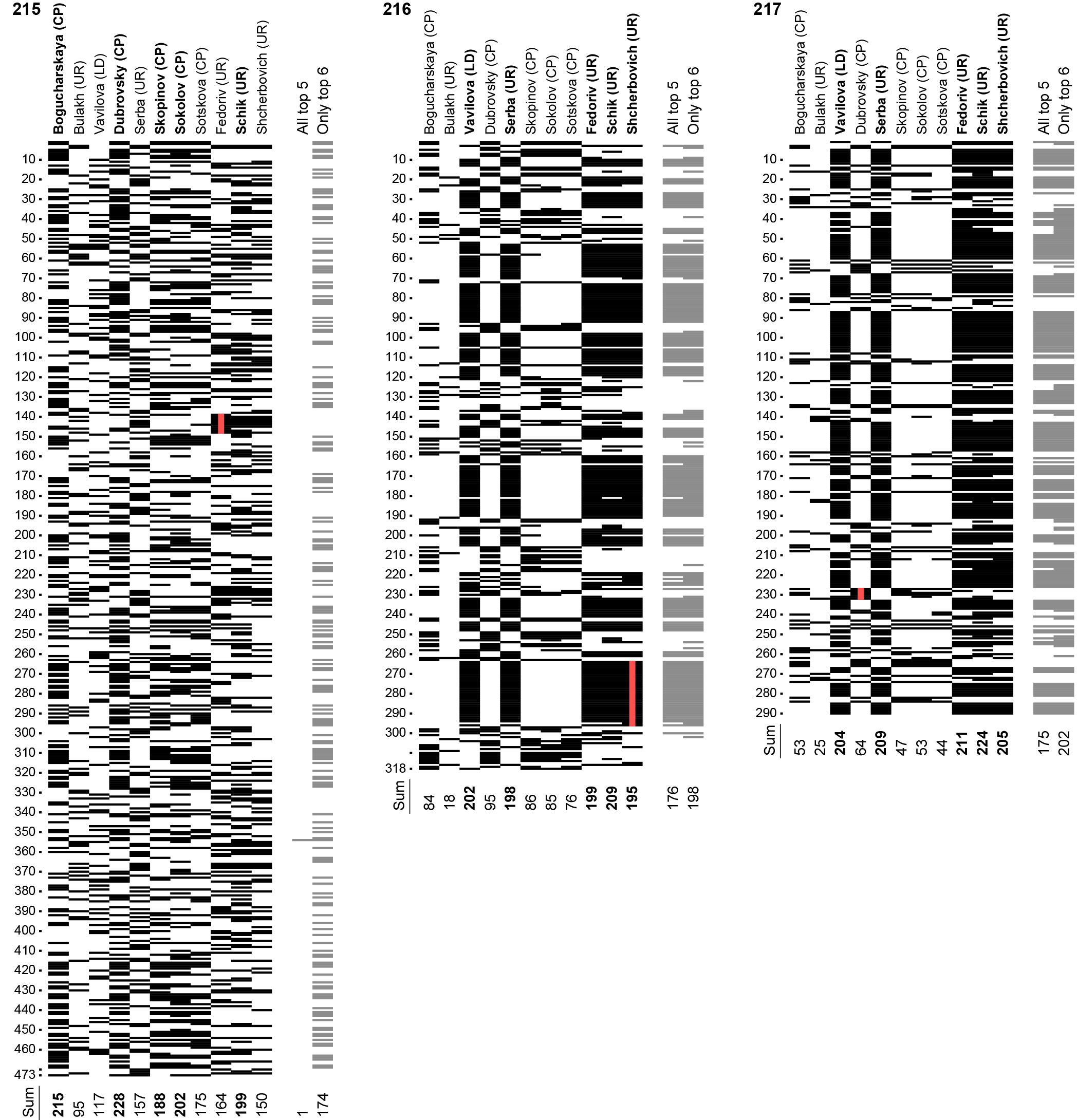

Fig. 4. Transcript of vote counting for precincts 215, 216, and 217 of electoral district 2. Top 5 candidates at each precinct are shown in bold. The least probable series is denoted by a red (grey) line. The last two grey columns are consolidated flags (appendix B3). Number of absentee voters per precinct is 4, 6, 9.

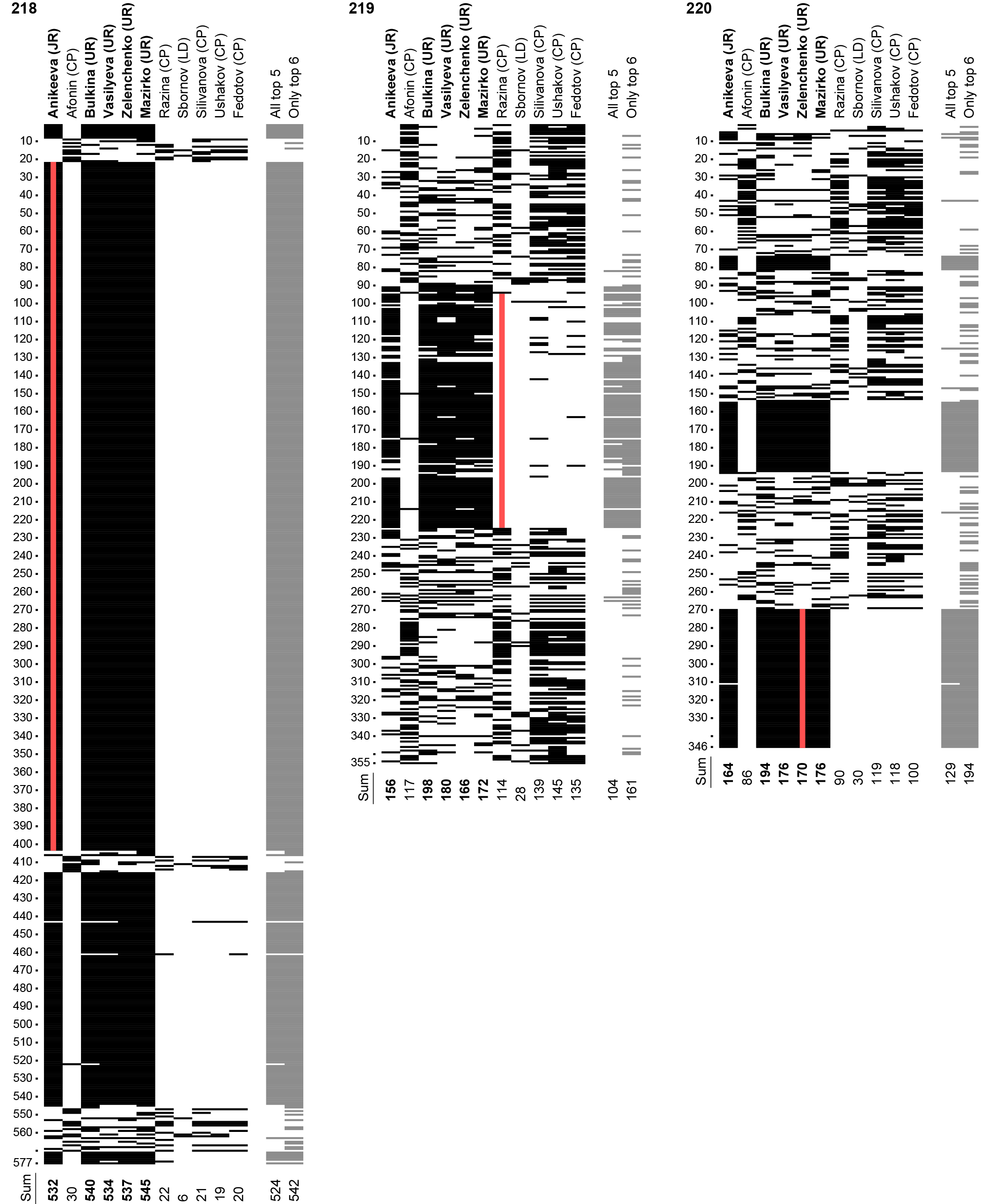

Fig. 5. Transcript of vote counting for precincts 218, 219, and 220 of electoral district 3. Top 5 candidates at each precinct are shown in bold. The least probable series is denoted by a red (grey) line. The last two grey columns are consolidated flags (appendix B3). Number of absentee voters per precinct is 0, 22, 1.

In electoral district 2 (fig. 4), the transcripts display another notable discrepancy. Precinct 215 has only 6 ballots with marks for all 5 candidates who got the council seats (Vavilova nominated by LD and 4 nominated by UR: Serba, Fedoriv, Schik, Scherbovich). This set of candidates is unlikely to be chosen by a real voter with genuine pro-administration political preferences, because the voter would have to ignore the fifth UR's candidate Bulakh in favour of Vavilova nominated by another party. Indeed, 38 voters in this precinct marked all 5 UR candidates, including Bulakh. However, in precincts 216 and 217, there are 176 and 175 ballots for all 5 candidates who got the council seats, just a few ballots fewer than the tampered-with security bags contain. Likewise, in precinct 219 (fig. 5), 94 out of 104 ballots with 5 marks for the unlikely set of candidates who got the council seats (Anikeeva nominated by JR and the 4 nominated by UR) fall within the range traced to the swapped bag. To be fair to UR, in district 3 they unexpectedly lost their fifth nominee who withdrew from the race days before the voting, after it became public that he had failed to declare his previous criminal conviction.

A few paper ballots were cast by absentee voters who, for medical and other reasons, could not come to the polling station and requested the commission members to visit them at home with a portable ballot box. The number of such voters is low, between 0 and 22 per precinct, and does not significantly affect the results.

Appendix B: Calculation of significances

The subject of our analysis is the sequence of valid ballots. They are considered in the order they are retrieved from the ballot box and announced when the votes are being tallied. Invalid ballots are excluded from consideration.

Let \(n\) be the number of valid ballots at the precinct. For each candidate running in that precinct, the sequence of ballots is converted into a sequence of flags \(f\in\left\{0;1\right\}\). Zero means that the candidate was not marked by the voter who filled the ballot, and one means that he or she was.

Let some candidate have a total of \(r_0\) zeros and \(r_1\) ones (\(r_0+r_1=n\)). The fraction of voters supporting this candidate is \(p_1=q_0=r_1/n\) and the fraction of voters not supporting him or she is \(p_0=q_1=r_0/n\). These fractions are treated as the probabilities of the occurrence of ones and zeros in the flag sequence, with the normalisation \(p_f+q_f=1\). Successive ballots are considered to be mutually independent.

1. Probability of a long series of flags

Let the longest continuous series of zeros and ones for a candidate have the length of \(s_0\) and \(s_1\) flags. If the probability \(p_f\) of occurrence of the flag \(f\) happens to be not large enough to explain the length of the series \(s_f\), one can suspect falsification of voting results by stuffing a bunch of ballots not filled out by voters. All the ballots in such a batch are most likely filled out identically, while the will of each real voter is individual, so each of them can easily break the series.

Suspicions of fraud can be verified using mathematical statistics. Let us formulate a null-hypothesis that long continuous series of flags arose naturally by chance. An alternative hypothesis is that there was some tampering leading to the emergence of the long series. The choice between these two hypotheses is based on a statistical significance of the null-hypothesis \(\alpha\). It quantifies the risk of so-called type I error. That means \(\alpha\) is the probability of mistakenly rejecting the null-hypothesis being true. In other words, if the significance of the null-hypothesis turns out to be small, this means that the fraud took place. The opposite is generally not true: if the significance is large, we cannot reasonably assert anything about the presence or absence of the fraud.

The algorithm for precisely calculating the significance for the longest series of flags is quite complex. Therefore, let us first upper-bound \(\alpha\) in a simple way. For this, we assume only one series of flags \(f\) of length at least \(s_f\) to be present. This assumption is precise only for a sufficiently long series, while for short ones it leads to an overestimation of \(\alpha_f\), because short series may appear multiple times in the sequence and each series is taken into account as many times as it appears. This approach is acceptable because it only weakens the statistical test.

Under the assumption made, the probability of observing a series of length at least \(s\) and starting with the very first flag is \(p^s\) (we omit the index \(f\) hereafter). The probability of observing such a series starting with any of the subsequent \(n-s\) flags is \(q p^s\), because the flag preceding the series must differ from the flags in it. The instances of the series starting with different flag positions are incompatible. That allows us to sum their probabilities. Thus, the significance of the hypothesis about the natural occurrence of the series \(\alpha\leq[1+q(n-s)] p^s\). This simple formula can be used for quick estimates. A comparison with results of the exact calculation described below shows that this formula for the data under consideration overestimates \(\alpha\) by no more than \(5\%\) if \(\alpha<10^{-1}\). But the overestimation rises rapidly for greater \(\alpha\).

The exact calculation requires some more effort. Let \(u_{n,i,j}\) denote the probability that, in a sequence of \(n\) flags, the longest series of flags \(f\) has a length of exactly \(i\) ballots \((0\leq i\leq n)\), provided that exactly \(j\) \((0\leq j\leq i)\) last flags have the same state \(f\) as the flags of the series. These probabilities can be found using an iterative process corresponding to adding one more flag to the sequence (i.e., announcing the next ballot): \begin{equation*} u_{n+1,i,j}=\begin{cases}p (u_{n,i,j-1}+u_{n,i-1,j-1}) & \mbox{if } j=i \\ p u_{n,i,j-1} & \mbox{if } 0 \lt j \lt i \\ q w_{n,i} & \mbox{if } j=0 \end{cases}, \end{equation*} where \(w_{n,i}=\sum_{j=0}^{i}{u_{n,i,j}}\) is the unconditional probability that the longest series of flags \(f\) has a length of exactly \(s\). The normalisation \(u_{0,0,0}=1\) here is the initial condition and the constraints \(u_{n,n+1,j}=0\) and \(w_{n,n+1}=0\) are the boundary conditions.

When implemented on a computer, the algorithm can be simplified by using only a two-dimensional array for \(u\) and only a one-dimensional array for \(w\). New probability values obtained by increasing \(n\) are written over the old ones. In order to avoid referring to values that are not yet defined or have already been redefined, the arrays should be initialised to zeros, indices \(i\) and \(j\) should be iterated over in their decreasing order and the \(j\)-cycle should be nested in the \(i\)-cycle.

The exact probability that the longest series has a length of at least \(s\) is \(\alpha=\sum_{i=s}^{n}{w_{n,i}}\). Tables 2–4 show input data and results of this calculation for every candidate in every precinct (see the first 6 columns of every precinct).

In the calculation results, we observe a paradoxical effect of presumably genuine flag series identified as anomalous by the test. The point is that falsifications shift the estimates of the probabilities \(p\) and \(q\) from their true values. Relatively long series of votes cast for opposition candidates or against pro-administrative candidates may arise given the true probabilities of such an expression of the will of the voters. But these series already become improbable with the shifted probability estimates. At the same time, we note that the significances for such series are still not as small as for series of votes for pro-administration and against opposition candidates.

An event with probability \(1/t\) occurs on average once in \(t\) independent trials (more precisely, for large \(t\) it does not occur at all among the trials with \(1/e \approx 36.8\%\) probability, occurs exactly once with \(1/e \approx 36.8\%\), twice with \(1/2e \approx 18.4\%\), and three or more times with \(1-2.5/e \approx 8.0\%\) probability). There are \(c=11\) candidates for each of \(9\) precincts under consideration and \(2\) possible flag values. So \(t=11 \times 9 \times 2=198\). Therefore, only significances \(\alpha_f<1/198\) are suspicious. The powers of such values are shown in bold in the tables. Similarly, the powers of \(\alpha'<1/9\) are shown in bold in table 1, where the multiplicity of candidates and flag states is already taken into account.

It should be especially noted that suspicion is not yet proof. The appearance of one or even more suspicious significances is quite expected in each test. Suspicious values only require attention, while non-suspicious ones can be ignored.

The test does not reveal any candidates with suspicious \(\alpha_f\) for precincts 215 and 217 (table 3), it reveals 4 such candidates for precincts 212 and 213 (table 2), 9 for precinct 216 (table 3), and 10 or 11 for precincts 214 (table 2), 218, 219, and 220 (table 4). Moreover, for the last 4 precincts \(\alpha_{\min}<10^{-11}\), i.e., their probability of the absence of fraud is extremely low.

The low significance of the hypothesis regarding the natural occurrence of the data anomaly clearly indicates that tampering of the type being tested for took place. However, a high significance may mean either that no tampering occurred or that there was interference of a different type. In the context of the present analysis, such interference may, in particular, be the additional mixing of ballots before they are tallied (table 1). The mixing is neither required by law nor is a violation, but it makes detecting the ballot stuffing difficult. Therefore, it raises suspicion.

2. Probability of the number of series

When the ballots are partially mixed, they will no longer form a long continuous series even in a hypothetically stuffed batch. However, if the mixing is not thorough, unbroken fragments of this batch will remain. Due to this, the number of series \(m\) of consecutive flags with the same state will be lower than it would be in a normal situation. We thus calculate the probability of the occurrence of a certain number of series in the sequence of mutually independent ballots.

Let \(a_{n,i}\) and \(b_{n,i}\) be the probabilities that a sequence of \(n\) flags contains \(i\) series, given that the last flag of the sequence has a certain state \(f\) or the opposite state \(1-f\), respectively (the choice of this states does not affect the final results, so the index \(f\) is omitted in calculations below). The probabilities are sequentially calculated using iterative equations \(a_{n+1,i}=p(a_{n,i}+b_{n,i-1})\) and \(b_{n+1,i}=q(b_{n,i}+a_{n,i-1})\) corresponding to the addition of the next flag to the sequence. If the new flag coincides with the last flag of the sequence, the number of series does not change, and if it differs, it increases by \(1\). The initial conditions are \(a_{1,1}=p\) and \(b_{1,1}=q\), the boundary conditions are \(a_{n,0}=b_{n,0}=a_{n,n+1}=b_{n,n+1}=0\).

The probability of finding exactly \(i\) series in a sequence of \(n\) ballots is \(v_{n,i}=a_{n,i}+b_{n,i}\). Thus, the significance of the hypothesis that the final number of series \(m\) turns out to be small for natural reasons is \(\tilde{\alpha}=\sum_{i=1}^{m}{v_{n,i}}\).

In a computer implementation of this algorithm, just as for the previous one, it is possible to reduce the dimension of the arrays used. To do this, one should initialise the arrays to zeros and iterate over the index \(i\) in its decreasing order.

We can also get an analytical estimation \(\tilde{\alpha}\approx\Phi(m+1/2; \mu_n, \sigma_n)\), where \(\Phi\) is the Gaussian distribution function. The addition of \(1/2\) in the first argument partially compensates for the difference between the sum of discrete probabilities giving the exact significance and the integral of the probability density giving its estimate. The expectation \(\mu_n\) and variance \(\sigma_n^2\) can be exactly calculated using generating function techniques. Let us denote \(g_n(z)=\sum_{i}{a_{n,i}z^i}\), \(h_n(z)=\sum_{i}{b_{n,i}z^i}\), and \(y_n(z)=g_n(z)+h_n(z)=\sum_{i}{v_{n,i}z^i}\). Then the iterative equations take the form \(g_{n+1}=p (g_n+zh_n)\) and \(h_{n+1}=q (h_n+zg_n)\). They allow us to express the distribution parameters through the derivatives of the generating functions \(\mu_n=y'_n(1)=1+(n-1)\theta\) and, for \(n>1\), \(\sigma_n^2=y''_n(1)+\mu_n-\mu_n^2=(2n-3)\theta-(3n-5)\theta^2\), where \(\theta=2pq\) is the average toggle frequency between series. The intermediate calculations here are quite cumbersome, so we skip them.

This approximation has a considerable drawback when compared with the estimate for the first test. Here, the significance can not only be overestimated (which is acceptable), but also underestimated (which is highly undesirable). Therefore, approximate values of \(\tilde{\alpha}\) should be treated with caution. For the data under consideration, the greatest overestimation can reach several orders of magnitude (although it reaches at least \(1\) order only for \(\tilde{\alpha}<10^{-6}\)), while the greatest underestimation is less than \(6\%\) for \(\tilde{\alpha}<10^{-1}\).

Tables 2–4 show the results of exact calculations for each candidate in every precinct (see the third- and second-to-last columns for each precinct).

Table 2. Calculation results for precincts of electoral district 1

| Candidate (nominee of) | Precinct 212 | Precinct 213 | Precinct 214 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) | \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) | \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) | |

| Bakhtinov (LD) | 307 | 16 | 0.4 | 130 | 4 | 0.0 | 197 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 222 | 29 | 0.4 | 34 | 3 | 0.4 | 59 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 362 | 194 | 4.7 | 26 | 2 | 0.1 | 38 | 1.0 | 5.5 |

| Bgantsov (CP) | 329 | 59 | 5.3 | 108 | 5 | 0.6 | 138 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 188 | 32 | 2.5 | 68 | 5 | 0.7 | 83 | 1.5 | 4.2 | 334 | 102 | 5.0 | 54 | 8 | 4.3 | 60 | 3.1 | 13.4 |

| Volodicheva (UR) | 185 | 9 | 1.0 | 252 | 12 | 0.7 | 184 | 2.5 | 4.9 | 103 | 10 | 1.8 | 153 | 20 | 2.5 | 92 | 4.1 | 5.6 | 86 | 10 | 4.1 | 302 | 72 | 6.0 | 55 | 12.6 | 21.2 |

| Grigoryan (UR) | 247 | 12 | 0.7 | 190 | 9 | 0.9 | 168 | 5.3 | 2.9 | 113 | 12 | 2.1 | 143 | 16 | 2.0 | 90 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 102 | 19 | 8.6 | 286 | 71 | 7.5 | 52 | 19.4 | 24.7 |

| Kabanov (UR) | 162 | 11 | 2.3 | 275 | 14 | 0.7 | 156 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 110 | 10 | 1.5 | 146 | 14 | 1.4 | 92 | 4.7 | 7.2 | 84 | 13 | 6.2 | 304 | 104 | 9.2 | 54 | 12.5 | 21.8 |

| Klyukin (UR) | 235 | 11 | 0.7 | 202 | 9 | 0.7 | 188 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 118 | 10 | 1.2 | 138 | 11 | 0.9 | 91 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 90 | 15 | 7.1 | 298 | 72 | 6.4 | 62 | 11.9 | 19.5 |

| Leshko (UR) | 266 | 24 | 3.0 | 171 | 12 | 2.5 | 174 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 117 | 17 | 3.7 | 139 | 10 | 0.6 | 95 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 98 | 15 | 6.5 | 290 | 102 | 11.0 | 66 | 13.1 | 23.3 |

| Slepchenko (CP) | 353 | 35 | 1.4 | 84 | 4 | 0.4 | 116 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 187 | 32 | 2.6 | 69 | 4 | 0.2 | 90 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 334 | 102 | 5.0 | 54 | 7 | 3.5 | 65 | 2.4 | 11.5 |

| Ustinov (CP) | 341 | 56 | 4.1 | 96 | 7 | 2.1 | 117 | 2.5 | 4.8 | 198 | 32 | 1.9 | 58 | 4 | 0.4 | 81 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 333 | 109 | 5.6 | 55 | 9 | 5.1 | 54 | 4.4 | 10.6 |

| Shamova (JR) | 369 | 41 | 1.2 | 68 | 5 | 1.5 | 103 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 226 | 45 | 1.0 | 30 | 4 | 1.4 | 48 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 356 | 193 | 6.0 | 32 | 5 | 2.9 | 49 | 0.8 | 9.2 |

| Yablochkina (CP) | 313 | 16 | 0.4 | 124 | 4 | 0.1 | 159 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 179 | 22 | 1.6 | 77 | 8 | 1.9 | 82 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 324 | 163 | 11.2 | 64 | 9 | 4.5 | 60 | 5.3 | 16.3 |

Suspiciously high powers of significances are shown in bold (Appendix B1).

Table 3. Calculation results for precincts of electoral district 2

| Candidate (nominee of) | Precinct 215 | Precinct 216 | Precinct 217 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) | \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) | \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) | |

| Bogucharskaya (CP) | 258 | 14 | 1.4 | 215 | 7 | 0.2 | 217 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 234 | 34 | 2.6 | 84 | 6 | 1.1 | 93 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 237 | 26 | 0.6 | 53 | 4 | 0.6 | 77 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Bulakh (UR) | 378 | 22 | 0.3 | 95 | 3 | 0.0 | 149 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 300 | 62 | 0.4 | 18 | 1 | 0.0 | 37 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 265 | 31 | 0.1 | 25 | 3 | 0.8 | 43 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Vavilova (LD) | 356 | 14 | 0.0 | 117 | 4 | 0.1 | 185 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 116 | 13 | 3.4 | 202 | 31 | 4.1 | 76 | 13.8 | 7.7 | 86 | 6 | 0.9 | 204 | 21 | 1.3 | 89 | 3.4 | 2.4 |

| Dubrovskiy (CP) | 245 | 8 | 0.2 | 228 | 8 | 0.3 | 221 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 223 | 33 | 3.2 | 95 | 6 | 0.8 | 94 | 4.5 | 6.4 | 226 | 21 | 0.6 | 64 | 6 | 1.6 | 81 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| Serba (UR) | 316 | 14 | 0.4 | 157 | 4 | 0.0 | 194 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 120 | 9 | 1.5 | 198 | 31 | 4.3 | 83 | 12.2 | 8.1 | 81 | 6 | 1.0 | 209 | 21 | 1.1 | 83 | 3.7 | 1.4 |

| Skopinov (CP) | 285 | 11 | 0.3 | 188 | 7 | 0.4 | 208 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 232 | 33 | 2.6 | 86 | 5 | 0.5 | 85 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 243 | 28 | 0.6 | 47 | 4 | 0.8 | 69 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Sokolov (CP) | 271 | 9 | 0.1 | 202 | 7 | 0.3 | 209 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 233 | 33 | 2.6 | 85 | 5 | 0.6 | 81 | 5.1 | 6.5 | 237 | 28 | 0.8 | 53 | 5 | 1.3 | 71 | 1.3 | 0.2 |

| Sotskova (CP) | 298 | 16 | 1.0 | 175 | 6 | 0.3 | 183 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 242 | 33 | 2.1 | 76 | 6 | 1.4 | 85 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 246 | 28 | 0.5 | 44 | 4 | 0.9 | 73 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Fedoriv (UR) | 309 | 10 | 0.0 | 164 | 10 | 2.1 | 193 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 119 | 13 | 3.3 | 199 | 31 | 4.3 | 65 | 18.9 | 8.7 | 79 | 5 | 0.6 | 211 | 21 | 1.0 | 87 | 2.7 | 1.0 |

| Shik (UR) | 274 | 9 | 0.1 | 199 | 6 | 0.1 | 221 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 109 | 11 | 2.8 | 209 | 31 | 3.7 | 91 | 7.6 | 6.2 | 66 | 5 | 0.9 | 224 | 21 | 0.6 | 89 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Shcherbovich (UR) | 323 | 13 | 0.2 | 150 | 6 | 0.6 | 203 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 123 | 13 | 3.1 | 195 | 33 | 5.0 | 61 | 22.0 | 10.2 | 85 | 4 | 0.1 | 205 | 21 | 1.3 | 89 | 3.3 | 1.8 |

Suspiciously high powers of significances are shown in bold (Appendix B1).

Table 4. Calculation results for precincts of electoral district 3

| Candidate (nominee of) | Precinct 218 | Precinct 219 | Precinct 220 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) | \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) | \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) | |

| Anikeeva (JR) | 45 | 13 | 11.7 | 532 | 382 | 12.3 | 19 | 10.4 | 26.0 | 199 | 30 | 5.4 | 156 | 32 | 9.2 | 85 | 21.2 | 26.5 | 182 | 21 | 3.7 | 164 | 41 | 11.1 | 70 | 29.4 | 25.1 |

| Afonin (CP) | 547 | 385 | 7.9 | 30 | 5 | 3.7 | 31 | 2.6 | 13.9 | 238 | 55 | 7.6 | 117 | 11 | 2.9 | 125 | 3.0 | 17.4 | 260 | 82 | 8.4 | 86 | 6 | 1.2 | 92 | 3.7 | 12.7 |

| Bulkina (UR) | 37 | 5 | 3.2 | 540 | 383 | 9.9 | 31 | 4.4 | 17.3 | 157 | 10 | 1.3 | 198 | 47 | 9.8 | 114 | 10.3 | 20.5 | 152 | 10 | 1.3 | 194 | 78 | 17.5 | 94 | 15.9 | 20.6 |

| Vasilyeva (UR) | 43 | 8 | 6.3 | 534 | 383 | 11.7 | 29 | 6.6 | 26.9 | 175 | 26 | 5.8 | 180 | 29 | 6.3 | 99 | 17.0 | 24.8 | 170 | 13 | 1.8 | 176 | 77 | 20.5 | 86 | 21.3 | 22.0 |

| Zelenchenko (UR) | 40 | 11 | 10.0 | 537 | 382 | 10.8 | 25 | 6.7 | 25.0 | 189 | 26 | 4.9 | 166 | 42 | 11.6 | 89 | 20.9 | 29.6 | 176 | 18 | 3.1 | 170 | 77 | 21.6 | 68 | 31.2 | 25.3 |

| Mazirko (UR) | 32 | 5 | 3.5 | 545 | 385 | 8.5 | 27 | 3.8 | 18.3 | 183 | 13 | 1.5 | 172 | 35 | 8.8 | 101 | 16.0 | 22.5 | 170 | 17 | 3.0 | 176 | 77 | 20.5 | 82 | 23.3 | 26.7 |

| Razina (CP) | 555 | 386 | 5.6 | 22 | 3 | 1.5 | 35 | 0.7 | 11.0 | 241 | 130 | 20.0 | 114 | 8 | 1.6 | 104 | 6.4 | 17.0 | 256 | 77 | 8.2 | 90 | 6 | 1.1 | 101 | 2.9 | 9.0 |

| Sbornov (LD) | 571 | 392 | 1.3 | 6 | 2 | 1.2 | 11 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 327 | 134 | 3.5 | 28 | 4 | 1.9 | 47 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 316 | 84 | 1.9 | 30 | 2 | 0.0 | 53 | 0.4 | 1.3 |

| Silivanova (CP) | 556 | 385 | 5.3 | 21 | 3 | 1.6 | 31 | 0.9 | 9.9 | 216 | 32 | 4.8 | 139 | 14 | 3.4 | 115 | 7.8 | 13.8 | 227 | 77 | 12.1 | 119 | 8 | 1.4 | 107 | 6.3 | 13.5 |

| Ushakov (CP) | 558 | 386 | 4.8 | 19 | 3 | 1.7 | 27 | 0.9 | 7.4 | 210 | 96 | 19.9 | 145 | 12 | 2.4 | 107 | 10.9 | 24.5 | 228 | 77 | 12.0 | 118 | 13 | 3.7 | 105 | 6.6 | 16.1 |

| Fedotov (CP) | 557 | 386 | 5.0 | 20 | 3 | 1.6 | 27 | 1.1 | 6.2 | 220 | 40 | 6.2 | 135 | 7 | 0.7 | 119 | 6.3 | 18.1 | 246 | 77 | 9.5 | 100 | 8 | 1.9 | 109 | 3.1 | 13.8 |

Suspiciously high powers of significances are shown in bold (Appendix B1).

Unlike the previous test, only one significance is calculated here, so \(t=11 \times 9=99\). Therefore, significances \(\tilde{\alpha}<1/99\) become suspicious. The similar condition \(\tilde{\alpha}'<1/9\) remains unchanged for the overall significance in table 1.

The qualitative results of both tests are generally consistent for every precinct except 216. The first test leaves some doubt in this precinct, while the second one succeeds in proving the fraud, despite the intentional mixing of ballots by the commission (table 1). This illustrates that the second test is useful. Moreover, the second test is robust to minor human errors in the transcript, whereas the first test is robust only as long as such errors do not affect the least probable series.

However, there is a certain problem with the second test. It gives \(\tilde{\alpha}_{\min} = 7.5 \times 10^{-4}\) in precinct 215, which most likely had no fraud. Of course, such significance could also be the result of an unfortunate combination of circumstances, especially since it is observed only for 1 candidate (for comparison, comparable suspicious values of \(\tilde{\alpha}\) for precinct 217 are observed for 4 candidates). Another possible explanation is that the successive ballots are not, in fact, absolutely independent. Perhaps they are not completely mixed for simultaneously voting voters. If this is true, then the second test turns out to be more sensitive to inaccuracies of our initial assumptions.

3. Consolidated tests over groups of candidates

To mitigate the hypothetical effect noted above, the source data for statistical tests are consolidated so as to analyse the sequence of flags not for each candidate individually, but for their entire list as a whole. The state of each flag is now determined by the voter's attitude towards the 5 candidates leading in the precinct. If the voter supported all of them, \(f=1\), and in any other case, \(f=0\) (as visualised in the second-last grey column of each precinct in fig. 3–5). All calculations are performed in the same way as before and the results are shown in table 5. Suspicious values for \(t = 9 \times 2 = 18\) independent trials for \(\alpha_f\) and \(t = 9\) independent trials for \(\tilde{\alpha}\) and \(\breve{\alpha}\) (see below) are shown in bold.

Table 5. Calculation results for the consolidated tests

| Precinct | \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) |

| 212 | 356 | 24 | 0.4 | 81 | 4 | 0.5 | 126 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| 213 | 154 | 27 | 4.0 | 102 | 10 | 1.8 | 81 | 6.6 | 7.2 |

| 214 | 126 | 34 | 14.2 | 262 | 71 | 10.1 | 36 | 37.6 | 30.3 |

| 215 | 472 | 353 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| 216 | 142 | 19 | 4.4 | 176 | 31 | 5.9 | 57 | 29.9 | 12.7 |

| 217 | 115 | 11 | 2.2 | 175 | 21 | 2.6 | 71 | 14.2 | 3.6 |

| 218 | 53 | 18 | 16.0 | 524 | 382 | 14.7 | 19 | 13.4 | 32.8 |

| 219 | 251 | 90 | 11.7 | 104 | 17 | 6.7 | 45 | 23.0 | 35.4 |

| 220 | 217 | 53 | 8.7 | 129 | 41 | 15.3 | 20 | 51.0 | 39.7 |

Suspiciously high powers of significances are shown in bold (Appendix B1).

The consolidated tests not only resolves doubts in favour of precinct 215, but it also conclusively proves fraud at precinct 217. At the same time, precinct 212 somehow manages to avoid suspicion in the consolidated tests, which requires an explanation.

The problem here is the implicit assumption that falsifiers help only the winners and help them all. However, a more complex fraud scheme was apparently implemented at precinct 212. To understand this scheme, a certain degree of political-science analysis is required that goes somewhat beyond the realm of mathematical statistics.

LD nominee Bakhtinov is 6th most popular in precinct 212, while in precinct 213 and e-voting precinct he is 10th (second least popular), and in precinct 214 he is 11th (the least popular) [53]. It should be clarified that LD party is quite unpopular in European Russia, so it nominated only 1 candidate in every electoral district of Vlasikha town. In district 3, LD nominee Sbornov is 11th (the least popular) in every precinct including e-voting, as he had no support from either voters or falsifiers. In district 2, LD nominee Vavilova is 10th (second least popular) in the honest precinct 215 and in e-voting, but 2nd and 5th in precincts 216 and 217, where she was on the list of pro-administration candidates who benefited from the ballot replacement. It is noteworthy that UR nominee Bulakh, eventually not included in this list in district 2, was 11th (the least popular) in all the precincts, which hints at the real popularity of the most powerful party.

To sum up, it can be assumed that the LD nominee had support from the falsifiers at precinct 212 as well, despite not being among the pro-administration candidates. It should also be noted that voters allegedly supporting the LD nominee gave 64.4% of their remaining votes to the winning pro-administrative candidates at precinct 212. This value is lower, 38.9% (26.9%) at precinct 213 (214).

We can only guess how this happened. On the one hand, it may be a case of silent sabotage. If the falsifiers did not want to carry out their criminal duties, but were afraid to openly protest, they could mark the weakest of the candidates pretending to make a mistake. On the other hand, it could be an attempt to disguise the fraud without risking helping the opposition. Both of these situations seem quite exotic, which is why this phenomenon is rare and affects only one precinct.

None of the proposed explanations exclude the possibility of fewer than 5 candidates were marked on the falsified ballots. Taking this into account, the consolidated test is tuned up as follows. Now \(f=1\) if the ballot contains marks for any of the 6 most popular candidates in that precinct and no other marks, and \(f=0\) otherwise (as visualised in the last grey column of each precinct in 3–5). This allows us to detect fraud at precinct 212 with \(\tilde{\alpha}=6.2 \times 10^{-5}\). At the same time, for other precincts the significances \(\alpha_f\) and \(\tilde{\alpha}\) increase noticeably, but they still remain low enough to leave no doubt about fraud there (with the exception of precinct 215, of course; table 6).

Table 6. Calculation results for the tuned-up consolidated tests

| Precinct | \(r_0\) | \(s_0\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_0 \) | \(r_1\) | \(s_1\) | \(\textrm{p}\alpha_1 \) | \(m\) | \(\textrm{p}\tilde{\alpha}\) | \(\textrm{p}\breve{\alpha}\) |

| 212 | 197 | 9 | 0.8 | 240 | 15 | 1.6 | 176 | 4.2 | 3.9 |

| 213 | 109 | 10 | 1.6 | 147 | 15 | 1.6 | 99 | 3.2 | 4.7 |

| 214 | 79 | 10 | 4.4 | 309 | 102 | 8.3 | 62 | 8.7 | 20.3 |

| 215 | 299 | 14 | 0.6 | 174 | 6 | 0.3 | 208 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| 216 | 120 | 16 | 4.5 | 198 | 33 | 4.8 | 67 | 18.4 | 10.9 |

| 217 | 88 | 7 | 1.3 | 202 | 26 | 2.2 | 71 | 7.7 | 0.7 |

| 218 | 35 | 7 | 5.8 | 542 | 385 | 9.4 | 33 | 3.5 | 17.4 |

| 219 | 194 | 23 | 3.9 | 161 | 17 | 3.6 | 105 | 13.7 | 22.5 |

| 220 | 152 | 15 | 3.1 | 194 | 77 | 17.3 | 98 | 14.4 | 19.3 |

Suspiciously high powers of significances are shown in bold (Appendix B1).

The analysis above illustrates some important general considerations. Any rigorous formal test relies on an idea of how the fraud is carried out. Therefore, any such test can be passed with relatively little effort. However, falsifiers as a rule do not make this effort. On the one hand, they are usually confident in their complete impunity, and on the other hand, they are careless, like most people who commit crimes. This is precisely what allows us, in most cases, to propose effective statistical tests without using any political-science information. However, for a reliable analysis it is necessary to use the whole combination of available statistical tests, because the conditions of applicability of any single test may sometimes be violated.

4. Test for stationarity of vote flow

The analysis also contains another implicit assumption that probabilities of voting for a candidate are constant over time. But, for example, opposition voters may be more inclined to vote on the third day if they know their votes cast on the first two days might be stolen. In this case, the flow of votes becomes non-stationary. The constancy of probabilities can be verified as follows.

We split the sequence of flags into \(l\) segments of equal length (if \(n\) is not divisible by \(l\), then the boundary flags are distributed between adjacent segments in proportional shares). The number of ones \(k_i\) in a segment \(i=1, 2, ..., l\) is binomially distributed with an expectation \(\mu=r_1/l\) and variance \(\sigma^2=r_0r_1/nl\). This distribution can be approximated by a Gaussian distribution for a sufficiently large segment length \(n/l\). The statistics \(\sum_{i=1}^{l}{(k_i-\mu)^2/\sigma^2}\) has the \(\chi^2\)-distribution with \(l-1\) degrees of freedom (1 degree is spent on determining the distribution parameters). This allows us to calculate the significance \(\breve{\alpha}\) of the hypothesis that all deviations of the vote flow from the stationary one are random. The similar statistics for zeros with \(\mu=r_0/l\) is obviously the same.

The specific choice of \(l\) is not of major importance, although the presence of a free parameter is, in itself, a certain drawback of this approach. We use the value \(l=12\). This choice simultaneously provides several segments for each of the three voting days and ensures several dozen flags in each segment.

Tables 2–4 show the results of these calculations for each candidate in every precinct (see the last columns of every precinct). The probability of voting does not change over time for precinct 215 and perhaps for precinct 217. It changes noticeably for precincts 212 and 213 and very strongly at all the others. However, for the latter, one can no longer rely on the quantitative values of \(\breve{\alpha}\), since this asymptotic test tends to underestimate the significance increasingly as the value itself becomes smaller.

We have no doubt about the results of voting at precinct 215. So we can consider the assumption discussed to be valid for the voting in question. That also makes it possible to use the check of the stationarity of the vote flow as an auxiliary test, although it does not provide any new results compared to the two main tests. This test is less valuable as evidence, because the nonstationarity of the vote flow can in principle have natural causes. Although, of course, most often it is the result of fraud.

Similar results for the consolidated test are shown in the last column of table 5. The difference between the honest precinct 215 and precinct 217 with a good ballot mixing becomes here more noticeable. For precinct 212, with its unusual approach to falsification, the auxiliary test barely sees anomalies. But if we tune up the consolidation (table 6), we get \(\breve{\alpha}=1.2 \times 10^{-4}\) there, sufficient to have no doubt about the nonstationarity of the flag flow.

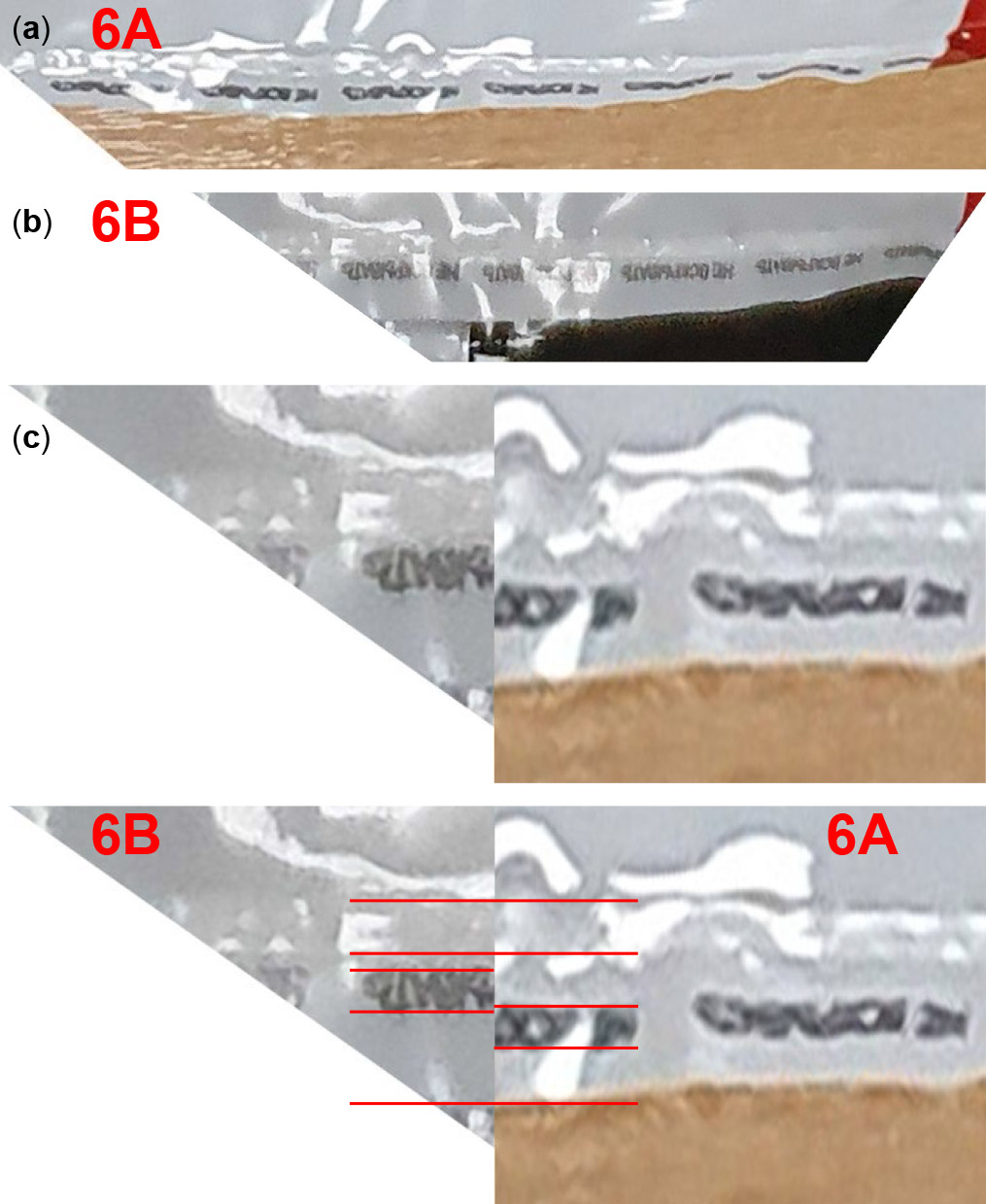

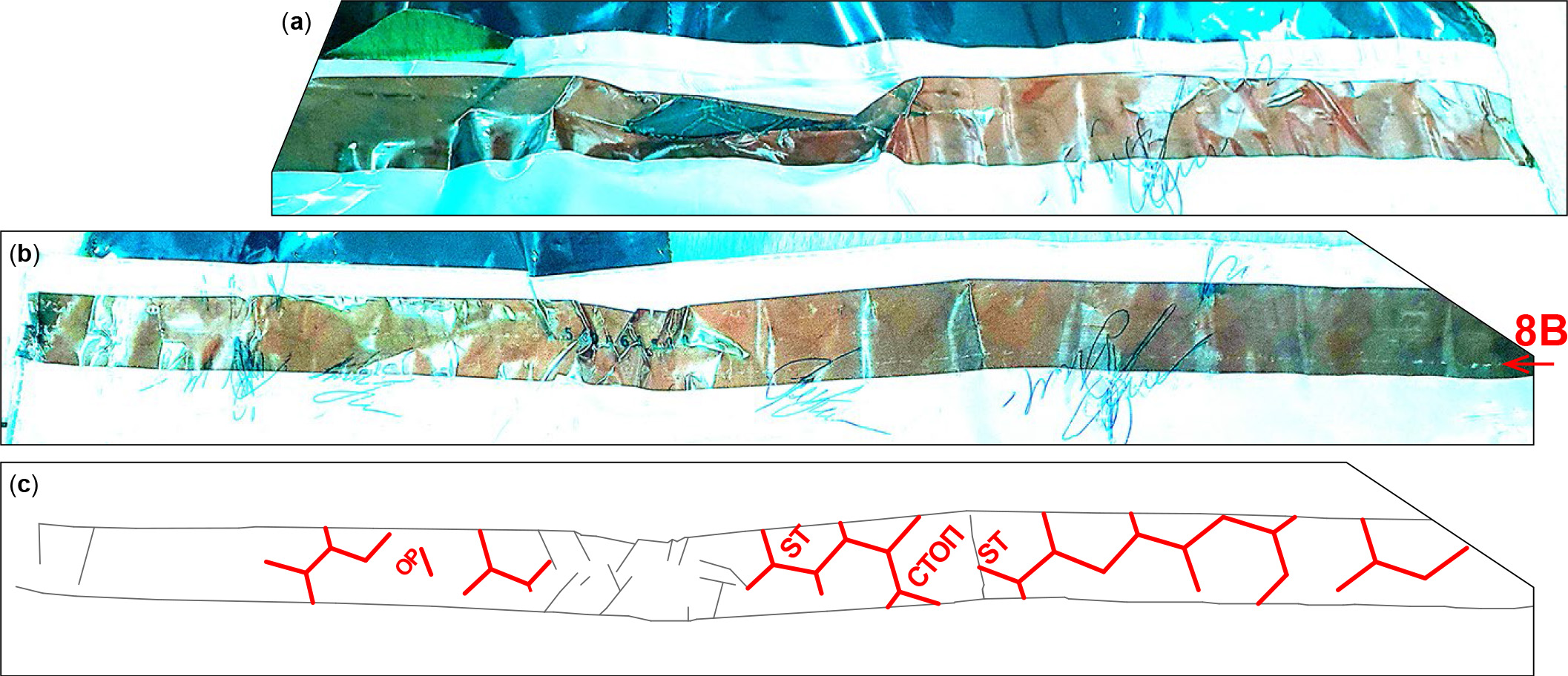

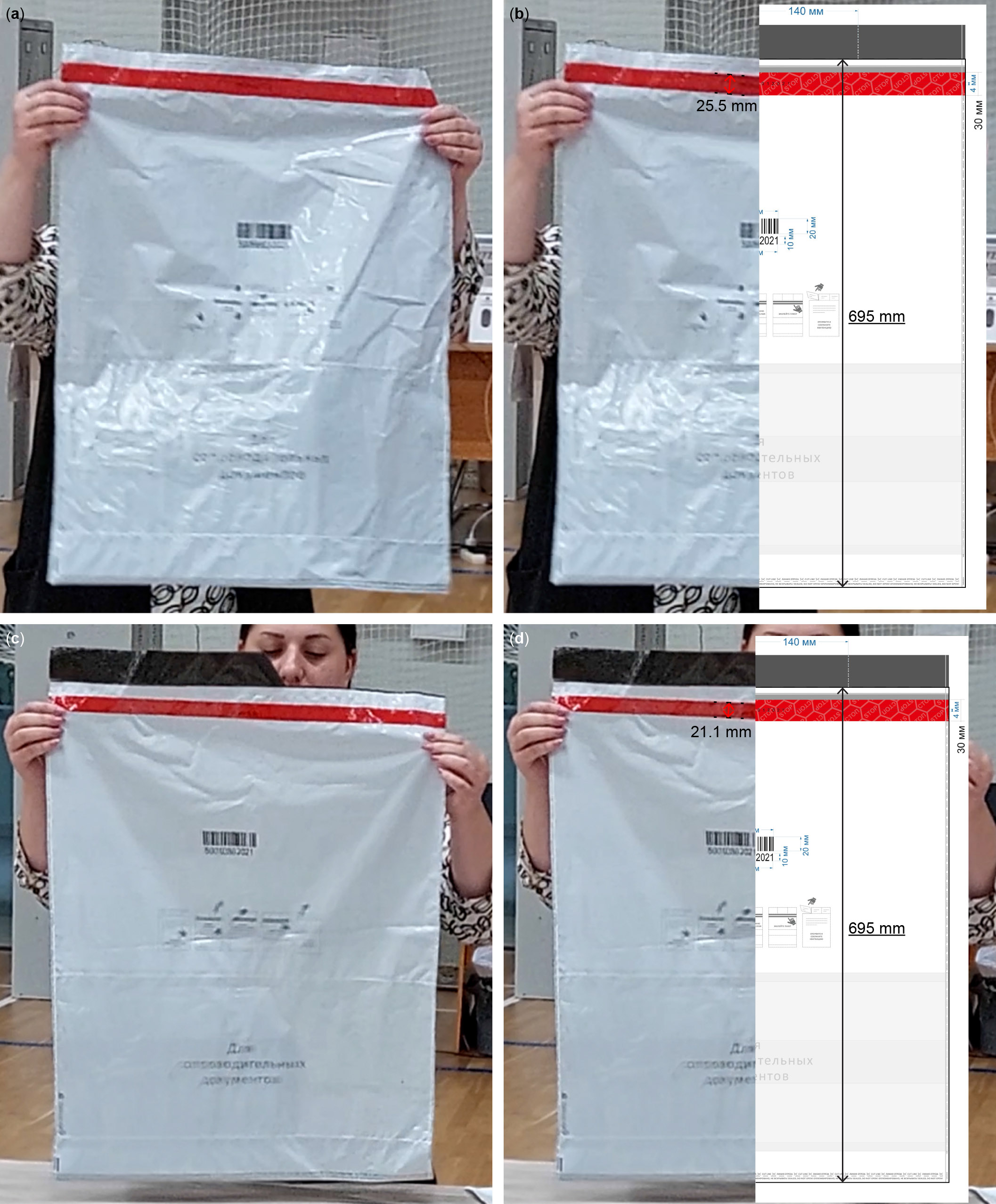

Appendix C: Circumventing tamper-indicating measures of security bags

Let us first review how the security bag is normally used. The red security tape initially adheres to the bag by its bottom edge, the rest of its glue-coated width being protected by a silicone-coated liner tape (fig. 6a). To seal the bag, the liner is removed and the red tape seals the bag opening (fig. 6b–d). An attempt to remove the tape tears its complex multi-layer glue structure apart, leaving visible traces (fig. 6e). If the tape is removed rapidly by brute force, the bag material stretches and may also tear. Note that the bag's unique number is printed on the adhesive layer of the security tape, thus it cannot be removed from the tape without leaving traces or replaced with a different number. The edges of the bag not protected by the tape have a small print running along them (also on the other side not photographed here), to make any attempt to open and reseal the edges visually evident, too [51]. The bag can be opened by cutting or tearing it apart at any place (fig. 6f).

Fig. 6. Normal use of the security bag. (a) In an unused bag, the security tape's bottom edge is already adhered permanently to the bag. A metallised liner protects the glue on its remaining unattached portion. A slice of the liner extends above the tape. The tape is transparent and the liner can be seen through it. (b) To seal the bag, the unattached portion of the tape with the liner is flipped over, so that its unattached adhesive portion faces up, without detaching the tape from the bag. The liner is then removed carefully, without fingers touching the adhesive being exposed. The tape is then flipped back over the bag opening, is pressed against the bag, and sticks to it permanently. (c) and (d) The security tape with the unique bag number seals the opening. The honeycomb pattern with words STOP СТОП is the outermost layer of its multi-layer adhesive. This pattern is made of light-grey adhesive and is clearly visible when the tape is not adhered to the bag or is covered by the reflective liner, but almost disappears once the adhesive attaches to the bag. (d) Control stubs can be detached from the bag. (e) An attempt to remove the security tape separates the multi-layer adhesive and reveals lettering within it. (f) The bag is normally opened by cutting it at the bottom.

The idea of a tamper-evident bag is that an attempt to access its content does not remain unnoticed. The faster this is discovered upon a visual inspection of the bag, the better. We present 5 possible methods to conceal the unauthorised access. Methods C1, C4 and C5 use readily available materials and do not require a collusion with the bag manufacturer. Methods C2 and C3 require access to duplicates of bags with identical numbers made at the factory. A diligent factory should not produce duplicate bags (as the bag numbers must be unique [12]. As discussed in appendix D, the evidence points that our election commissions have had access to such factory-made duplicates and used methods C2 and C3 to rig these particular elections.

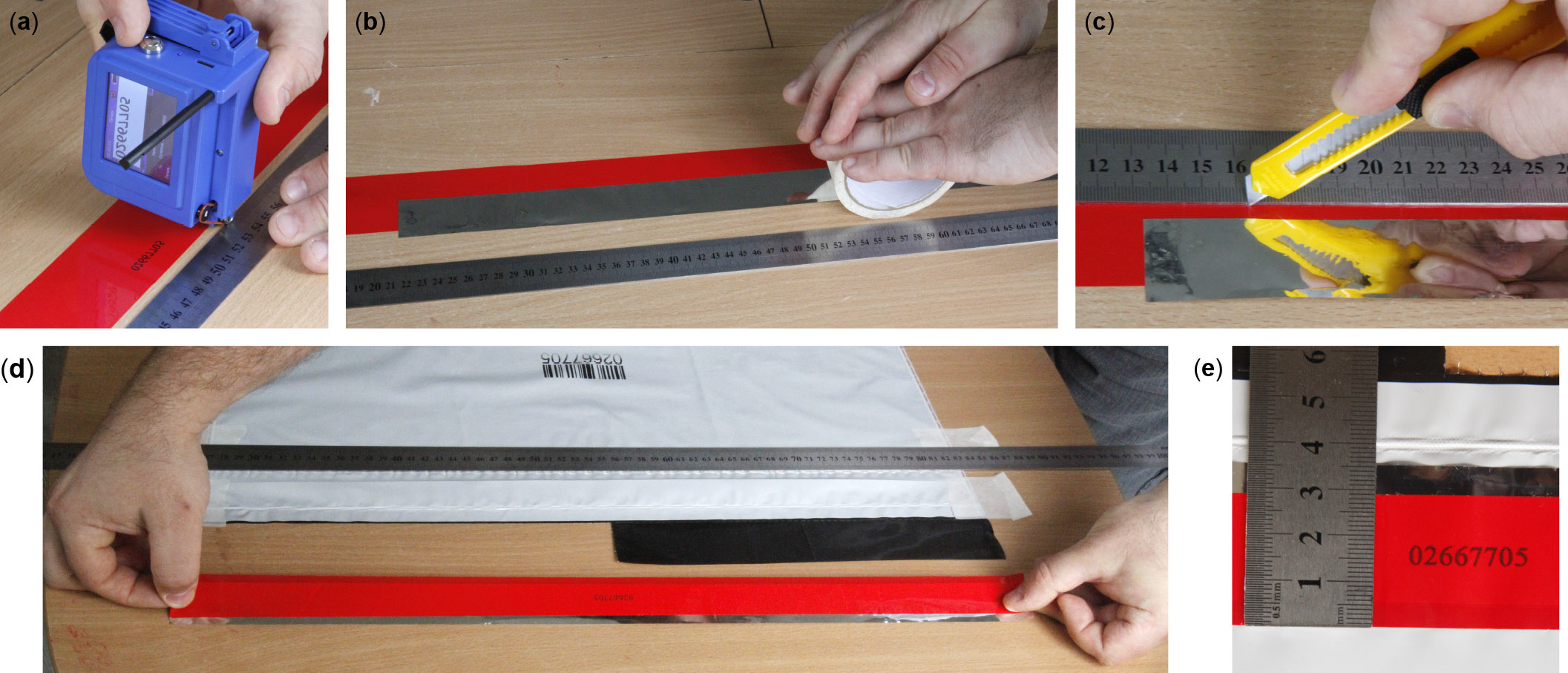

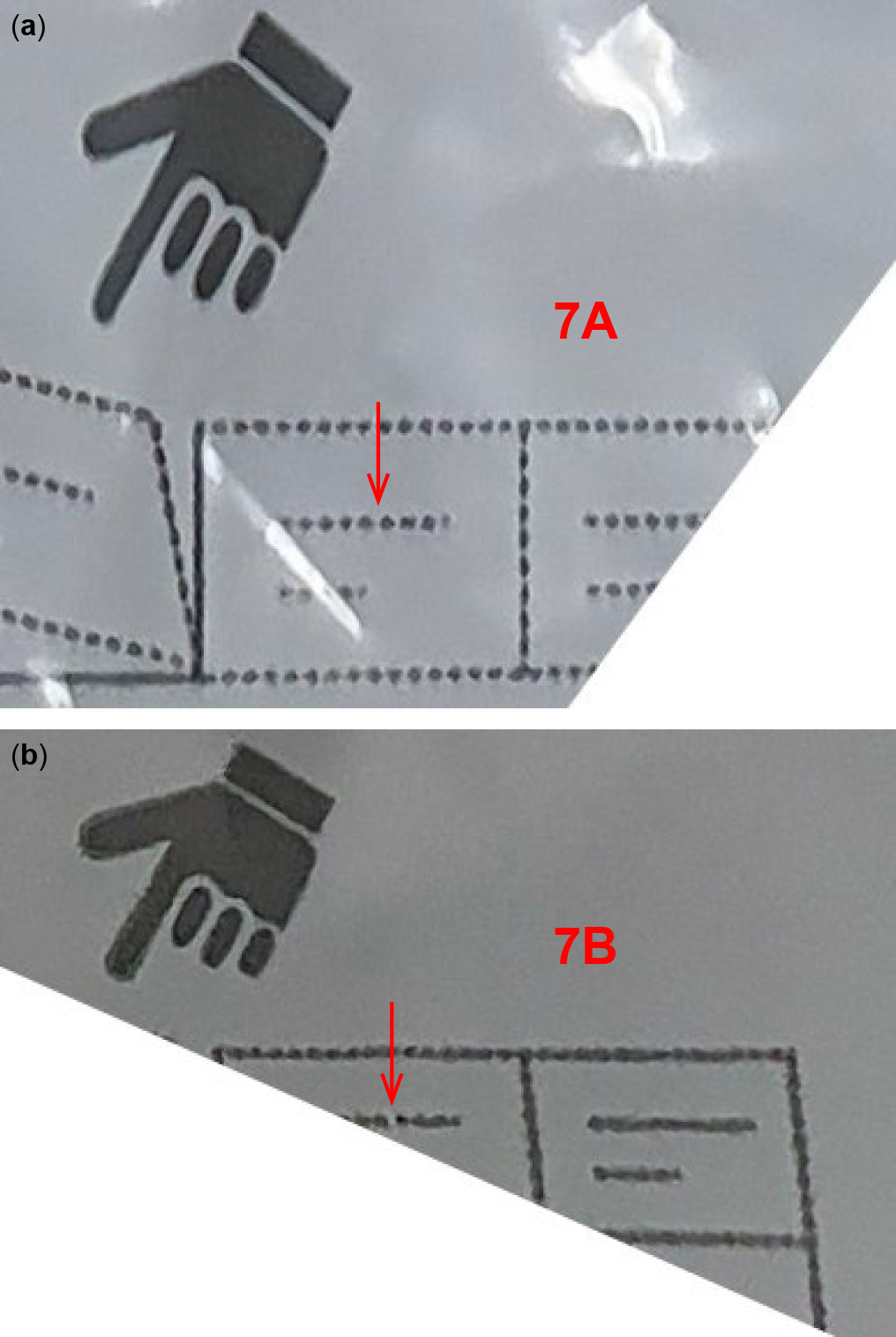

1. Imitation with red packing tape

Red-coloured packing tape mimics the visual appearance of the security tape in its sealed state (fig. 7), but not in the initial unsealed state. The latter difference can easily be overlooked, as most election observers are not familiar with the security bags.

Fig. 7. Red-coloured packing tape can mimic the visual appearance of the security tape in its sealed state. The left-hand side of each tape is fully adhered to the bag, while the right-hand side still has some liner under it. The topmost tape is original, while the other two are different brands of packing tape. The numbers on the latter were printed on their adhesive side with a handheld inkjet label printer. All three tapes are transparent and the red color is in their adhesive layer only.

Preparations proceed as follows. The original security tape is peeled off in advance, its used portion trimmed, and the remaining adhesive washed off the bag with a solvent (fig. 8). While the adhesive is resistant to many common solvents, we have found one that removes it easily without damaging the print along the bag's edges. The trimmed original tape is stored for future reuse.

Fig. 8. Removal of the original security tape from an unused bag. (a) The tape is peeled off carefully with the liner still attached, leaving a narrow strip of adhesive behind. (b) Tape is trimmed to remove the used portion of its width. (c) The trimmed original tape is less than 25 millimeters wide. (d) Adhesive residue is removed from the bag with solvent. (e) The bag is clean and undamaged.

A fake sealing tape is then made of suitable red-coloured packing tape (costs under $2). The bag's unique number is printed on its adhesive side with a handheld inkjet printer (costs around $100), which contactlessly marks any surface with fast-drying ink (fig. 9). A liner from another bag is applied to it. The tape is trimmed to correct size and installed on the bag.

Fig. 9. Installation of a fake tape. (a) A mirrored unique number is printed on the adhesive side of the packing tape. (b) Liner removed from another bag is attached to the tape. A round object is rolled over it to squeeze away bubbles. (c) The tape is trimmed to size. (d) The tape, cut to the size and with the liner attached, is installed on the bag. (e) The installed fake tape has the correct width of about 30 millimeters.

The modified bag is then used publicly to seal ballots in a normal way (fig. 10). At night, the fake tape is easily removed, the ballots are replaced, and the bag is resealed using the original stored tape (fig. 11). The ballots are then publicly retrieved from the bag that appears undamagedg (fig. 12). Should anyone try to peel the security tape off at this point, it would display the expected behavior. The only visual clue remaining is the reduced width of the tape, which is almost certain to be overlooked unless one knows specifically what to look for.

Fig. 10. Sealing ballots in the bag with the fake tape publicly. (a) Genuine ballots are placed inside the bag. (b) The liner is removed normally. (c) The bag is sealed with the tape normally.

Fig. 11. Opening the bag and replacing the ballots. (a) The fake tape is easily peeled off. If any of its adhesive remains on the bag, it can be removed with solvent. (b) The ballots are replaced with fraudulent ones. (c) The bag is sealed with the stored original tape. (d) The installed tape is however less than 25 millimeters wide, which is the only visible sign of the tampering. Its uneven bottom edge results from our slight inaccuracy when making this first sample; trimming it a millimeter narrower produces a perfect edge.

Fig. 12. The bag is opened publicly and the fraudulent ballots contained in it are counted as genuine.

Although this method is feasible, there is no evidence anyone has used it.

2. Swapping the bag for its factory-made duplicate

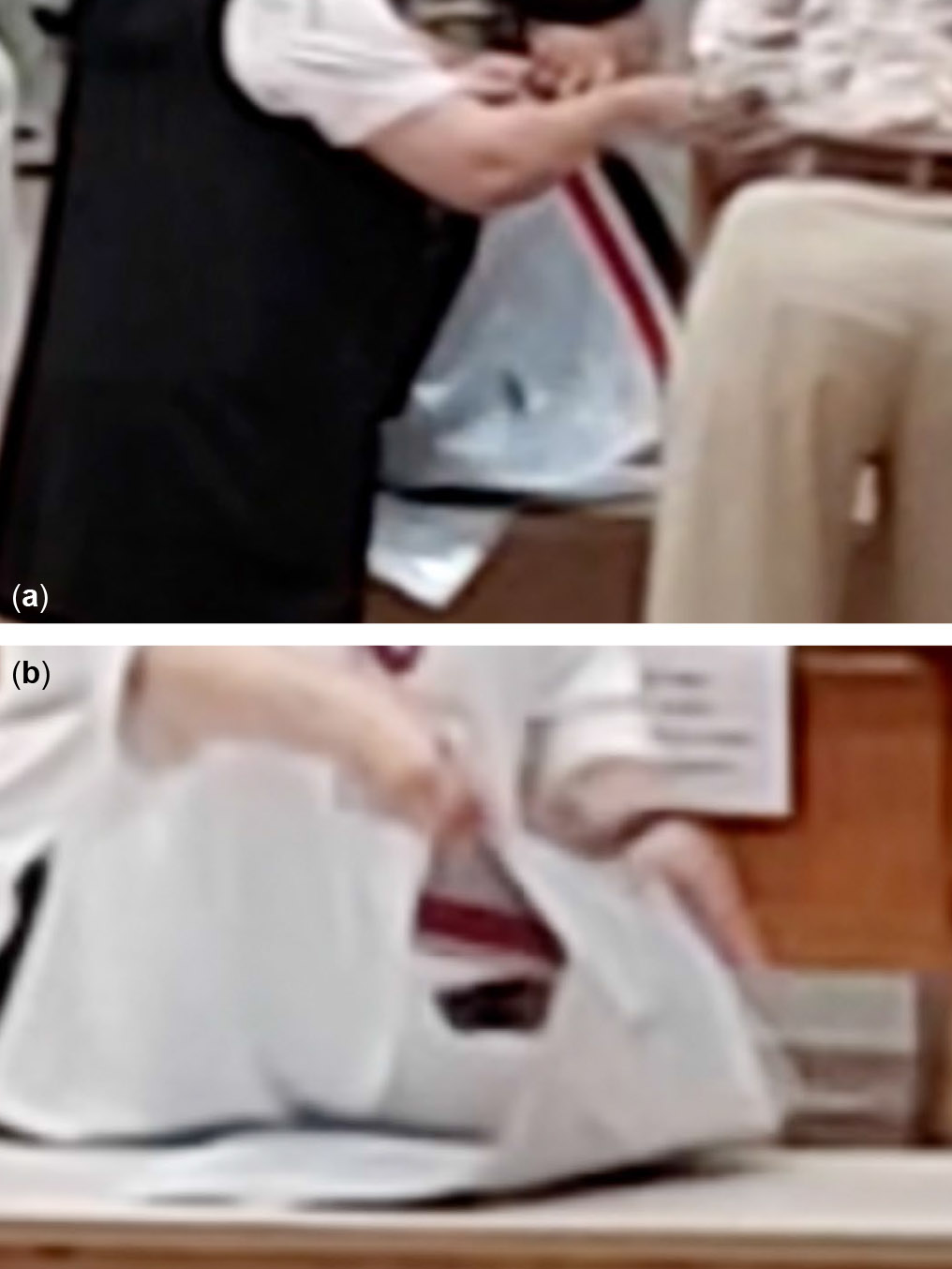

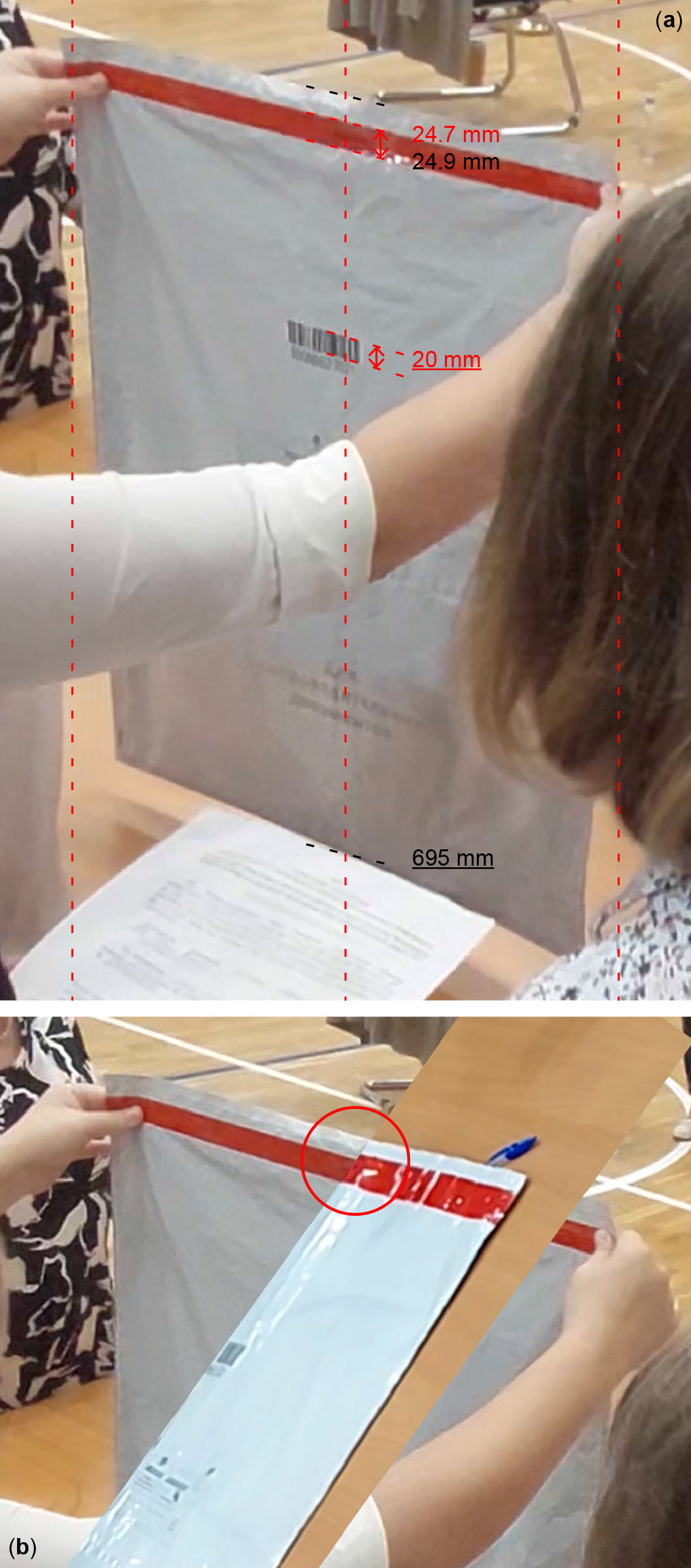

If the perpetrators have a duplicate security bag with an identical number, they can replace the original bag with it at night. The only difficulty would be forging signatures that may have been left on the original bag by observers and election officials, and reproducing any imperfections in the tape placement and the partial removal of the control stubs. These imperfections at precinct 219 revealed this entire fraud scheme (appendix D1).

3. Replacing one security tape with another

To avoid forging signatures, the perpetrators may choose to replace only the tape with its factory duplicate, instead of swapping the entire bag. At night, they would peel off the original security tape from the bag containing ballots, wash the bag with the solvent, replace the ballots, cut off the tape from the duplicate bag, and install it on the original bag. If any signatures cross the tape, they would still have to be forged or left incomplete, which may be noticed. Also the tape width is reduced. This is what was likely done at most of our precincts, see appendix D2 and thereon.

We note that there seems to be no technical reason why both tapes could not be made the same narrow width. For that, the bag would have to be prepared in advance by cutting off and reinstalling the original tape before it is presented publicly for the first time. However, this would increase the chance that the fraud is detected early.

At room temperature, a fully adhered tape has to be peeled off carefully and slowly to preclude the risk of stretching and tearing the bag material, as shown in fig. 6e. Strong cooling by spraying the content of an inverted duster can on the tape allows faster removal. In either case, it then takes about 10 minutes to wash the adhesive off the bag with solvent.

4. Reducing tape adhesion

Coating the bag with a thin transparent silicone layer lowers the tape's adhesion to the point that the bag becomes resealable without a trace [27]. While this method has been practiced at many polling stations in 2024 [9; 27], it has not been employed in Vlasikha. We remark that hiding traces of the backdoor is possible by removing the silicone layer with solvent before resealing the bag [27].

5. Inconspicuous slit

The easiest way to access the content of the bag is to cut a carefully placed slit in it. The slit is then taped over or heat-sealed [51]. Such a slit can always be detected by a meticulous visual inspection of the bag, which includes turning it inside out (after the contents have been removed) and examining its inner surfaces. Unfortunately, Russian election commissions often interfere with attempts to fully inspect the bag and its parts [27]. The slit may be deliberately covered with a paper document (such as a sealing certificate) placed in the outer document pouch of the bag [28]. Alternatively, the slit may be made virtually invisible from the outside by cutting it along a line of printed graphics, seam, or the security tape's edge. It is then closed with a transparent adhesive tape applied at the inner surface and is only readily visible from the inside.

Although this method is widely known, it was not employed in Vlasikha.

Appendix D: Forensic evidence of bag and tape replacements

The only remaining evidence consists of photographic images and video recordings made during the voting days. The observers and candidates did not personally seize any physical evidence. Instead, they filed crime reports with the local police and Investigative Committee requesting them to seize relevant items for inspection, as well as asked the judges in related lawsuits to subpoena the physical evidence. All these requests were ignored or declined. All physical evidence has since been confirmed destroyed.

The photographs and video recordings discussed below were taken by more that 15 people and 20 cameras (mostly those in smartphones). To keep our argument clear, we employ strictly uniform image transformations throughout this paper, such as rotation and (in collages only) scaling along one of the dimensions. Colour reproduction of objects varies with lighting conditions and camera used. The original camera files, along with the exact time and location of each recording, were included in the crime reports and lawsuits filed.

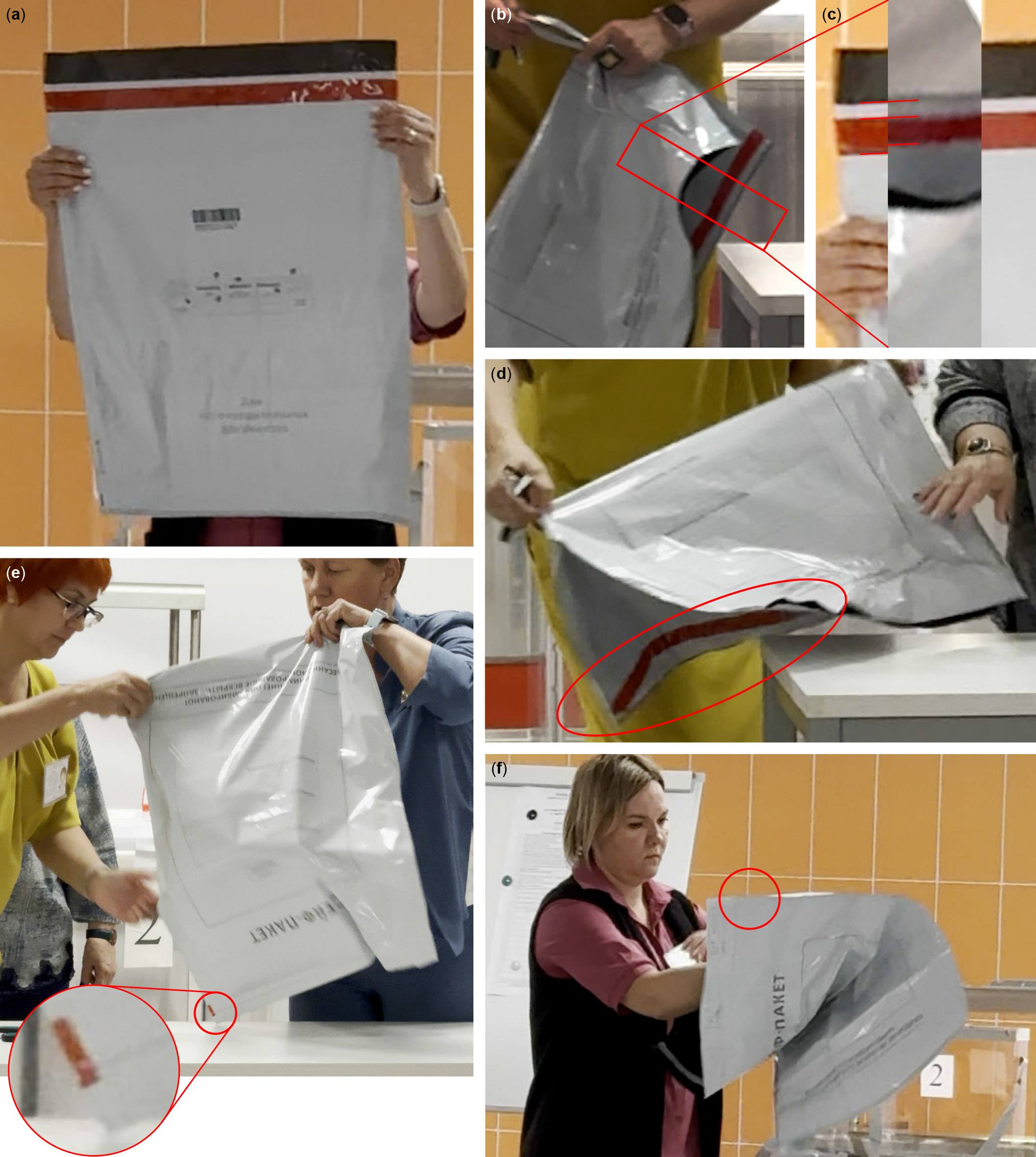

1. Factory-made duplicate bag at precinct 219

At this precinct, the first bag was swapped for its factory-made duplicate during the first night. High-resolution photographs taken before and after the swap show several features on both bags that lead us to this conclusion (fig. 13). First, the serial number and barcode printed on the bag are identical (fig. 14); the barcode decodes correctly. The barcode shows a prominent dead-pixel line (and another fainter one) running across it, which serves as a fingerprint of the machine and indicates the approximate date on which the bags were manufactured. The thermal transfer printer that prints this number and barcode is inside the machine that assembles the bag. Dead pixels producing white lines in this printer are common, their number increases from none to numerous in random places as the printing head ages. We have found images of barcodes of 5 other bags from the same batch [2], used all over Moscow Region in September 2021 elections. All of them show either a similar single white line or both lines (depending on the image resolution). Thus, the entire production batch [2], as well as our duplicate bags were made on the same machine.

Fig. 13. Photographs of two duplicate bags with identical numbers at precinct 219. (a) and (b) Photographs of bag A taken by an observer on 6 Sep 2024 after ballots were sealed in it. (c) Bag B on 7 Sep 2024 while it was retrieved from the safe for inspection. (d) Bag B on 8 Sep 2024 before it was opened at the vote tallying. Multiple differences prove that not only were pen signatures forged (2B) over a new security tape (3B), but the entire bag A was swapped while in storage on the night of Sep 6 for its nearly identical factory-made duplicate B bearing the same serial number and complete with the security tape.

Fig. 14. Barcodes on both bags were printed by the same thermal transfer printer, as evidenced by the same position of a prominent dead-pixel white line. (a)~Bag A. (b)~Bag B. The second faint line is not visible owing to a lower resolution of the latter image.

Despite having the same number and graphic design, these are different bags. A line of perforations that separates the control stubs from the bag punches through a single sheet of material in one bag but through both sheets in the other (fig. 15). The second leftmost control stub is partially torn off along this line on 6 Sep (see feature 5A in fig. 13 и 15), yet is unseparated in the duplicate bag on the later dates (see feature 5B). We also have a video recording of the duplicate bag at the vote tallying, where it is extensively handled for several minutes displaying both sides to the camera, showing no partial separation of this control stub. Line art printed on the bags shows a different amount of ink bleed (fig. 16). The small print at the bag's edge is further away from the edge on the duplicate bag (fig. 17). These are all common sample-to-sample variations distinguishing the bags.

Fig. 15. A line of perforation (marked with arrows) separates the bag from its detachable control stubs. (a) In bag A, the perforation punches through a single sheet of material on which the stubs are printed. Their black side faces the camera. (b) and (c) In bag B, the perforation punches through both sheets of material, which is not an uncommon sample-to-sample variation. Only the top sheet is visible in the images, but the same perforation also pierces the bottom sheet, on which the stubs are printed.

Fig. 16. Moderate (a) ink bleed during line printing preserves the lines on bag A as dotted, whereas stronger (b) bleed on bag B turns the dotted lines into solid ones. The arrow indicates the only gap between regularly spaced dots that remains unfilled with ink on bag B, confirming that the solid lines in image (b) are in focus and were captured accurately.

Fig. 17. Position of the small print relative to the bag edge and the seam in (a) bag A and (b) bag B. (c) A collage shows the small print to be at a different distance from the edge on the two bags. In the collage, the image of bag B, taken by the camera at an oblique angle, is uniformly stretched vertically to match that of bag A.

As expected, handwritten signatures on the bags are also distinct (fig. 18). The second set of signatures had been forged, according to reports by observer Ushakov and candidate Razina who both signed the bag on 6 Sep. The tapes themselves are stuck fast in different positions with different creases. Nevertheless, both are genuine, untampered security tapes, as evidenced by the presence of faintly visible honeycomb pattern with words STOP СТОП and their correct (30 millimeters) width (fig. 19). The scuff mark (8B) on the second tape suggests it came attached to the bag and was sealed normally.

Fig. 18. Signatures of observer Ushakov and candidate Bulkina (who superimposed her signature over his) are (a) original on bag A, according to Ushakov's report, and (b) forged on bag B. Several other signatures are also forged.

Fig. 19. Photographs of the tapes sealing duplicate bags at precinct 219 processed to maximise contrast. Contrast is maximised individually in each primary colour channel (red, green, and blue) using a curves tool, applied uniformly over the entire image. The image resolution is then reduced using bicubic interpolation with some sharpening, to further bring out subtle patterns. (a) Bag A. (b) Bag B. The honeycomb pattern visible on the tapes should be compared with fig. 6a,b и 7; its presence here confirms both bags have genuine factory security tapes. For those having difficulty spotting the honeycomb pattern, it is outlined in (c). The size of the visible hexagons also confirms both tapes are about 30 millimeters wide. The presence of scuff marks (8B) about 5 millimeters from the tape's bottom edge indicates a normal sealing procedure, with the liner being removed slightly incorrectly (pulled from under the tape as shown in fig. 7 instead of bending the tape over for easy liner removal as recommended by the manufacturer and shown in fig. 6(b). This slightly tears the adhesive along this line. These marks are typical in normal use, because many people intuitively remove the liner this way instead of reading factory instructions.